On the road in Colombia

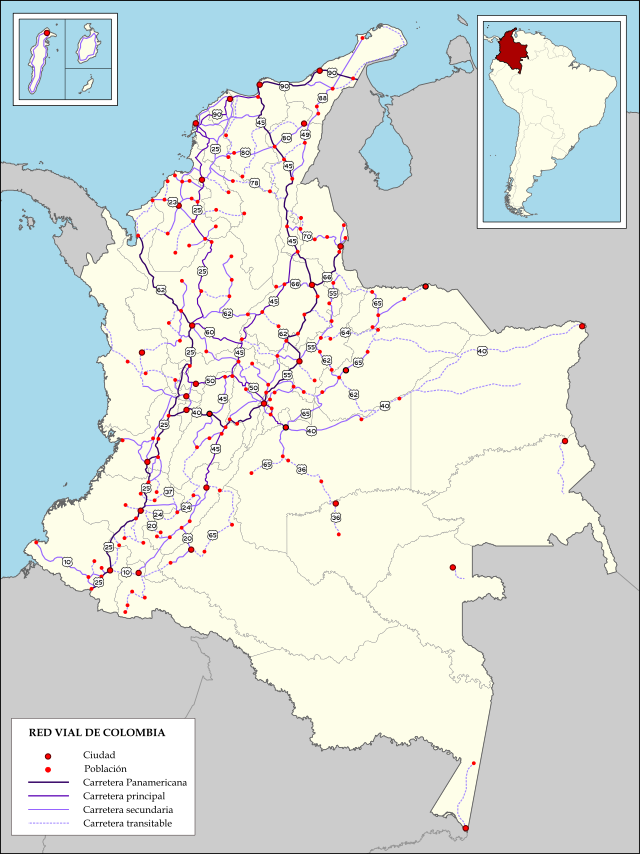

Colombia is a big country where major cities are one to two day’s drive apart, there are three mountain chains and a lot of jungle to deal with, and plenty of other natural (and man-made) obstacles along the way. The country has justification to blame its poor transport development on its unforgiving geography. The severe La Niña floods that ravaged the country in 2011, for example, took out hundreds of bridges and long sections of main roads.

In recent years Colombia has started to catch up with its neighbours with large-scale projects, such tunnelling through mountains and building lofty viaducts to span valleys, proper dual carriageways etc. to create a modern network of highways.

But it all goes painfully slowly and there is a frustrating lack of up-to-date information on routes, and Colombian media are much more focused on the politics of road-building than practical info like where is open.

Road conditions are better in the dry seasons (normally December to May) and most unpredictable in the wet season (June to November) with heaviest rain likely in October.

You can try the INVIAS (road authority) website but lately it does not seem to be updated very often. The police have a Estado de las Vias page on their website which has no maps but a long and detailed listing of closed or restricted roads, mostly planned closures for road-works or unplanned because of landslides (derrumbes).

PLANNING YOUR TRIP.

1. Get a good map. For long trips on main roads the highway guides you buy at petrol stations are good. Some departments also have a tour guide free online try googling the department and ‘guia’. The Boyaca one is here. Towns are listed alphabetically, but there some also have useful Rutas y Circuitos section with maps. If you really want to explore then buy a large-scale maps of the department from the IGAC (Instituto Goegrafico Agustin Codazzi) close to the National University on the NQS Highway in Bogota, which has a shop, museum and fascinating displays on maps in Colombia. Google or Bing maps are help, but often lack place names (or put them in the wrong place for small villages). I have put some route notes and maps in some of my block pages, such as the route from Cali toTierradentro, or the back-road to the Tatacoa desert.

2. Try not to drive at night. Colombian roads are crazy enough without doing it in the dark, so I always find a roadside hotel at dusk. To compensate I set off at first light (5am) and put a hundred kms behind on mostly empty roads before stopping for breakfast.

3. Add 50% to any ETA: people will tell you that Anapoima is ‘one hour from Bogota’ but after one hour you will still be in Bogota traffic (even during ‘off-peak’ hours) and with luck you might make Anapoima in two hours, but probably three hours. Plan accordingly.

4. Plan to pass through the major cities at lunchtime. Some cities gridlock at peak hours so the last thing you want after a long day’s drive is to be stuck in a traffic jam (plus wondering if you have ‘pico y placa’.) It is much easier to transit cities at lunchtime, when everyone is sitting down to lunch and the roads a bit easier. For example if I am driving from Bogota to Cali (500kms and 11 hour drive) I follow this pattern:

Day one, 1pm leave Bogota, cross the Magdalena River find small hotel in Cajamarca at 6pm.

Day two, 6am leave Cajamarca, arrive Cali 11am

5. Overnighting

Every small town has a several cheap clean family hotels, car parks and somewhere to get chicken and chips. No need to book ahead, even on bank holidays there will be space, so just rock up and chose the place that looks cleanest and a secure courtyard for the car. If you are a family, there are always family rooms with two double beds. I always bring a can of fly spray (to knock out the mosquitos under the bed), bottled water to drink. This is one way to get to know towns that tourists never normally see, such as Guadas (a colonial gem of a town most people just drive past) and La Dorada, a bustling market town on the Magdalena River with a beautiful plaza and great ice cream parlours. Prices can be as low as US$15 a night for a family room.

6. Meals for wheels Colombia’s expanding road network dotted with an increasing array of local-style roadhouses many of which feature large thatched roofs (techo de palma) where you can stuff yourself with bandeja paisa and other heart-attack fodder that will leave you so full you will want to sleep it off for a few hours. The sancocho (soupy stew) is a bit easier on the digestion. Prices can get quite high (US$10 a plate in the posher places) but you can find the same food cheaper if you stop where the truck drivers eat, usually around US$3. There is also a lot of local produce to buy by the roadside, whatever local fruits and veg are grown locally, and I often load up the car with 20kgs sacks of produce if heading for home.

ROAD TOLLS

Privatized road ‘concessions’ squeeze you for as much cash as they can. I just paid US$16 in tolls to drive 200 kms from Armenia to Cali spread over a frustrating 5 toll booths, ranting like Victor Meldrew with each appearance of the dreaded ‘Peaje, 1km’ sign. In some areas you can reduce costs by taking more minor roads, i.e. in the Cauca Valley there is the beautiful Panorama road (Route 23) that runs on the west side of the valley, and has less tolls than the main Panamericana (Route 25). But not many areas of Colombia have these alternatives. I factored a yearly estimate for road tolls in my page on Getting a Car. Note: motorbikes are free, so if you are happy on two wheels then this is a lot cheaper.

DRIVING HAZARDS

In 1995 there were 7,900 traffic deaths in Colombia and you were 18 times more likely to die on the road than the USA. Thing have improved slightly since, in 2012 there were only 5,600 dead in crashes. Some toll booths cheekily sell you a quickie US$1 life insurance plan for the next 50kms. Statistics also show a much higher death rate at night, with a third of all deaths related to speeding and drunk driving. Good reasons to practice defensive driving and to park up after dark.

Nearly all roads in Colombia are dangerous in one way or other. Remote mountain roads have less traffic but also lack crash barriers, retaining walls, proper signals or any other basic safety features. This makes driving more fun for you, but more nerve-wracking for you passengers. Go slow is the best advice.

The main highways will built to a much higher standard and look safer, but then you have to deal with other road users, some of which can be classified as follows:

1. Impatient Prado. Mysterious tinted-windowed Toyota that flashes by so fast you can’t see anyone inside (and probably don’t want to). Best to pull over slightly to allow to pass, don’t wave.

2. Motorbike and mattress. People carry strange things on motorbikes, such as a mattress which the pillion passenger wrestles to keep under control while the driver tries to steer a straight course through the cross-wind. Keep well clear while overtaking.

3. Spam in a can. Small, new, overloaded family car (Chevrolet Spark) revved to take-off speed on a hill descent that flies over all four lanes of the dual carriageway then lands roof-down in the ditch. So make sure you watch both lanes of traffic for incoming projectiles.

4. Oversize trucks. A truck that doesn’t fit on the road and is so heavy it can’t actually stop going up or down the mountain passes, but does have a powerful horn. Take whatever evasive action necessary to get out of its way. Retrospective arguing as to who had right of way is irrelevant and probably only possible via a spirit medium.

5. Bloody Buses. Whereas trucks are benign behemoths just plying their route, the long-distance buses are a malevolent force that will actively try and force you off the road, raise your blood pressure to boiling point, and incite some interesting new English vocab for the kids in the back seat. I have learned to enter a Zen-like trance when seeing a large bus in my rear-view mirror and pull over to let it pass.

OK, so you get the idea. Take your time, stay cool, have a good sound system in the car and play some relaxing music.

THE BACK OF BEYOND

Whereas in most countries are really empty road is a good thing, in Colombia you just wonder: ‘why is no-one else using the road?’ the probable answer being there are guerrillas or other armed groups lurking in the bushes. After 60 years of civil conflict, generations of Colombians have grown up with the ingrained sense not to wander anywhere off the beaten track. Sure, the country is opening up and a lot more accessible than even 5 years ago. But there are still risks. I have tried to expand on these themes in my blog Is Colombia Safe? and Journeyto the Heartland.

Some advice to avoid or deal with unexpected encounters:

1. Many routes are now safer than before, but this is based on political processes (ie the FARC peace process). If these processes fail then the danger can suddenly increase. So watch the news from time to time and keep informed.

2. Do check for other road users, i.e. local buses and cars coming from the other direction. Don’t be shy to ask for updates. Beware of euphemisms to armed groups since most people won’t say it out loud i.e. you will hear ‘inconvientes en la carreterra ’ which could be a large puddle, or a guerrilla road block.

3. Don’t look for trouble and or think it is kind of some kind of adventure to meet the guerrillas. It’s not (read Ingrid Betancourt’s book Even Silence HasAn End if you need reminding ).

4. But don’t assume that armed groups will automatically do you harm. Many will just ask what you are doing and send you on your way (or turn you back).

5. If you encounter people with guns ordering you to stop (in or out of uniform) then always STOP. They will shoot you if you don’t. (Sounds obvious but some people keep driving).

6. Don’t expect the group to explain who they are, and don’t ask (one feature of the Colombian conflict is different groups, and even the army, pretending to be one another).

7. Never leave the car unless expressly ordered to do so, if you do have to get out then stay as a group and resist (firmly but politely) to be split up.

8. If questioned, be honest and simple. Avoid politics or opinion. Don’t offer unnecessary data, like your dad is the CEO of an investment bank. Now is the moment to be grateful your mum’s a teacher.

9. If requested to leave the car (ie to walk into the bush) negotiate to take some basic stuff with you (as much as you can stuff in a bag). The armed groups don’t usually kidnap people these days, but they might ‘detain’ you if it is some advantage to them or they are suspicious of your motives. Mostly they are paranoid about people spying on them, so the trick is to ensure they quickly realise you are a genuine tourist (show them the happy snaps on your camera).