The Giant Sloth slaughter

by Steve Hide

A version of this story appeared in The City Paper in 2015.

In a quiet corner of Bogota, in the small museum of the Servicio Geológico de Colombia, a giant ground sloth rears high above the glass exhibition cases to claw a stumpy tree. The fossil figure frozen in time is sentinel to a remarkable chapter of South American prehistory.

Popularly we know these beasts from Sid the Sloth in the Ice Age movies, an amiable klutz fast-tracked for extinction. But ground sloths like the Eremotherium (to give the Bogota beast it its proper name) were no misfit. They roamed the New World for more than 20 million years munching vegetation until a catastrophic encounter with a small but smart and voraciously hungry biped: Homo Sapiens.

What followed next can be described as a great sloth slaughter, or more scientifically as the Great Quaternary Extinction. In an astonishingly short space of a few thousand years – a blink of an eye in geological terms – these giant beasts were eaten out of existence leaving only smaller cousins such as tree sloths and anteaters that survive today.

Latest scientific research supports the theory that stone-age human hunters using arrows and spears killed off these sloths soon after hominid migration to South America around 20,000 years ago. Along with giant sloths disappeared a host of fantastical megafauna; proto-horses (hippidion), two-tonne bears (arctotheria), rhinoceros-sized herbivores (toxodon), elephant-like gomphotheres and mastodons, and glyptodons, armadillos the size of a saloon cars.

Also under threat was smilodon populator, a sabre-tooth tiger that preyed on the same large herbivores the hunters were wiping out. At 400 kilos, with foot-long fangs, smilodon was the stuff of nightmares. Its exit from the ecosystem probably came as a huge relief to humans double-locking their cave doors at night.

The Overkill theory

Still, it does seem incredible that small bands of homo sapiens, hop-scotching down the South American coast and using stone tools, could really kill off so many large animals. Hence there is considerable scientific debate whether this extinction event was really caused by human overkill, or climate changes, shifts in vegetation cover, shrinking habitat or (you guessed it) asteroid strikes. Or maybe a combination of factors.

This is more than abstract conjecture. The idea that our ancestors munched their way through the megafauna menu without noticing the low larder is rather unsettling. Somehow it feels better to blame asteroids.

Unfortunately most evidence points to a bloody human hand in the demise of Eremotherium et al. A detailed scientific analysis published by the Royal Society in 2014 concluded that overkill was the ´primary driver´ of worldwide megafauna losses in the late Quaternary, particularly in South America where the extinction was most severe and with no evidence of asteroids or sudden climate change. Where vegetation changes did take place, dietary studies show that giant sloths could switch from eating grass to shrubs or trees to keep pace. What they could not cope with was the sudden arrival of new neighbours on the block: Mr and Mrs Sloth Slayer.

And a strange fact is that wild animals lack a flee response to humans until we start killing them over many generations. You can see this for yourself in remote islands like the Galapagos, where wildlife sits happily next to tourists, or Antarctica where you can literally pick up a penguin.

Migrating early humans arrived very late in the New World, then stormed it like kids in a candy shop, and within a few centuries had spread to its remotest corners. The plodding mega-fauna, naïve to wily human ways, never knew what hit.

South America suffered the biggest extinction event and lost a whopping 46 out of 58 genera of large mammals. Compare this to Africa, which lost just 2 out of 44. African animals such as elephants and giraffes had evolved alongside human-like species for millions of years, learned to sense and evade hunters, and hence survive to today. This is why Africa still has many beasts over 1,000 kgs, and elephants as heavy as 6 tonnes, whereas the largest South American land mammal, the tapir, is a lightweight 250 kgs.

But it even if slow and naive, South America´s giant sloths would be a formidable adversary. Their largest modern relative, the ant-eater, weighs just 40 kilos but can kill a human when cornered.

Even small tree sloths are tough critters as I found out picking one up from the middle of a busy road in southern Colombia. I lifted it carefully by the wiry fur on its nape but it could still twist its muscular torso and gouge my arms. Eventually I got this ingrate safely to the roadside jungle but not without some bloody scratches.

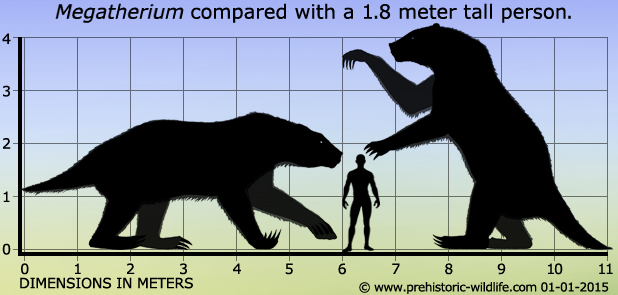

Imagine my rescued tree sloth scaled up a thousand times and you have megatherium, the largest known ground sloth at 5 tonnes and 7 metres long, with body armouring made of bony plates under the skin and long claws that could fend off sable tooth tigers. This is one sloth not to grab by the neck. Other mega-fauna like more agile mastodons, which are very similar to modern elephants with long tusks, would have been a bigger challenge.

The hunt is on

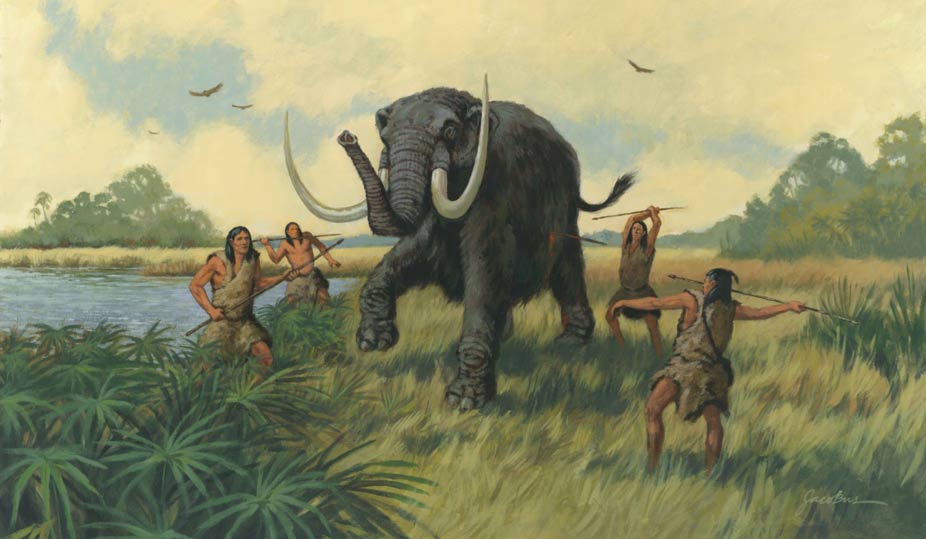

To take down these big beasts hunters would need team work and long-range weapons. Using evidence from digs, researchers have built up a picture ofstone-age hunters ambushing their prey with a barrage of stone-tipped spears and arrows designed to cause open wounds. One key weapon was the atlatl throwing spear, a simple but effective projectile. The hunters would track the bleeding animal until it was in a weakened state and finish it off.

Still, some experts question why our ancestors risked their lives to spear a giant sloth and leave the safer small game. One answer is that smaller animals with shorter life cycles evolved faster to evade humans, so were harder to spear. The other can be found on the front page of any modern-day fishing magazine: we like to go big. I can imagine after a long day´s hunt the Sloth Tag Team would sit around quaffing fermented berry juice and yarn about spearing that really big sloth, or the even-bigger-one-that-got away. Though in the end, none did get away.

Or did they? The exact end-date for giant sloths is unclear. While most scientific texts state they were all snuffed out by 10,000 years ago, it is a fact that smaller ground sloths were still roaming the Antilles Islands until just 4,000 years ago, shortly after humans arrived in canoes.

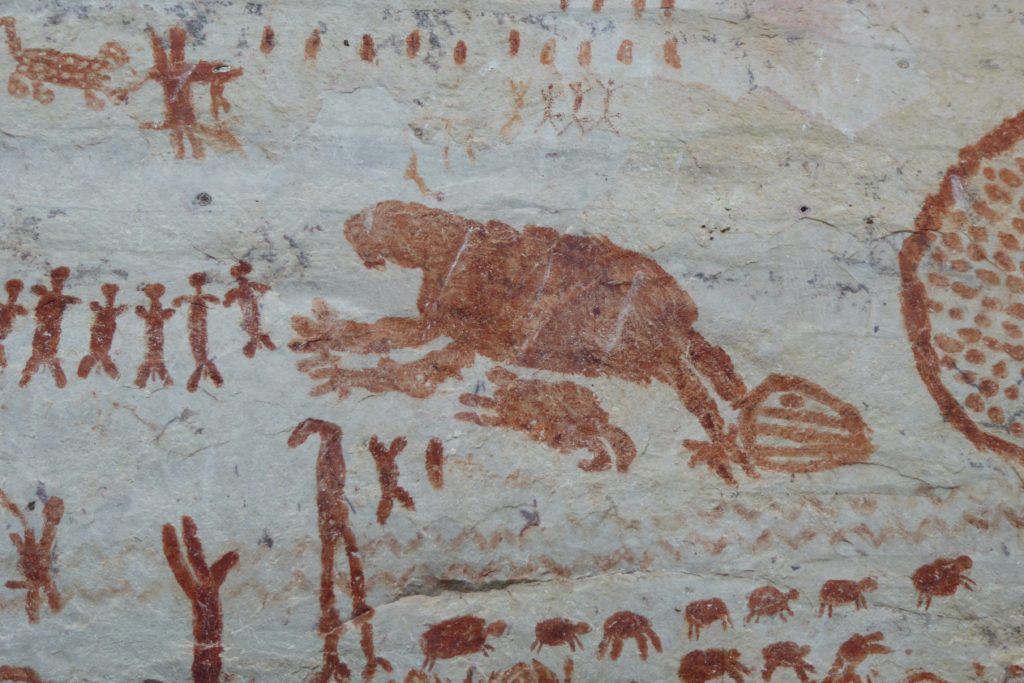

Colombian researchers T. van der Hammen and U.G. Correal dated bones and arrow-head remains from the Magdalena Valley to conclude that humans coexisted with giant sloths and mastodons just 5,000 years ago. They also point to the San Agustin ´Elephant’ statue dating from 3,000 years ago. Were San Agustin people encountering mastodon?

This raises an even more intriguing question: could there still be megafauna still out there living in remote rainforests? This is not as daft as it sounds. Fly in a plane over endless Amazon forests and it becomes almost believable. I mean, there are uncontacted human tribes down there, why not out-of-touch sloths?

The Lost Sloths

Cryptozoologists have been following rumours of giant sloth-like beasts from around South America for decades. People of the remote Brazilian Amazon describe encounters with mapinguari, a 2-metre-high mammal with bad hair, fierce claws, backward-facing feet, a horrible smell and a terrible shrieking cry. Similar beasts crashing around the forests of Bolivia are called jucucus.

For centuries locals in the southern Chile and Argentina have been reporting sloth-like mammals with crazy shrieks and bad body-odour living in remote mountain valleys. These yemisch or lobo-toros (wolf-bulls) drew worldwide interest in 1895 when naturalists found what appeared to be the fresh hide of a mylodon ground sloth in a Patagonian cave, sparking a rush of cryptid hunters and a reporter from London´s Daily Express, one H. H. Prichard. Despite extensive searches, no mylodons or similar were tracked down.

But the Cueva del Milidón (close to Puerto Natalesin Chile, and now a world heritage site) still had some mysteries to impart. In 1899, a deeper excavation by German palaeontologist Rudolph Hauthal turned up a layer of stone tools, sloth bones, hay, charcoal, plant fibres and sloth dung among what appeared to be the ruins of stone corrals. He suggested that ancient humans had used the cave to stock captive ground sloths and maybe even domesticate them, a startling idea that became part of Patagonian lore and the mylodon to be temporarily renamed Grypotherium domesticum, the domestic giant sloth.

Later studies showed the ´stone corrals´ to be natural rock-falls, and the sloth bones dragged to the cave by large predators. Radio-carbon analysis of the slothskin showed it to 10,000-years-old but well preserved by the cold cave air. So it seems unlikely that some proto-gauchos ever had a whacky plan to milk a mylodon.

Anthropologists explain modern tales of mapinguari and yemisch as our ‘folk memories’ of megafauna hunts passed down through generations over thousands of years. That the campfire boasts of our sloth-slaying ancestors still have echoes today is in itself a small wonder. Perhaps this explains our modern-day need to hunt lions with bows, fight bulls, throw darts (which in London pubs are still called ´arrows´) or at least to chase pixelated prey around our smartphone screens.

As for the survival of megafauna in remote places, unfortunately to date no biologist or explorer has been able to find hard evidence of a living specimen. Not that this should stop you looking. But for now, the surest place to spot a ground sloth is in a museum.

PRACTICAL STUFF

In Bogotá there is a complete Eromotherium giant sloth fossil, and other megafauna such as a mastodon, in the Museo Geológico José Royo y Gómez, Servicio Geológico de Colombia, Diag. 53 N0. 34 – 53, Bogotá (close to the Universidad Nacional Transmilenio stop)

The museum is open Monday – Friday 8am-12pm and 1pm to 5pm, and entrance is free.

If you want to see traces of Pliocene megafauna in its natural habitat, travel to the Tatacoa Desert in Huila. Many of the desert campsites have fossils lying around, and there is a small museum with fossils in the small town close to the desert, Villavieja (plus a statue of a megatherium in the town plaza). This town is 1 hour north of Neiva, the departmental town of Huila. I have blogged about the desert here .