Killed in the Darien Gap

- The sad story of Jan Philip Braunisch, a Swedish tourist executed by the FARC in 2013.

- You can find my original story Lost in the Darien Gap on Jan Philip’s disappearance here.

- You can find my post on the safer travel route Colombia to Panama on the Darien Coast here.

- Visit also my post Alto Baudó, Colombia’s Forgotten Corner: another Chocó conflict area.

- For the Chocó’s sunny side, see Spectacular beaches of Nuquí, on the Chocó coast .

In June 2019 I recorded a podcast on on Jan Philip for Semana magazine, with Brendan ‘Wrong Way’ Corrigan

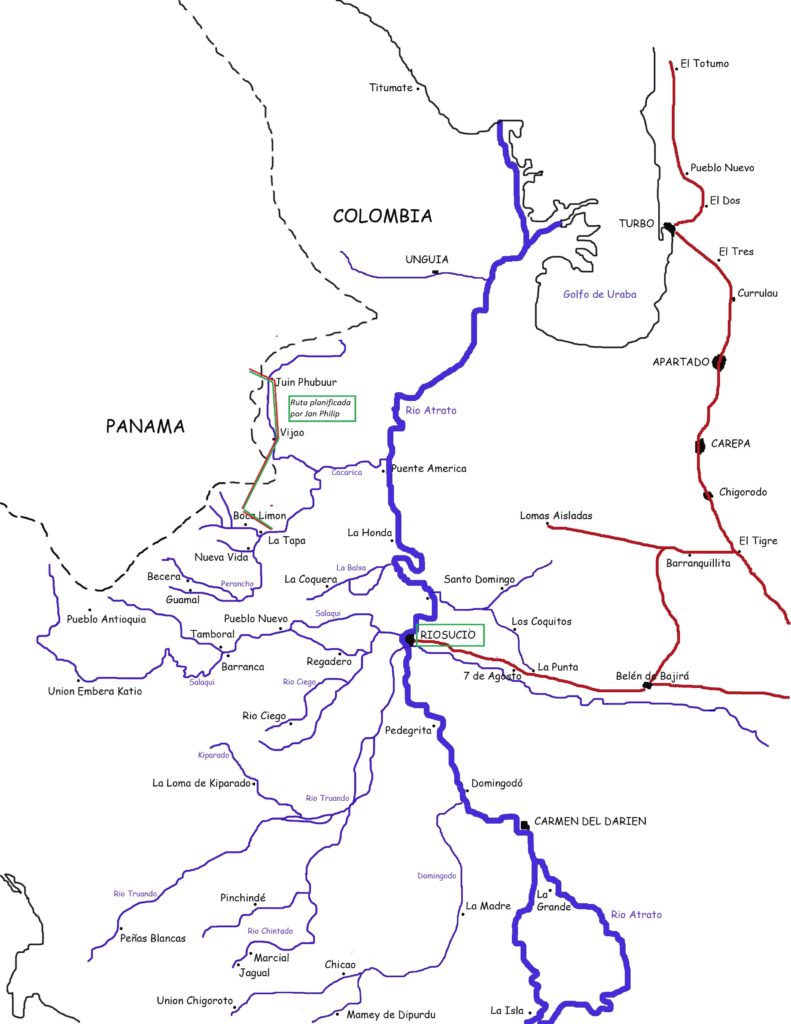

The Darien border between Colombia and Panama, a legendary mountainous isthmus of impenetrable jungle where Jan Philip was captured and killed by the FARC guerrillas in 2013. It’ an old story now, but still relevant as some remote parts of Colombia – including inland routes through the Darien Gap between Colombia and Panama – continue to be insecure.

In 2017 I wrote about the safe route along the coast to Panama, a journey I did with Shiwen, Jan’s widow. It was in part a memorial trip and tinged with sadness. I never knew Jan Philip, but from all accounts he was a kind, caring young man and a brilliant student who had so much ahead. You can also read his blog from 2013, which I have also covered in my Lost in the Darien Gap story.

In those five years I met with dozens of people who had a small piece of the puzzle of how and why Jan Philip died. Most information was given in great confidence. And although we now know what happened to him, there has been no court case, no public results of the official investigation, and no formal follow-up from the authorities. Perhaps this is because murders like that of J-P are common in Colombia, a country still in conflict after 60 years, with tens of thousands of disappeared – and probably killed – citizens. Sadly, he is but one of many victims.

The Retrieval

In May 2015 I got a phone call from the International Committee of the Red Cross ICRC in Bogotá: the remains of Jan Philip were recovered ins a remote part of the Darien Gap and on their way to the authorities in Quibdó, a small city in the Choco state of Colombia. For me it was the end of 12 months of pushing the FARC to release his body, after travelling to the region in 2014 to deliver a letter to their commanders asking them to take pity on the family.

By then everyone knew the FARC had killed him, and why: they mistook him for a spy. But would they confess to his killing? Half way through Colombia’s torturous Peace Process it was unlikely they would want the inconvenient truth to come out: that even after the start of the peace process, FARC fighters had taken an innocent tourist beaten him, pushed him to his knees, and shot him in the head. It was also a secret the government wanted hidden: the state had invested much political capital in the Peace Process and the FARC killing a tourist would not play well in the European halls of power.

Of course, many others were working for the same goal: Swedish diplomats who were in Havana where the peace talks with senior FARC were taking place. They were pushing the FARC leaders hard to solve the problem. In Colombia the Fiscalia (prosecutor’s office) had investigators travelling in the area where Jan Philip disappeared, were working with Army Intelligence to unravel the mystery, and trying to get information from communities. But they faced an almost impossible challenge.

The area where Jan Philip went missing, the Atrato River and Darien Gap, were largely no-go areas for state forces including police and investigators. Years of internal conflict had rendered these zones safe havens for drug gangs and guerrillas who fiercely protected their camps and settlements both in Colombia and Panama. Mixed in with this were civilian peasant communities, humble farmers, and indigenous tribes the Wou’nan and Embera Katio, who also had good reasons to keep the Colombian state at arm’s length.

But even the FARC in Havana were having problems to give orders to their own troops in the Darien. Despite the ‘peace process’, the military campaign against the rebels was full on, FARC units were being to go rogue, and in particularly in the wild and mountainous Darien it was hard to keep in touch with the 5th and 57th fronts that mostly protected the lucrative cocaine and arms smuggling routes into Panama and beyond to Mexico.

The Contact

Eventually the FARC 57 Front based in the Darien Gap realized the game was up. In Quibdo, the capital town of the Choco province where J-P disappeared, a guerrillera delivered us a hand-drawn map showing the location of the body. It was too badly drawn to be of any use but did indicate the guerrillas were wanting to reach out.

All through 2014 I got garbled messages from people I knew in the Darien: the FARC were telling them that ‘killing the Swede was a mistake’ ‘ he couldn’t explain why he was here’. These half-hearted apologies were sent to me by trusted intermediaries, and in return we asked for one thing: send the body home.

Then in April 2015 I got a phone call from someone in the Choco, close to the Darien Gap: the body will be released. I rushed down to the ICRC offices in Bogotá. As the ‘neutral agents’ in the Colombian conflict, the ICRC was tasked to retrieve people and bodies from the war zones. Now they just had to wait for a safe moment to get the body.

When it happened a month later, the handover was done in the muddy Atrato River, close to the town of Riosucio where J-P filed his last blog entry exactly two years before. A canoe with outboard motor approached the ICRC motorboat at a prearranged spot and a box with the skeletal remains of Jan Philip handed over.

The ICRC boat and cargo drove eight hours up the windy Atrato to the small city of Quibdo, the departmental town of the Chocó and the remains handed over to the hospital there. The remains were sent to Bogotá for forensic analysis and DNA confirmation: by the first week of June 2015 we got final confirmation: Jan Philip was dead.

The Denial

This lack of communication with his troops was a major theme of Pastor Alape, a senior former guerrilla commander and FARC leader in the Peace Process, when I had coffee with him in Bogotá in June 2017.

‘We had problems to find out what happened to the Swede because of bad communications,’ he told me. State spies were expert at intercepting cellphones then pinging the locations and calling in airstrikes: he had lost a lot of friends this way. The G’s relied on old HF radio technology that was hard to communicate clearly with. ‘We would go weeks without messages’.

Alape told me J-P was ‘killed in cross-fire between armed groups’, an accident out of their control since the tourist had wandered into a war. True, the Cacarica River where J-P had set out hiking in May 2013 was a ‘hot zone’.

But I had Jan’s autopsy report which showed graphically how he had been killed: with bashed ribs and neck vertebrae and smashed cheek bone from blunt blows (probably a gun stock), then a single pistol shot that blew off the side of his head. This was a beating and an execution. It also chimed with rumours we had heard for several years: the FARC had beaten and killed him. I threw an autopsy picture across the table to the FARC chief. ‘Please explain that.’

The Migrants

Alape looked shocked and ‘promised to look into it’, then quickly left. Did he know the full story or had his own troops lied to him? I knew he was one of the FARC’s toughest negotiators, a hardened fighter who had suffered great personal tragedy in his life with many of his family tortured and killed by right-wing death squads for their political views. Did he care about Jan Philip? I would never find out: he never contacted me again.

In rural Colombia the FARC were sometimes seen as a benign force with the locals for two reasons: many locals were supporters of the FARC, having been abandoned by the state. And the FARC needed the locals to provide shelter, food and intelligence. But the relationship was often a tense one, particularly in the Choco province of Colombia that envelops the Darien Gap, with new ex-paramilitary armed groups vying for space and the more frequent army incursions and bombings.

I was on duty in Bogotá in 2011 when a medical team I was managing was working in Bijao, an Afro-Colombian village in the Cacarica River. FARC entered the village and executed two villagers accusing them of being ‘moscas’, spies for the army. Two years later, when Jan Philip was in the same village, it was a waypoint for undocumented migrants crossing to Panama. Yes, migrants come from Africa and the Middle East via Brazil and Venezuela, trek across Colombia to cross the Darien into Panama, destination USA.

Migrants traversing the Rio Cacarica close to the border with Panama (still from SBS documentary)

The FARC and other armed gangs manage the ‘coyotes’ that guide groups migrants over the jungle trails to Panama. This astounding video from SBS shows the tough reality of where Jan Philip was heading. The migrants pay hundreds of dollars for this rough crossing. Many never make it.

The Unexpected Visitor

Jan Philip loved to walk, and his goal was to hike to Panama. The legendary ‘Darien Gap’ walking trail has been described as the ‘Mount Everest for backpackers’. It was a tough but transitable route in the 1980s and 1990s, but rarely used by foreign tourists since then. But to get to the trail you need to take boats and canoes through the Choco’s tropical wetland swamp and flooded forests.

I know because I travelled the same route as him in 2011, as part of work I was doing in Juin Phubuir, a Wou’nan Indian village that lies on the migrant route close to the border on the upper reaches of the Cacarica River. I went there as a guest of the community under the umbrella of an international health organization. Even then we were wary: armed groups were everywhere and not friendly.

This zone is the spearhead of their dirtiest work: arms and drugs smuggling. Not the kind of work that the feelgood’ guerrilla group like the FARC wants people to know about. When Jan Philip went there he took the FARC by surprise; he wasn’t a migrant, and he had a camera, a compass and a Kindle (which they mistook for a tablet). He was unexpected and unwelcome.

The Boat Trip

To get to the border, on May 15, Jan Philip set off early in the morning from the small port town of Riosucio on a public motor boat, Mi Hermano y Yo. He was travelling with locals down the Atrato River, then turning upstream into the Cacarica river system at a small floating riverside gas station called Puente America. From here in is a no-go zone for Colombian state forces.

The Marines control the main river with their Piraña Gunboats but rarely enter the smaller streams where they can easily be ambushed by guerrillas. Local farmers and settlers, on the other hand, can enter these zones if they are ‘known’ and trusted by the FARC.

The small boat would have pushed through the swampy cienagas inside the river entrance and made landfall at a village inside the river system, maybe La Tapa. Here started the higher, drier ground with walking trails that campesinos used to connect the inland communities with riverine villages.

When and where did Jan Philip meet the FARC?. We know now he was killed deeper into the Darien Gap. But it would have been unlikely – almost impossible – for him to have journeyed on foot or by boat into the Cacarica area without the FARC knowing this stranger were there. The FARC have only survived decades of war from a much stronger enemy – the state – by cunning and skill and having spies everywhere. So did the FARC meet and detain J-P in the lower Cacarica area? Possibly.

The Interception

Some witnesses say the FARC took him out of the motorboat Mi Hermano y Yo in La Balsa, on the Rio Atrato and close to the entrance of the Cacarica. Many of the garbled messages I heard were ‘we told him not to come but he would not comply’ (‘no hizo caso´). Did the FARC detain him before entering the Cacarica and warn him to turn back? Did he ignore the warnings? Or maybe not understand them?

The Hermano y Yo continued down the Atrato River to the sea and port of Turbo. Somehow Jan Philip got free of the FARC and entered the Cacarica River – probably in a smaller canoe – and found his way to dry land.

The Trail

Then the tall Swede was seen walking along the trail from Boca Limon to Bijao. This walking route goes through higher ground and passed several communities such as Nueva Esperanza.

In 2013 I had talked to a local from a village along the trail that told me he had seen J-P walking on the trail ‘like a crazy guy’. ‘He was tall, dressed in black, hardly carrying anything and was crazy – he was wearing sandals’, said one. The last detail was telling because J-P only ever wore sandals: on his blog kit list he writes ‘notably absent are real shoes (I think they’re clumsy, heavy, smelly, give you sore feet, etc)’.

In the Chocó jungle everyone wears rubber boots because of the insects, snakes and thorns. So a tall, fair, European with a small rucksack and sandals in the middle of a conflict zone would have been a rare sight. In fact, local told me it was at least a decade since they had seen any tourists in the area.

The two had a conversation, details of which the campesino told me which made it was definitely Jan Philip he had talked to on that muddy trail. It was mid-morning, the sun was hot, and Jan Philip was walking hard to get to Bijao, the next village along. He did not need directions and ‘seemed to know where he was going’, the farmer told me. It would be several hours walking to reach Bijao, and Jan Philip did not stop too long to chat.

The Afro-Colombian Village

Bijao is a poor Afro-Colombian village on the banks of the Cacarica River in the Choco, in the heart of the Darien Gap. This humble riverside settlement is also the focus of one of Colombia’s longest-running cases in front of the Inter-American Courts of Human Rights, dating back to Operation Genesis in the 1990s when Colombian state forces, together with paramilitary forces, displaced and murdered many local people.

It is also the hub of the human trafficking of migrants over the border to Panama and a choke point on the route: to protect the armed groups in the area, all other routes are mined with anti-personal mines and booby traps, the locals told me. It is also close to FARC and ex paramilitary camps. If you want to get to Panama you need to pass through Bijao.

It is also the place on the map which is a blank for information on Jan Philip. Although I tried to talk to community leaders via the Bijao community association, no-one wanted to talk. Other people told me though ‘ask the people in Bijao, they know what happened to the Swede’.

The Wou’nan Village

Two hours by canoe up the Cacarica River (now known as the Caño Cristal) is the village of Juin Phubuir, a Wou’nan indigenous village that sits almost on the border with Panama.

When I visited in 2011, I noticed all the villagers had Panamanian brand drinks and snacks: it was easier and safer for them to get supplied from Panama than from the nearest Colombian town (Riosucio, 8 hours by canoe).

Early on in our search for Jan Philip, villagers had told me that someone fitting his description had stayed in the village in 2013. He was with a ‘group of black people’ (African migrants?) and he was ‘relaxed and happy’. This implied he was not held captive. In this case he was probably with a group of migrants waiting to form a group to be escorted by coyotes over the trails to Panama. So close, but he never reached his goal.

The Journalist

Confirmation that Jan Philip made it all the way to Juin Phubur came in 2017 when I met to a photojournalist who worked in the area and was nearly killed by the same FARC group.

The story he told me was amazing. He had travelled to Bijao on December 2014, a year and a half after J-P disappeared. He was a seasoned war reporter who had spent years covering the Colombian conflict, and well known to all the armed groups, and never felt under threat. But in Bijao things turned very nasty. While in the village, a group of FARC came and took the journalist to kill him: ‘I was never so scared. I had to negotiate for my life’ he told me. FARC normally respected international journalists – it was in their interests to sell themselves – but this group were ‘hard core’, he said.

Very shaken, the journalist left and travelled by canoe to the Wou’nan village at Juin Phubur, the same route taken by Jan Philip 18 months before. In the beautiful village, with traditional thatched tambos, he could relax. But not for long. Soon after his arrival a canoe full of fully-armed FARC guerrillas arrived at the beach in the village. They were looking for the journalist.

When the FARC had gone, the villagers told him the full story: a year before the tall European had come to the village with the plan to walk to Panama. He stayed three days in the community, and was popular, entertaining the kids and having fun. Then the FARC group arrived by canoe looking for the tall Swede: the same group that had come for the journalist, and the same that had stopped him and nearly killed him in Bijao two hours downstream.

‘Hide,’ said the villagers. ‘They have come to kill you’. The journalist initially refused: he was a tough guy used to facing down danger. But the villagers pleaded: ‘Please hide, they will kill you, like they did the foreigner last year’. The journalist hid.

The Taking

The Wou’nan villagers told the journalist that 18 months before the FARC had taken the Swede from the village and killed him. But where exactly? This is where the story gets hazy. Wou’nan villagers had said he was taken by the FARC in Juin Phubuur, taken to the mountain nearby and ‘shot in the head, and buried there’.

Other sources reported that he was taken to a FARC camp ‘two to three hours walk’ from Bijao and killed there. People from Juin Phubur also told me ‘the Bijao people know what happened to him’. It is hard to piece all the different stories together, but we can try.

The Hypothesis

If we assume all the stories above are partly true then we can make the following hypothesis: Jan Philip travelled by public motor boat from Riosucio to La Balsa where he was taken away by eight FARC, as witnessed by other passengers, and interrogated and set free, probably with a warning.

J-P’s minimalist travel kit looked suspicious to the FARC. Was the Swede a spy?

This explains the garbled message I got from the FARC that ‘we warned him, but he ignored us’. He then took a canoe into the Cacarica River as far as Boca del Limon then walked over the trails to Nueva Esperanza and Bijao, stopping to talk to villagers on the way.

In Bijao he joined a group of migrants, some of them African, and travelled by canoe again to the upper Cacarica River to Juin Phubur. There he stayed with the Wou’nan villagers while the migrant group prepared to move on to Panama. The FARC 57 Front, meanwhile, realized that the foreign tourist – not a migrant – had gone upstream and was planning to cross along the smugglers’ trails to Panama. They sent a boat to find him in Juin Phubur and took him back downstream to Bijao. From there he was marched to the FARC camp two hours into the mountains.

The Guerrillas

The FARC who took Jan Philip were from a squadron of only 12 men and women, part of the Front 57 who patrolled the Cacarica River and western Choco. Their job was to protect the lucrative smuggling routes to Panama, and they had presence and camps on both sides of the border. In May 2013 they were under pressure from the army, air force – camps had been bombed – and desertion of their own soldiers.

The Peace Process was underway, but this had paradoxically intensified the conflict as the two sides – the FARC and the State – jockeyed for position at the Havana negotiating table. They also had a tense relationship with the ex-paramilitary drug gangs in the area, the Rastrojos or Urabeños (later called Autodefensa Gaitanistas).The simplistic reading of the Colombian conflict is that left-wing guerrillas and right-wing paramilitaries are lifelong deadly enemies.

The reality is a complex panorama of turf wars, strategic alliances and switching sides. Many paras were former guerrillas and vise versa. In the Choco the various gangs were often united in the serious business of getting cocaine over to Panama, a trade that benefitted every armed group. A priest who worked in the area told me the FARC there were ‘more narcos than guerrillas’.

The Commander

Rodolfo, the commander in charge of the platoon in the Cacarica, was 47 years old when he crossed paths with Jan Philip. The Chocoaño had been in the ranks of the FARC for 22 years and risen to the political directorate of the 57 Front, but was demoted after killing two ‘indigenous’ people ‘without permission’ (were these the same two people executed when the medical team I worked with was in Bijao in 2011? Possibly).

For most of its history the FARC was a hierarchical, disciplined and bureaucratic, but very effective, rebel army whose fighters followed strict rules. That was in part the secret of its success and the fact that in 60 years the Colombian state never beat it.

In some areas of Colombia where the state hardly penetrated – like the lower Atrato River in the Choco – the FARC were often perceived as benign by the locals. In some areas the FARC were the only ‘government’ the people had known, and State troops were seen as hostile.

To maintain this control the FARC had to exercise some form of authority with rules and justice. For a FARC guerrilla to execute civilians without permission was a crime within the organization.

Even by FARC standards, Rodolfo was a maverick: too close to the local paramilitary groups, extorting money from local communities, and sowing terror in communities along the Cacarica. He did this to keep people out of the area and was obsessed by spies and ‘sapos’ (infiltrators). He answered to the 57 Front commander, El Becerro, another seasoned fighter who would have been stationed at one of the front’s main camps further south in the Choco.

The Killing

Rodolfo and his guerrillas marched Jan Philip for two or three hours to their camp deep in the Darien jungle.

The tall Swede was beaten and ordered to turn on his computer – his Kindle tablet – and the FARC saw maps that Jan Philip had downloaded from the university back in the US where he was studying.

Remains of migrants who died on the trail to Panama (from SBS docu)

The maps seemed suspicious to the FARC, though for Jan Philip – who liked to use maps and compass to find his way – they were just simple navigation tools. Rodolfo called J-P a ‘sapo de la DEA’ – informer for the Drug Enforcement Agency’ (the US agency most feared by drug traffickers) and called the Front Commander, El Becerro, by HF radio for instructions. ‘You know what to do,’ came the reply.

Rodolfo called a ‘council of war’ among his platoon and gave the order to kill Jan Philip. Eight hours after he was first detained, at around sunset, Jan Philip was kicked and forced to kneel, then shot in the head with a 9mm pistol from 1.5 metres away. His body was buried in a shallow grave close to the camp.

Timeline 2013

16 May:

Riosucio – La Balsa, 6am to 7.30am on the Atrato River by motorboat, detained by FARC on the riverbank at La Balsa. Boat continues to Turbo. Jan Philip released by FARC with warning (?).

La Balsa – Boca Limon, local canoe? 1 to 2 hours.

Boca Limon – Bijao, walking on track past Nuevo Esperanza (seen around 11am).

17 May?

Bijao – Juin Phubur, local canoe with migrants (?)

17 – 19 May

Juin Phubur, spends three days with community

19 or 20 May (?)

Sometime in the morning taken by FARC by canoe back to Bijao (1-2 hours). Walked for three hours to their camp, interrogated and killed at 6pm.

Aftermath

For Jan Philip’s family and Chinese wife, Shiwen, the two years following his disappearance in May 2013 were a waking nightmare. Strong rumours suggested he was dead, killed by an armed group, but they always clung to the hope he may have now been kidnapped and released. The return of his remains in 2015 brought intense grief but also some closure. These remains were handed over to the Swedish Embassy in July 2015 and placed in the ossuary in the Jardines de Paz, the large cemetery in the north of Bogotá.

Colombian and international media briefly covered the case in June 2015, when the forensic reports leaked to the press, with the conclusion that J-P was murdered and the FARC were responsible.

By 2015 the Colombian State – FARC Peace Process was making slow progress, and a shaky cease-fire in place. The 57 Front was one of the least likely to surrender.

On March the 8th of that year the commander of the 57 Front, Jose David Suarez, alias El Becerro, who by radio had ordered the murder of Jan Philip, was himself killed in a ‘shoot-out’ with the army (other sources suggested he was assassinated).

Meanwhile between 2013 and 2015, another 60 guerrillas from the Front 57 had handed themselves in as part of the ongoing peace process. This youtube video relates some of their displacement to ‘demobilisation camps’ in the eastern Choco close to the town of Belen de Bajira, as part of the Peace Process to return to Colombia society. This video traces the lives of some of the 57.

Some of these demobilized guerrillas were from the platoon that killed Jan Philip. The Platoon commander Rodolfo was not among them.

Another killing

What happened to Rodolfo? The guerrilla who probably pulled the trigger has never been detected in the demobilization process. Perhaps he joined the dissident FARC groups made up of some 2,000 fighters that refused to demobilize and still dominate some remote parts of Colombia. Or maybe he joined the ex-paramilataries or ‘BACRIM’ (banda criminals) such as the feared Urabeños.

Then another theory emerged: recently a missionary priest recounted to me that in 2015 he was working in the Atrato River area when he heard of a FARC guerrilla who was ‘called to a meeting’ by his superiors in the River Salaqui (just south of the Cacarica) and executed. His crimes were for ‘collaborating too closely with paramilitary groups, causing problems with the communities and killing people without authorization’.

Did the FARC kill Rodolfo?

A Cover Up?

Information exists that suggests when Rodolfo killed Jan Philip in 2013 he had permission from his Front Commander, El Becerro. And in the days after the killing, the FARC were openly bragging to communities along the river that they ‘had killed a DEA spy’. But within weeks they realized their terrible mistake and were ordering communities along the river to ‘shut up or suffer the same fate’. But how far up the chain of command did the truth go?

The 57 Front was a part of a larger FARC unit, the Ivan Rios Bloque, managed by two top FARC leaders: Ivan Marquez (Luciano Marín Arango) and Isaías Trujillo (Luis Carlos Úsuga Restrepo). Surely if the Front commander knew, the Ivan Bloque leaders knew too, and Ivan Marquez was a key player in the Havana talks, as was Pastor Alape who I talked to in Bogota in 2017.

It is my belief is that within months of killing Jan Philip on 2013, senior FARC commanders and peace negotiators knew of their mistake. How long could they cover it up? Did they execute Rodolfo as damage control? Could they claim it as a ‘cross-fire accident’ as Pastor Alape told me in 2017?

Senior FARC leaders have a history of blaming their human rights crimes on ‘out of control’ lower ranks. Three US citizens were murdered by the FARC in 1999.

The FARC admitted the killings but pinned the blame on junior ranks but later intelligence intercepts proved that one of the most senior FARC, Mono Jojoy, had authorized the act.

The Truth Tribunal

War crimes in Colombia are covered by the JEP the Jurisdiccion Especial para la Paz, a special tribunal created under the Peace Process with the intention of healing 60 years of conflict. How? By encouraging free testimony, perpetrators of crimes to confess and ask forgiveness, offer reparations, and the victims to be listened to.

The first step was to register Shiwen, Jan Philip’s widow, as a victim of the conflict. This is a right afforded to tens of thousands of Colombians affected by decades of internal strife. But not to foreigners, it seems. Despite various meetings, letters and emails with government officials it seems there was no way to register Shiwen in Colombia: her petition would have to come from China via the foreign office to the Colombian foreign office,we were told,a formidable task complicated by the fact that the primary victim – Jan Philip – was Swedish. not Chinese.

Incredibly, in 2016 the Swedish government had deported Shiwen, a gifted Chinese student fluent in Swedish and legally married to a late Swede, but still living with his family in Sweden. Shiwen had to go back to China to rebuild her life there.

In September 2017, we approached senior staff at the JEP in Bogota to ask we could get his case presented before the court. Surely FARC guerrillas present at his death would be willing to speak out and the case closed? Perhaps it would open the way for some compensation.

According to the JEP lawyers ‘there is no mechanism for individual foreign victims to register with the JEP’. Victims came through organizations or social structures in Colombia. The Chinese wife of a Swedish tourist was so off their radar they did not know where to start. Maybe with the Swedish Embassy? After some meetings and e-mails it was clear the Swedish Embassy was not interested in helping put the case to the JEP either. Then in 2018, I made an official request to the Fiscalia to push the case to the JEP. A lawyer briefly contacted me to ‘consider the request’ then nothing more.

So who did help us? Throughout this story is a hidden cast of characters I have not named, humble people from all walks of life who gave us vital information that I have shared with you above. These are the unsung heroes of Colombia; boatmen, priests, farmers, school teachers who live in conflict areas and risked a lot to get information out and, in some cases, act as intermediaries with the FARC. And also Colombian investigators working locally for the Fiscalia (like the FBI). These tough guys work at the coal-face of the conflict. The ones I met were honest, caring and highly competent, and surprisingly neutral about the conflict having seen the best and worst from both sides.

The Blame

Not much happens in the world without someone being blamed. After his disappearance in 2013 many social commentators said Jan Philip was stupid to go into the Darien Gap, perhaps a logical conclusion. It is also true that Jan Philip was a brilliant but brash young man who was used to taking risks – he had got in trouble before on trips in Asia and West Africa – and had massively underestimated the dangers of the task he had set himself to walk from Colombia to Panama. I also talked to people from Riosucio who had met him there and explicitly warned him ‘don’t go to the Cacarica’. Did he misunderstand them? Or simply ignored the advice?

Either way, the FARC had absolutely no reason to kill him. He was not armed, posed no threat to the FARC troops, was never given a chance to defend or explain himself, and was clearly European and unlikely to be working for US intelligence services.

And even if he was a ‘spy’, there was no need to execute him. The FARC were already in a Peace Process with international support – including the US – and the FARC had everything to gain by releasing him unharmed, or swapping him for a jailed guerrilla (a common practice in the Colombian conflict). This exactly is what happened to Kevin Sutay Scott, another tourist kidnapped by the FARC while trekking in eastern Colombia in June 2013 (and who was a US citizen with a military background). In his case he was released unconditionally four months later.

The killing was the FARC’s mistake, not Jan Philip’s. The guerrilla organization that purports political ideology had acted no better than a backstreet drug gang.

A Conclusion

Jan Philip’s story as presented above has been pieced together from a tangle of information from multiple sources. It can only be finally confirmed by the surviving FARC guerrillas present in May 2013 when they detained the Swedish student. They could give their testimony before the Jurisdiccion Especial para la Paz. But with a backlog of tens of thousands of cases, this could take time. Or maybe never.

The inconvenient truth of Jan Philip’s death is awkward for the FARC who now campaign in Colombia as a political party, and who rely on European goodwill – particularly in Sweden – for their ideological projects.

So maybe what I am writing here is the last word on Jan Philip Braunisch. In which case, I hope I got it right. I will make any changes in the future if new information comes along. So please check for updates.

So can we now cross the Darien Gap?

Since Jan Philip was taken in 2013, the FARC have made peace, but the Darien continues to be a lawless place with smuggling, human trafficking, illegal armed groups and physical hardships. It is still very dangerous.

There are much less risky ways to cross into Panama, by boat along the coast, see the last section of Lost in the Darien Gap post.

Some brave souls have made it across recently, mostly film makers and explorers. Here are some links:

– US veterans on motorbikes crossed from Panama to Colombia via the Cacarica in 2018, as written up in Playboy here.

– a CBSN documentary also walking the gap with migrants

– here you can read journalist Jason Motlagh’s account of making the SBS documentary (see above)

15:36

Terrific story and details. Kudos to a courageous foreigner (?) in Colombia.