1538: Bogotá’s conquest

This story first appeared in The Bogotá Post in August 2018.

Were Conquistadors a Good Thing or a Bad Thing? I’m in two minds. True, those bad-boy gold-hungry Spaniards rained down hell on the locals using sharp Toledo swords, armoured horses and mastiff dogs trained to munch testicles (that’s a historical fact, not some corner of my twisted imagination).

But the pre-Colombians weren’t living in paradise either: the continent had head-chopping Aztecs who sacrificed 80,000 folk in just four days to inaugurate one pyramid. The Maya had similar bloody death cults, while further south the humourless Incas founded an empire nominally on trade but backed by ruthless might. Any detractors were killed along with family, friends, pets, plants and the back garden sprinkled with salt.

With these thoughts mind I cycle downtown to confront Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, pre-Colombian Colombia’s chief invader and Bogotá’s founder. I find him po-faced on a plinth in the pretty Plazoleta del Rosario, looking remarkably unlike any of his portraits (I wonder if the Spanish government have a warehouse of idealised conquistador statues to give away to former colonies) and holding a sword above his head to form a cross.

Now here’s a mixed message: a sword as a cross. Convert or be killed. Jiménez would have known all about that, coming from a Spanish Jewish family (originally from Morocco) forced to adopt Catholicism but suspected of secretly observing their Judaic beliefs. Intriguingly, he named his first settlement on the banks of the Magdalena River ‘La Torá’: the Torah.

Whatever his inner faith, the young lawyer-soldier would need to draw on every ounce of it soon after leaving the coastal colony of Santa Marta at the head of 800 armed Spaniards with horses and thousands of indigenous slaves from coastal tribes.

The year was 1536. The plan was to march up the banks of Rio Magdalena, with support from a small flotilla of boats, in search of wealthy civilisations to raid, maybe even reaching Peru – from where fabulous wealth was being reported – or some rumoured ‘El Dorado’.

Instead they found swamps, jungles and a maze of flooded plains where hidden tribes would pick off the invaders with poison arrows and darts. Even nature conspired against them. Rain, mud, mosquitoes, took their toll. Boats sank on the treacherous river, only for the survivors to swim ashore and die in a hail of arrows. Or to be chomped by caimans. Or sink in quicksand.

At night the terrified chapetones – wannabe Conquistadors – were dragged from their hammocks and eaten by jaguars, bitten by poisonous snakes or struck by tropical diseases., They were even mauled by anteaters.

Eight months in, and three quarters of the Spanish contingent – and untold numbers of slaves – were dead or missing. Clearly a Bad Thing. The survivors faced starvation and endless lagoons with no clear path to the highlands. The SNAFU was now FUBAR. Most people would have given up. But not Jiménez. He pushed on.

This surprising decision was based on salt. The commodity had been getting scarcer as they travelled from the sea, but suddenly natives were seen trading blocks of rock salt from an inland source. Following this salt trail, in 1537 Jiménez and his survivors (now a straggle of 200 semi-naked Spaniards with slaves) struggled up the Andean slopes into fertile temperate plains and the Muisca realm.

At this time the Muisca were one of four Bronze Age civilisations in the New World (along with Incas, Mayas and Aztecs), but the ones you never read about at school. Perhaps they just weren’t bloodthirsty enough.

This is because they had formed a mostly peaceful confederation of tribes sharing common language and religion, occasionally unifying large mutual armies to fight off aggressors (usually lowland tribes), but generally preferring a harmonic existence based around sun and moon worship (human sacrifices were rare) and high-class jewellery, pottery and textiles. They were also excellent farmers and had salt mines and a huge supply of emeralds from eastern Boyacá. These they traded for gold and cotton.

What happened next is subject to some historical debate, but in most texts (and certainly official Colombian sources) it is seen as a Good Thing, with Jiménez portrayed as ‘the benign Conquistador’ who vanquished the Muisca with ‘reason, rather than the sword’ and ‘minimum bloodshed’.

This theory only holds if you are daft enough to believe in some divine right of the beardy Christians to plunder and harvest souls. Nowadays most people don’t. But back in the 1500s opting out of religion was not a safe choice for a European, or probably a Muisca. Thus a clash of cultures was inevitable.

And considering their devastating journey across the lowlands, the Conquistadors were now in serious need of anger management. Add to this the fact that these young adventurers (average age, early 20s, Jiménez himself only 27) were sent mostly to their doom under a ‘conquisting’ franchise model that was broken and morally bankrupt in the first place.

The Spanish crown would grant concessions to explore, govern, plunder and convert the New World risking little of its own money, meanwhile demanding 20% – the ´royal fifth’ of all treasure. This forced those doing the dirty work – the Conquistadors – to constantly loot to pay back the expedition costs such as boats, soldiers, horses, priests, then the royal taxes, then the share for each participant, with a slim chance of profit.

And get this: any Conquistador arriving in the New World had a 30% chance of dying in his first year – worse odds than Russian roulette. This attracted all manner of desperados with nothing left to lose. Jiménez himself was escaping the shame of a fumbled family law case.

Still, from the Muisca perspective, none of the above justifies what really a Bad Thing as the arrivistes roamed the eastern highlands on a two-year looting spree torturing and killing caciques, zipas, zaques and iracas (the Muisca’s regional leaders) to get at the gold and emeralds.

Of course, the Muisca warriors – the Guechas – organised and put up some token resistance (first at the salt mines of Nemocón) but were hampered by their poor weapons and a strange habit of going to into combat with the mummy of a dead ancestor strapped on their back.

Meanwhile the Spanish employed their usual chicanery to divide the locals by making false promises then forming (and breaking) alliances. Tisquesusa, the powerful, the Zipa of Bogotá fled from the advancing force, evacuating his main town but was soon stabbed in a skirmish near Facatativá.

Back up north in Hunza (now Tunja) the Zaque was tortured to death, and his successor decapitated. Meanwhile the main Sun Temple at Sugumoxi (now Sogamoso) was stripped of gold and burned. In a later battle 4,000 Guechas were killed in and their leader Tundama (from the town of Duitama) killed with a hammer.

Then there was the betrayal of Sagipa, successor to the murdered Bogotá, who initially aided the Spanish but was then tried and tortured to reveal hidden treasure. He died after being coated in boiling fat. Jiménez later justified this by claiming that Sagipa was ‘anyway a bit infirm’. Ho hum. Such violent acts were symptomatic of gold fever. However much they got, the Conquistadors wanted more, and more was never enough.

But maybe there was not that much in the first place. The Muisca traded for gold, and what little they had was beaten into paper-thin alloys sheets to make fine art and decoration. Once stolen by the Spanish and melted into solid coinage – note that peso means both ‘currency’ and ‘weight’ – it didn’t weigh much.

And under torture the locals would exaggerate the massive riches that could be found ‘just over the next horizon’ in the hope the Conquistadors would head there. And the feverish Spanish – who hardly took ‘no’ for an answer – were happy to latch onto any hint of El Dorado, which they mistook for a lost city (while all along it was a person sprinkled in gold dust in jumping in nearby Guatavita lagoon).

And what about Jiménez? In 1539 he sailed to Spain to claim governorship of his Kingdom of New Granada. Instead he found himself on trial. This was a common tactic of the Spanish Crown: encourage the Conquistadors to commit excesses, then strip them of their wealth and titles through legal traps.

Again, Jiménez fought on. Using his own resources (he’d probably hidden some Muisca emeralds in his socks) he won the cases and a decade later returned to the Andean highlands and Santa Fe de Bogotá, the settlement he had founded in 1538. The city celebrates the anniversary of this event each August.

But in time Jiménez himself has become largely forgotten, which for a Spanish nobleman is definitely a Bad Thing. Despite his travails he never made it into the Conquistador hall of fame like Hernan Cortes and the notorious Pizzaro brothers.

After some more disastrous – and financially ruinous – expeditions to find El Dorado in the Llanos, the worn out old soldier-lawyer retired to Suesca to write his memoirs. Which were then lost. He died poor, of leprosy, in 1579. Hence Colombia’s conquest was swept under the carpet of history, a mere foot-note to the chronicled invasions of Mexico and Peru. For most rolos, Jiménez is now just a Transmi station, and a nasty one at that.

And by a twist of fate the vanquished Zipa is enshrined as Colombia’s capital. After all, Bogotá was a Muisca settlement long before the Spanish rode up and will be remembered as such long after Jiménez’s statue slips into storage. That probably is a Good Thing

Further Reading

Invading Colombia: Spanish Accounts of the Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada Expedition of Conquest, edited by J. Michael Francis. English translations and notes from rediscovered first-hand accounts to the Colombian conquest.

Historia de Colombia y sus Oligarquías, by Antonio Caballero. In Spanish. A fun look at local history with cartoons. You can find on-line versions, check out Capitulo 2, En busca de El Dorado

What’s in a (place) name?

Newcomers to Colombia’s eastern Andes are often surprised by the not-very-Spanish-sounding towns. It took me years to get my tongue around Fusagasugá and Chiquinquirá, before realising these derived from pre-colonial Chibcha languages, such a Muysccuban which was spoken by the Muiscas.

Technically these are extinct languages since they are no longer spoken day-to-day. But many words live on in the rich lexicon of slang spoken by many Colombians (see related article in this edition on ‘Cachaquismos’), and in the place names of Cundinamarca and Boyacá. Here are some Muisca toponyms.

Bogotá – corral outside the fields

Chia – the moon goddess

Ciénega – place of water

Choachi – mountain of the moon

Facatativá – stronghold on the plains

Fúquene – den of the fox

Iza – place of healing

Pachavita – proud chief

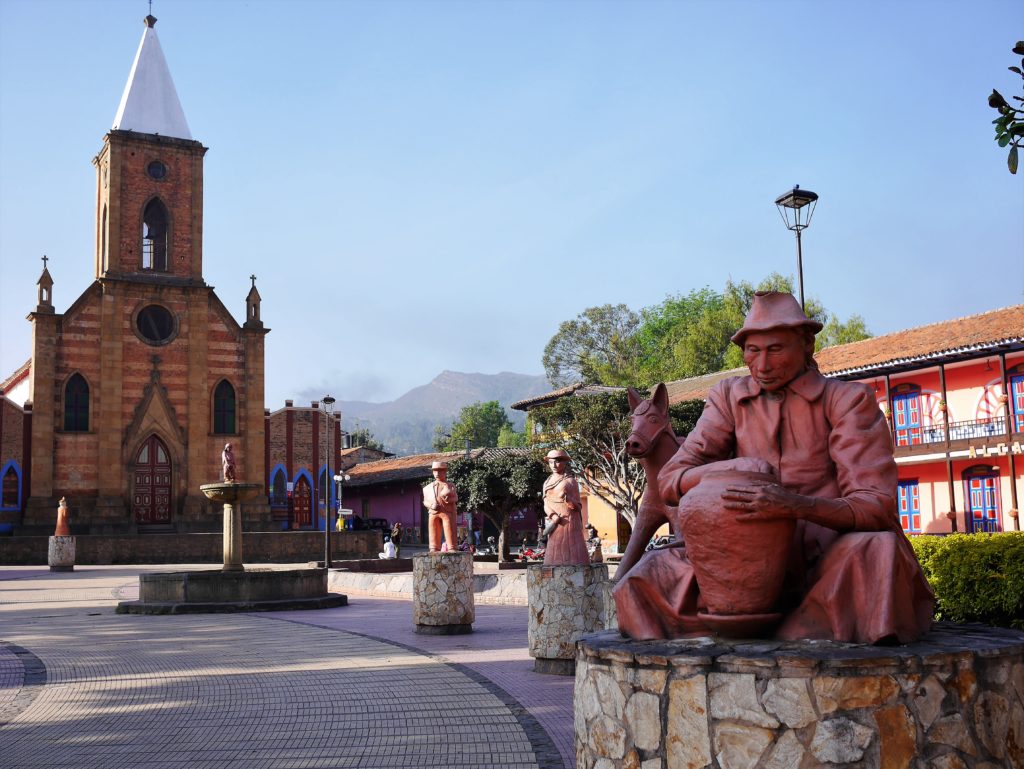

Ráquira – village of the pans

Suba – flower of the sun

Zetaquira – land of the snake

Meet the Muiscas

Muisca culture lives on beyond just place names. Here are places you can get a glimpse of their past.

Laguna de Guatavita – the mysterious green lagoon and sacred Muisca site, also the origin of the El Dorado legends, is a major tourist attraction which includes a visit to a bohio and talks on Muisca culture. The lagoon is 75kms northeast of Bogotá and can be booked a day trip from the city.

Museo de Oro – Bogotá’s gold museum houses a large collection of Muisca artefacts, including the famous gold Muisca Raft which depicts the ceremony of El Dorado.

Sugamuxi and the Temple of the Sun – this province in Boyacá calls itself the Cradle of the Muisca and encompasses the reconstructed Temple of the Sun (in the main town of Sogamoso), Muisca rock painting, and encounters with Muisca communities which offer spiritual retreats, music and food. Find more at www.visitsugamuxi.com

Parque Arqueológico de Monquirá– this astronomical observatory of standing stones and burial complex dates from nearly 2,000 years ago but was also used by the Muiscas, it is 5km from the Boyacá town of Villa de Leyva.

.