Down and out in Bogotá

This first appeared in The Bogotá Post in 2017. It tells the story of some of the capital’s large population of street people.

Bogotá’s street dwellers are known locally as mendigos, pordioseros or ñeros, (which I guess is a short for limnosero, or ‘beggar’) or los desechables, ´the disposables’, which sums up their status in most citizen’s minds. Officially they inhabit ‘Estrata Zero’ – social strata zero -which I thought was a joke until I saw it written on an official document.

Officially the city hosts 9,600 CHCs, based on a census from 2011, but that is probably a massive underestimate, says an official at the local mayor´s office tasked with assisting them: ‘We know there is a lot more but exactly how many…who knows?’

The local authorities call them ‘CHC’, Ciudadanos Habitantes de Calle, and further split them into ‘en la calle’ (people who make their living on the street but sleep in dosshouses) and ‘de la calle’ (those shivering under a thin blanket overnight on the street). This is a fluid division since many street dwellers live in flux as their fortunes wax and wane, some days getting lucky and enough coins to pay for a hostel bed, other nights blowing it on a 2000-peso twist of basuco – low-grade coca paste, a residue of cocaine labs – and ending up in the rain again.

Clearly it is not easy to count a constantly shifting population that in general rejects authority and has mastered the art of disappearing in plain sight, and with less than 5% living under any kind of institutional care. Some street dwellers themselves estimate the true figure to be around 40,000, but there is no hard data. Everyone agrees it is many more than 10,000.

The same census gives the two main reasons for living rough as ´family violence´ (44%) and ‘consumption of psychoactive substances’ (34%), and reports that 90% are male and nine out of ten are substance addicted. Third on the list is ‘contextual aspects of the country´, which put plainly is the Colombia’s decades of civil strife, with 6 million Colombians registered as displaced (equal to Syria and Sudan) with a high percentage psychological problems; one study of families forcibly displaced showed 100% suffered long-term post-traumatic stress.

In Bogotá people fleeing violence can become anonymous.

So behind the scenes of Bogotá’s homeless is a much bigger picture of tens of thousands of families uprooted from all over Colombia and shifting, frequently to Bogotá, a city seen as the most tolerant for displaced, with more chances to make a living, and with less risk of the ‘social cleansing’ by death squads – the killing of people on the margins, known as fumigacion – that has plagued Colombian cities for many decades. As one street-dweller told me: ´Here I can be anonymous’.

Some have had to flee for their lives to the city to escape massacres or death sentences imposed by paramilitary groups linked to the state; with these memories they approach the local authorities with caution and are too spooked to register for assistance, particularly given the jobs-worth approach by most city officials that requires filling in every small detail of your life, address, birth data, even where you were baptised, even before you get inside the door. So while the politicos play out the peace process on the world’s stage, forgotten victims of the conflict are shuffling through the shadows recycling our rubbish.

All these thoughts are rattling around my head when I set out to talk to some street dwellers. I don’t have to look far. Several interviews are done literally on my doorstep, and one in my kitchen. These are people I realise I know and see nearly every day, maybe throwing a coin from time to time, or a bag of old clothes on a cold night but never thinking of who they are or where they come from, never stopping to ask their name.

Descent into vice

So actually conversing is something of a revelation. Everyone has a different story on ‘falling into vice’, often told with humour and self-reflection, without self-pity. But it must be said my quest is filtered towards people able to understand my request for information, and aware that their comments will be published, which means those habitantes en calle that are in a more stable stage and are on the rebound, so to speak, or at least in a moment of lucidity. It is difficult from a practical perspective, and morally dubious, to interview a glue sniffer semi-conscious in the gutter.

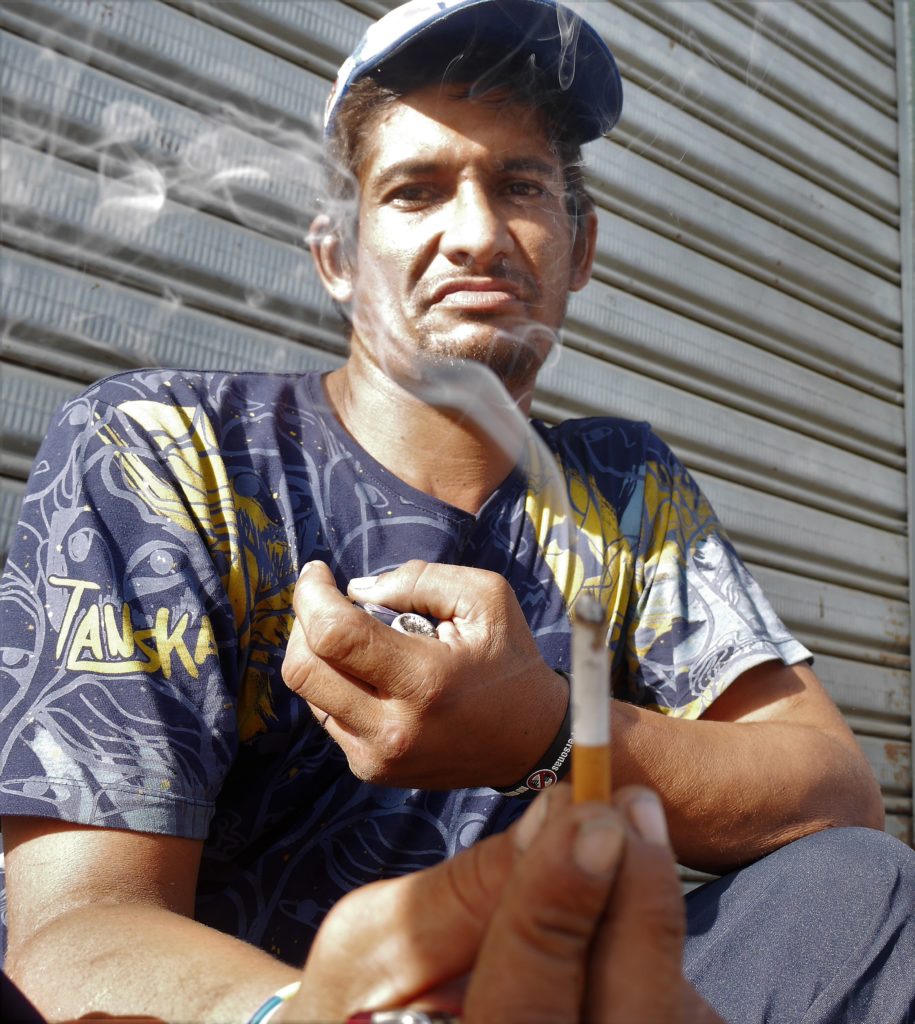

Life on the streets usually comes in stages of descent from hard drinking, often adulterated alcohol called chirrinchi, to smoking marijuana and basuco (done by pistoleros) to smoking the coca paste in pipes (done by piperos) or sniffing glue, (a brand called Boxer). After you hit rock bottom, if you survive, you may bounce back, and then fall back again, a cyclical process that might depend on your own will-power or outside help.

This help can come in the form of ambulatory and local hospital-based detox programs, including internships, overnight shelters and back-to-work schemes, and psychosocial support. According to the mayor’s office, this is a holistic approach that sets out to tackle drug addiction as a health and social issue. But with so many street people, of which 93% are substance-addicted, these resources only stretch to a minority.

‘It’s a hugely complex response to a massively complex problem,’ an outreach worker tells me. One problem, he points out, is that many CHC avoid help, and a Colombian law passed in 2015 to protect CHC’s rights also prevents the state from forcing them into treatment programs. In fact the police are officially prevented from obstructing or moving any street person from their chosen site, a regulation that has infuriated shop and business owners in areas where street people congregate, namely central zones such as Santa Fe and Los Martires.

These frustrations boiled over last year after the city mayor send police and army into the Bronx, Bogotá’s largest downtown olla (literally ´cooking pot’ but figuratively ‘vice den’), which consists of a few streets inhabited by drug gangs and every imaginable vice and violence. The massive operation mysteriously failed to catch any major kingpins (the rumours are that corrupt cops tipped them off) but did manage to scatter street folk and drug dealers into nearby business sectors

‘Let’s hope the social response is as clean and efficient as the military operations’, said one media commentator, though of course it wasn´t. In fact, not one social services department was briefed to prepare for the outcome. The impasse with local businesses lead to some politicians to predict a return to the dreaded fumigaciones of recent decades.

The question arises: where do all the drugs come from? The answer is a 6,000 billion-peso local drug market pushing low-grade cocaine residue to school-kids to secure future business. At the top of this pyramid of misery are the same drug capos that export refined cocaine overseas. So just like with coffee there are ‘domestic’ and ‘export’ grades of the coca product. Ironically, it is the disruption of cartel export routes that has led to large quantities of the low-grade drugs flooding home markets. And the soft target for these peddlers is the vulnerable street people, at the bottom of the pyramid collecting the coins to feed the giant monster above.

A dangerous life on the streets

Street people are also the targets for violence. While most well-heeled rolos live in fear of beggars, it is the street people themselves most attacked, robbed and murdered. More than half report serious injuries, such as stabbings, 60% have been robbed, more than 75% beaten (usually by the police) and a third forced off their land. And in Bogotá the homicide rate for street people is at least 15 times the city average. Of course one must add that a quarter of these crimes are by other street people, and there is clearly lack of trust within the community (if you can even call it that) of Estrato 0.

Should we automatically see Estrato 0 as victims? Some commentators suggest that street life can be an alternative, interesting and fulfilling existence. True, most people I talk are in good humour and have pride in many aspects of their lives, and one detects a certain machismo in sleeping out, dodging the authorities and avoiding the help programs.

But dig a bit deeper and everyone is looking for a way up and out. What tears most is losing contact with friends and family, living without knowing where children or grandchildren are (or even knowing if they exist). Get clean, get work, get back to the family, is a common mantra. But invisible barriers, the tentacles of addiction or mental health problems, hold them back.

Is there some hidden upside to life on the streets, maybe some sense of freedom that harks back to mankind’s nomadic soul? I throw the question out. One laughs: ´Yes, I live free on the streets. But slave to the drugs.’

In their own words….

Some stories of life on the streets in Bogotá

Gabriel, 76 years old, from Arauca. Displaced by the conflict. Came to Bogotá after a massacre in 2004 and has lived on the streets ever since.

‘I worked on farms when the paramilitaries came, they told us to leave or die. But we stayed, we did not want to lose out jobs. They came back and burned houses and killed some 15 people.’

´Some of us escaped by river, swimming. I had to leave everything behind. We found a truck to take us to Villavicencio, but were not safe there so I took another truck to Bogotá. I have never been back to Arauca.´

´The first month in Bogotá was tough. I did not know how to survive or where to go. There was no-one to help me. But after some time I had learned the code of conduct of life on the streets, where to go and how to ask for money.´

´I lost contact with my friends and family. I have two daughters, and some grandchildren, but we lost contact many years ago. I have no resources to find them. Now I am alone.´

‘There is not much friendship among the street people. The poor rob the poor. There are many bad people so I work alone trying to get money and food. Better alone than in bad company, I say. I need to get enough cash every day – at least 6,000 pesos – to pay for the hostel where I can stay the night, in a room just big enough to lie down.’

‘I read newspapers at night. The country is changing but will be difficult to heal. I sometimes talk to truck drivers from Arauca to see how things are there. My hope is one day to go home, but how to get the money? It´s a struggle.´

Wilmer, 25 years old, from Bogotá, has lived on the city’s streets since he was a child

‘My parents died in an accident when I was ten, and I had no other family to care for me so I lived on the streets.’

‘I sell sweets to try and earn around 15,000 pesos a day, to pay for a hostel bed and food. If I can’t get the money I sleep on the streets, on a piece of cardboard.´

‘I am walking the streets usually from 6am to 9pm to get the cash. Sundays are the worst days – less people around so less money for the hostel. Last Sunday I had to sleep out.’

‘The worst thing sleeping on the streets is the cold. Also the police wake us up and move us on. Sometimes we get a good beating.’

‘Last year I was attacked and stabbed, bleeding everywhere, but this time the police helped me and took me to hospital.’

‘Sometimes I work, I can do some construction work, but I have not been able to do this for two years. I would like to go back to work.’

‘Nowadays companies ask for photos and documents, a CV and a medical exam, but these cost money. I spend all the money I earn on food and the hostel, there is nothing left over for other things. ´

Carlos, 55 years old, is originally from a Bari Motilón indigenous community in a remote part of Norte de Santander. He carries an oxygen bottle after a stab wound to the lung.

‘When I was 8 years old the ELN guerrillas told my family I was to be prepared for life a guerrilla. They were coming to take me. So I had to flee, at night, in the back of a truck to Cucuta then on to Cali where I lived on streets.’

‘I never went to college. But I learned the life of the streets, and in jail, where I was always sent because at this time I was a thug, robbing and attacking people´

´Then around 30 years ago I had to flee to Bogotá. Cali was too dangerous with the social cleaning, the fumigaciones, street people were being killed. In Bogotá it was safer and I could start again.´

´I was worked as a reciclador collecting scrap to sell, but one day four men attacked me for my bike. I did not let go so they stabbed my twice in the back, puncturing my lung.’

‘The damage was permanent so since then I have to use an oxygen bottle, and park cars on the street. The oxygen is paid for by the government, and most of the medicines I need, since I have the Carta de las Habitantes de la Calle (Street Dweller Letter). I am officially Estrato Zero.’

Didier, 38 years old, and Marcela, 28 years old. They met living on the streets of Bogota. Didier is an electronics engineer originally from Santa Marta.

(Didier) ‘I had an electronics workshop in Santa Marta, but the local paramilitaries demanded money, in the end I couldn’t pay so they were going to kill me. So around 15 years ago I came to Bogotá.’

‘I lost my self-control and fell into vice and drugs, which lead to conflicts with my family. Drugs are like a knife at your throat. I just wanted to leave the system, and ended up on the streets.’

(Marcela) ‘I was raised in Matatigres in Bogotá, but left home at 13, after problems with the family. Since then I have been on the streets. I met Didier two years ago.´

(Didier) ´We get good health care, even with no documents, the hospital attends us. But it harder for women on the streets, and once they get addicted they have to sell themselves to get money for their drug habit, it is more dangerous for them and more health risks.’

´The authourities send min-buses at night to collect us, living on the street, and take us to the shelters. There you can get a bed with blankets and food, sometimes work, but I prefer to stay on the streets. We sleep every night on the street, usually on the same corner.´

William, 55, originally from Ibague, Tolima. His life was first disrupted when, at age 8 years old, his father threw him and his mother out of the house.

‘In Bogotá I worked in construction but the bosses never paid us, so I ended up broke and fell into vice, taking basuco. Now I´ve been many years on the streets, usually sleeping out, sometimes in hostels. Lately I have been sleeping out in the cold. Last month the police came and took all my blankets, it was raining, they threw my blankets in the back of a rubish truck.´

‘I used to visit the Bronx, and Cartucho before it was knocked down, to get drugs. It is good they also cleared the Bronx, it was a terrible place where gangs fed people to dogs or dissolved them in acid. These are not rumours, the stories are real. I know.´

‘I have been three times in jail, once for six months for the neglect of my children. I couldn´t feed them, I had no work and no money. So they sent me to jail. My kids are grown up now, but I have lost touch with them since five years ago. It´s sad I can´t see them. ‘

‘Some days I recycle rubbish to get money. I work alone, you can’t trust other people on the streets, some will stab you for money. But I do have friends and we meet up, every few weeks. Then I fall back into the vice again, sometimes for a week.`

`I know street people who have found a job, got married. They have a life. There are programs for street people to get off the drugs, but these are internships, which I don´t like. I rather live my own live, and with God’s help will get off the drugs and find work.´

Mauricio, ‘El Gato’, 50 years old and from Bogotá, was a heavy user of basuco (cocaine residue) and slept rough for many years but has since gone through a treatment program.

‘I got into drugs through curiosity, to see the effects, and started as a pistolero, smoking basuco in cigarretes, which is OK, the effects are not so strong, but then became a pipero, using a pipe.’

‘With the pipe you neutralize hunger, and can go five days without sleeping, but your condition deteriorates very fast. You a fearless. The piperos are the guys you see stepping off the pavement into fast traffic, they don´t care.’

‘But you can make more money begging as a pipero, you smell so bad and your clothes are so ragged that shops and restaurante throw money at you to move on.’

‘Sleeping rough is dangerous. One night I slept in front of a garage and a car nearly ran me over. Some people get killed, stabbed, maybe by other street people. In Bogotá the most dangerous places for street people are the poorer outlying barrios, that’s where they die fastest. That´s why many prefer the city centre to stay safer.’

‘There are often conflict between gomelos, the glue sniffers, and the piperos, and many people carry knives. I never back down from a fight, even if they have knives. You have to stand your ground.’

´I got off the drugs through an intern program run by social services. I was an intern for six months, in a large center with good facilties, we got clothes, bedding, food but had to do many workshops. I ended up as a voluntary outreach worker at the Hospital Santa Clara, helping other addicts. Now I park cars in the street and stay in a hostel most nights’

‘But I am still vulnerable, and have severe withdrawl symptoms, such as fever and anxiety. I refuse to take the pills from the hospital to treat this, they turn you into a zombie. I prefer to live real.’

‘From time to time I fall back into vice, but only drinking chirrinchi, cheap liquor, it’s only 2,000 pesos for a bottle. But I never drink around my kids, I want to be a good example.’