‘It’s the (narco) economy stupid’

A version of this story first appeared in the

Going Local column of The Bogotá Post, in 2017

For related posts see ZeroZeroZero: cocaine rules

The FARC are at peace, but many rural communities remain plagued by violence, revealing the Colombian conflict as an endless tussle over cocaine, its production and distribution. Yes folks, the Marxist guerrillas were just a side-show: the large powdery-white elephant in the room is the US$300 billion-per-year global illicit drug business anchored in Colombia. As Bill Clinton might say, ‘it’s the narco-economy, stupid’.

Of course, the former guerrillas were also up to their armpits in drugs and many predicted that once the FARC resigned its role as overseer-in-chief of large swathes of cocaine-producing zones of Colombia that some other gunslingers would step in to fill the gap. And there would be blood.

With reason, then, some Colombians doubted the peace process. ‘Más vale malo conocido…’, better the devil you know, as one colleague put it to me. On their home ground the FARC had some ideology and restraint. The bunch filling their shoes could be a lot worse.

These new gangs are now called ‘GAOs’, Grupos Armados Organisados, formerly known as BACRIM (bandas criminales), armed groups with leadership and hierarchy who launch attacks on state armed forces and civil society (and frequently each other). According to the government they ‘lack any type of ideology’ and have purely criminal ends.

But just as the ideological FARC drifted into drugs, large drug gangs have drifted into de facto governance of the areas they control. Groups like the Gaitanistas (AGC), La Gente del Orden, Los Pelusos and Los Puntilleros all claim some higher social goal that goes beyond filling the world’s seeming insatiable desire for cocaine.

This stems from their distant ideological roots, either in right-wing paramilitarism or dissident guerrilla groups, but also in how cocaine is made; it uses coca leaves cultivated by campesino communities in small plots over a large rural area, and this zone demands a tight control by the drug gangs through the time-honoured fashion of plomo o plata. Cooperate and get paid, or resist and be killed.

State control was too little too late

In their belligerent phase, the FARC did the drug trade a favour by sealing off large areas of Colombia where coca production could go on unhindered. One key part of the peace process was for the state to reoccupy these areas and assist farmers to replace the coca with legal and marketable crops.

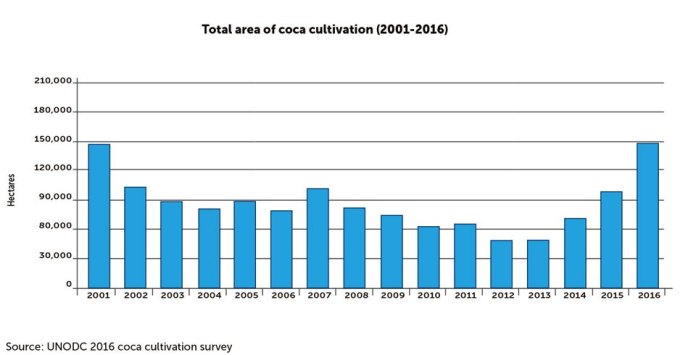

‘They missed the ball on that one, state control was too little too late and new armed groups took over, or the old fighters just changed uniforms’ says a friend who works in rural areas, an opinion echoed by many observers. Meanwhile coca cropping has soared in the last two years leaving President Santos in the uncomfortable position of signing in a peace treaty while illegal drug production – the main driver of conflict in Colombia – reaches a new high.

No wonder most of the murders of social leaders in the last two years – more than 150 at the last count – have taken place in former FARC zones and coca-growing areas, says a recent report by Colombian rights groups. It also points out problems with the Peace Accord plan to engage communities in promoting coca crop substitution. In practice this puts local leaders in the cross-hairs of drug gangs who want more, not less, of cocaine’s raw materials.

In many drug gangs won’t allow farmers to stop growing coca, and there are many stories from rural communities coming under attack for trying to switch to coffee or cacao. And corruption in state forces means some troops in some places secretly plot with the drug gangs. Who can the peasants trust?

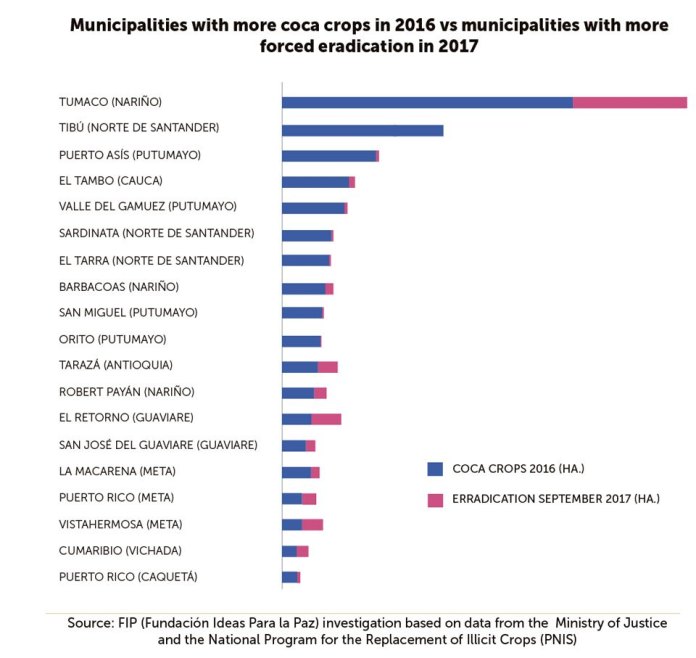

To add fuel to the state has ramped up forced eradication of crops using armed anti-drug police backed by the feared ESMAD anti-riot units, often in the same areas where substitution was supposed to start. This went badly wrong in October in the rural area of Tumaco when police shot dead seven protesting farmers.

Many see this massacre as the predictable outcome of US pressure on Colombia to forcibly eradicate. The US is opposing the substitution plan, having declared it null and void because it was part of a peace deal with the FARC, which in their minds is still a narco-terrorist organisation (despite the fact it has demobilized).

Behind this posturing, the US suspects that the softly-softly approach of crop substitution will be ineffective, like a slow-motion game of whack-a-mole as coca springs up in new areas even while old plantations are slowly replaced with papayas. They also worry that some crafty campesinos will grow coca just to get the substitution benefits.

Some see it as pay-back for the Colombian government’s decision in 2015 to suspend aerial spraying of glyphosate herbicide (a lucrative business for US defence contractors). True, spraying from planes did reduce coca crops but it also wreaked havoc on legitimate crops, neutralising benefits of crop substitution, and since glyphosate is a suspected carcinogen, it is unlikely to come back.

This leaves the only quick-fix option of sending heavily-armed eradication teams to manually uproot coca plants. This is a gruelling task in hostile territory where troops risk landmines and surprise attacks as they labour under a hot sun, exactly the scenario that can lead to on-edge combatants opening fire if they feel under threat.

Legally, state forces can use lethal force against suspected GAO fighters and effectively engage them in combat, or even use snipers to shoot them dead. But the gangs will fight back and, like their guerrilla and paramilitary predecessors, camouflage themselves in the civil community. The outcome is a nightmare for campesinos caught between gangsforcing them to grow coca (and protest its eradication) and trigger-happy state forces sent to eradicate.

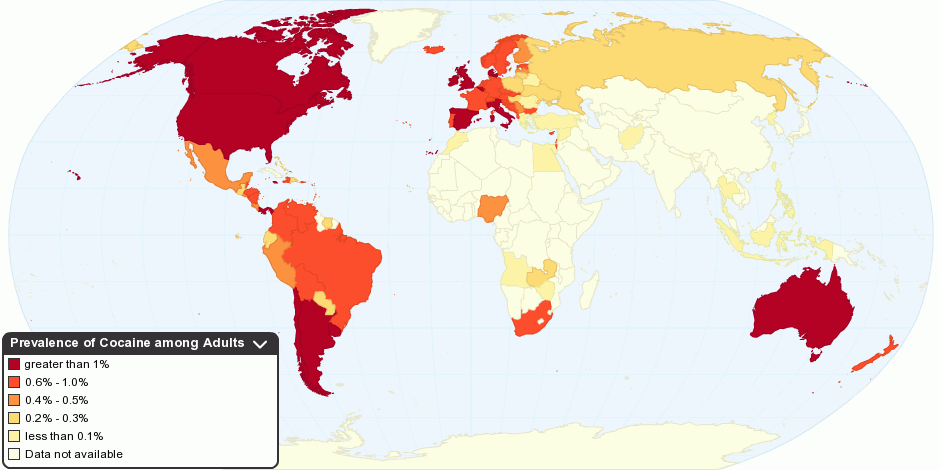

And while it may seem logical to stop cocaine by (literally) cutting it off at the roots, some economists argue controlling coca is a waste of time. This is because US$650 of locally-grown leaves can be converted into 1 kilo of cocaine worth US$7,000 in Colombia, but US$150,000 in New York. With such a huge profit made overseas there will always be excess cash to create relatively cheap coca plantations, no matter what the human or environmental cost.

How much is the overall cocaine trade worth? No-one can say for sure in a business that is necessarily clandestine and constantly evolving, such as increases in cocaine yield per coca hectare. One estimate states that 97% of Colombian cocaine profit stays overseas, mostly in consumer countries, to be laundered through crooked business and banking systems. Only 3% makes it back to Colombia.

Still, this small percentage adds up to more than US$10 billion flowing back to Colombia’s criminal enterprises – more cocaine, illegal mining etc – and more conflict. A large chunk also washes into mainstream businesses, often in the hands of the country’s elite.

These figures also reveal a basic unfairness that Colombian peasants face bullets and endless cycles of violence while overseas the directors of money-laundering banks get a suspended sentence and a fine. Even large players like the Bank of New York and Bank of America have been caught washing cocaine cash over the years.

War on drugs ‘more harmful than all the other wars being fought worldwide’.

Perhaps with reason President Santos declares the war on drugs ‘more harmful than all the other wars being fought worldwide’. Global leaders ‘need to rethink’ the strategy he says, the sub-text being ‘stop picking on Colombia’. His government taking steps to decriminalize small-scale coca leaf production, which also avoids the thorny issue of having to lock up 100,000 peasants. Colombian jails are already full.

But can he get crop substitution back on track? It seems to be a mammoth task, because it is not just about switching crops, but also creating a whole infrastructure of governance and security in the campo, somethingColombia has been historically very bad at.

For a start it needs a paradigm shift in military thinking. After years of being ambushed by guerrillas, state troops understandably see many rural areas as hostile, and are more used to fast-in fast-out counter-attacks than a protective role with permanent presence.

It also will need a lot of resources and right now the cupboard is bare. This has prompted the call last month by the International Crisis Group (see the side story in the ICG report) for the international community to step in and fund crop substitution, either directly or by complementary projects which give the state a benign presence in former FARC areas.

But even with funds can long-term substitution survive the rough and tumble of the coming elections? Already the signs are that tub-thumping politicos will roll back the peace agreements and preach a Rambo response to coca control.

‘So, to get themselves elected they’ll condemn another generation to war while their own kids live in Miami,’ mutters my friend who works in the campo. In his mind urban elite pushing hardest for a ‘war on drugs’ stand to gain most from the ensuing violence. ‘The shit flows down while the money floats up,’ he declares. Meanwhile the equation holds true that coca needs conflict, and conflict needs cocaine. Breaking that will be mighty hard.