Colombia’s fantastical fossils – and where to find them

Colombia had some freaky fauna in its pre-history, from giant sloths, weird mammals, biggest-ever snakes and crocodiles to ferocious marine reptiles. Here’s a guide to getting on the fossil trail and exploring the lives of these ancient beast, many of which were unique to South America. Don’t expect Smithsonion-style mega-museums: palaeontology is not well funded in this part of the world. But fossil sites like Villa de Leyva and The Tatacoa Desert unique finds, and local palaeontologists and keen amateur fossil-hunters are joining forces with researchers from around the world to bring amazing new discoveries every year.

Posted in July, 2023.

See related posts: The Giant Sloth Slaughter, On the Dinosaur Trail in Villa de Leyva, and Adventures in Gorgeous Guaviare. See the end of this post for useful external links.

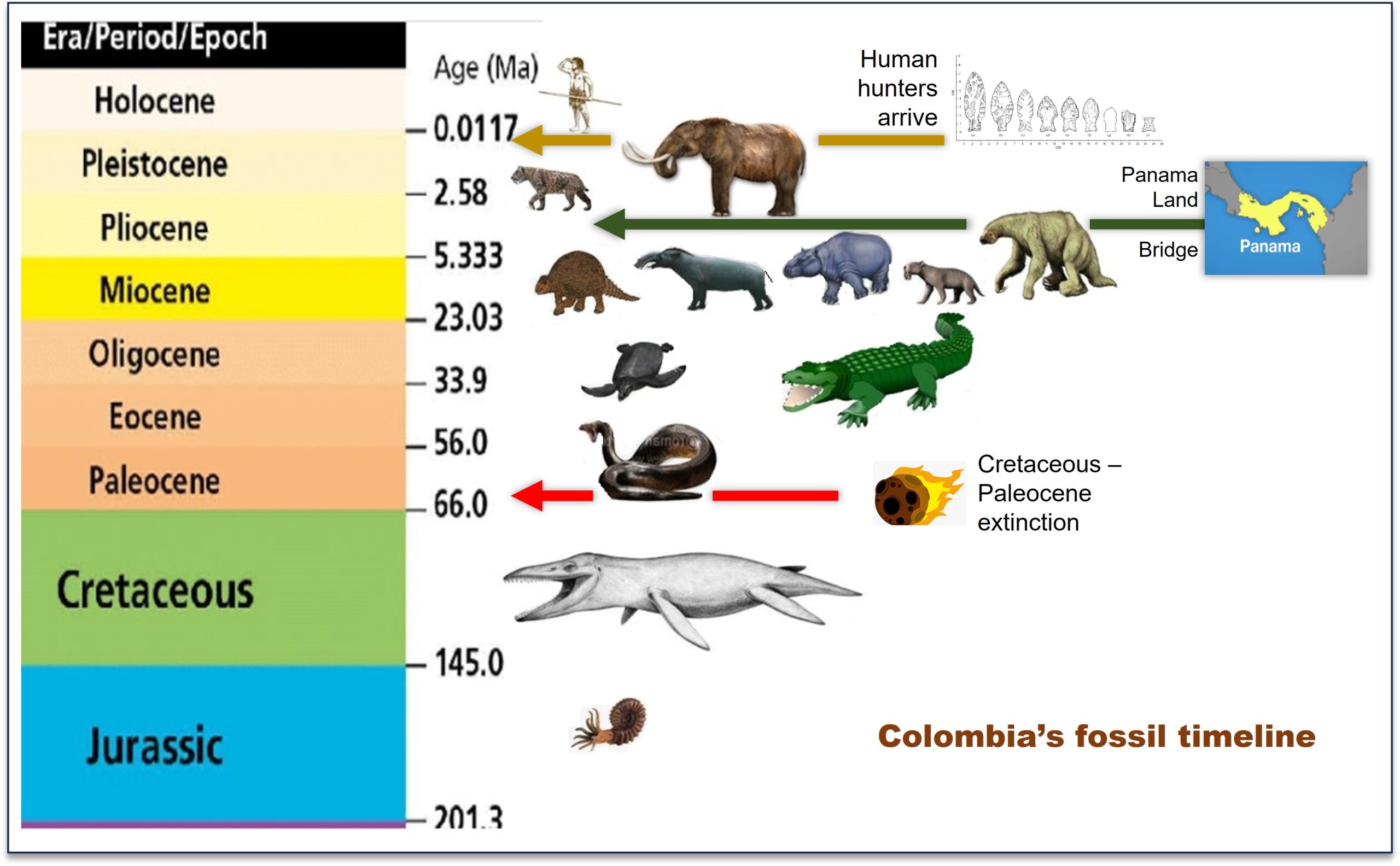

Colombia is recognizeds for fossils from four different scenarios:

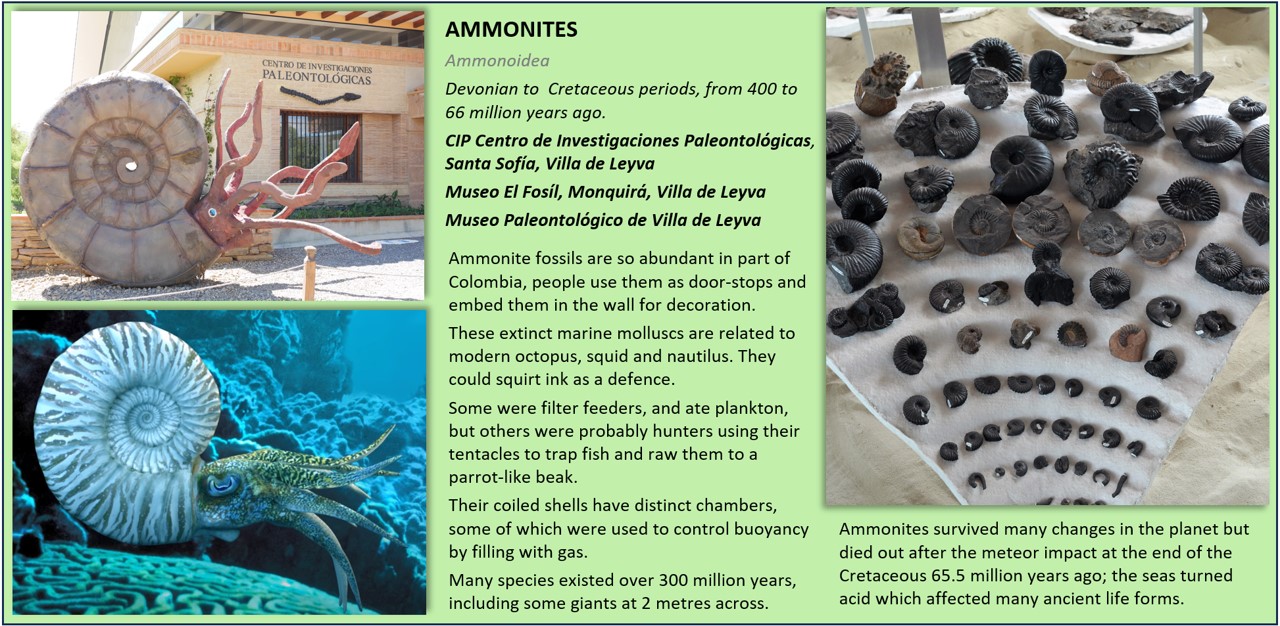

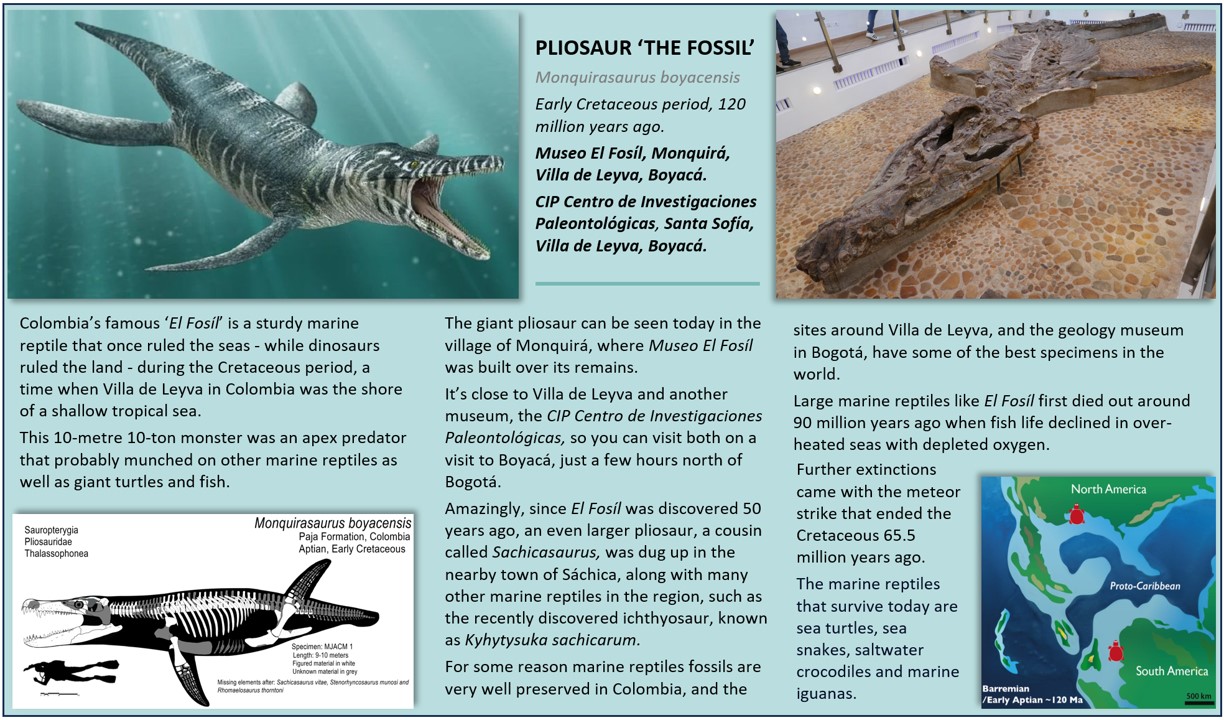

- Massive marine reptiles in excellent state of fossilisation found around Villa de Leyva in Boyacá. These date from before 66 million years ago in the Jurrasic and Cretaceous periods, when central Colombia bordered a tropical sea.

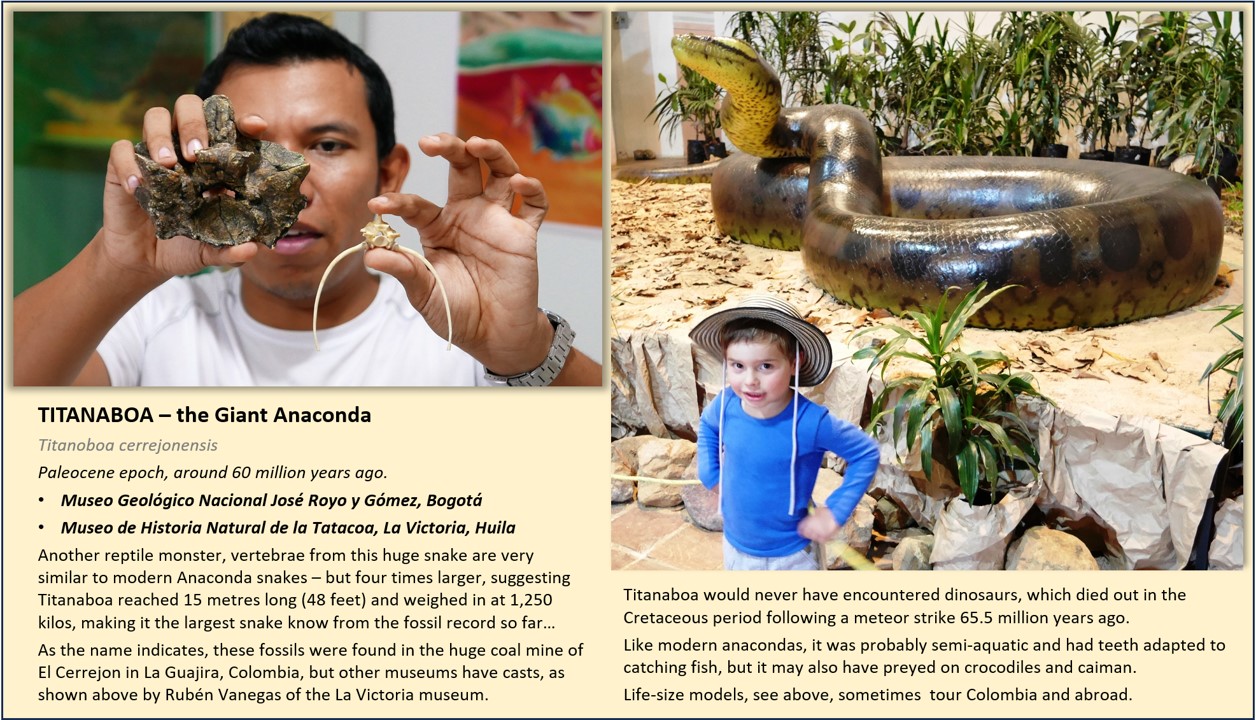

- A truly monster snake – longer than a bus – from the Paleocene epoch, 60 million years ago, found in carbon deposits in La Guajira and from a time when the north of Colombia was dense tropical forests.

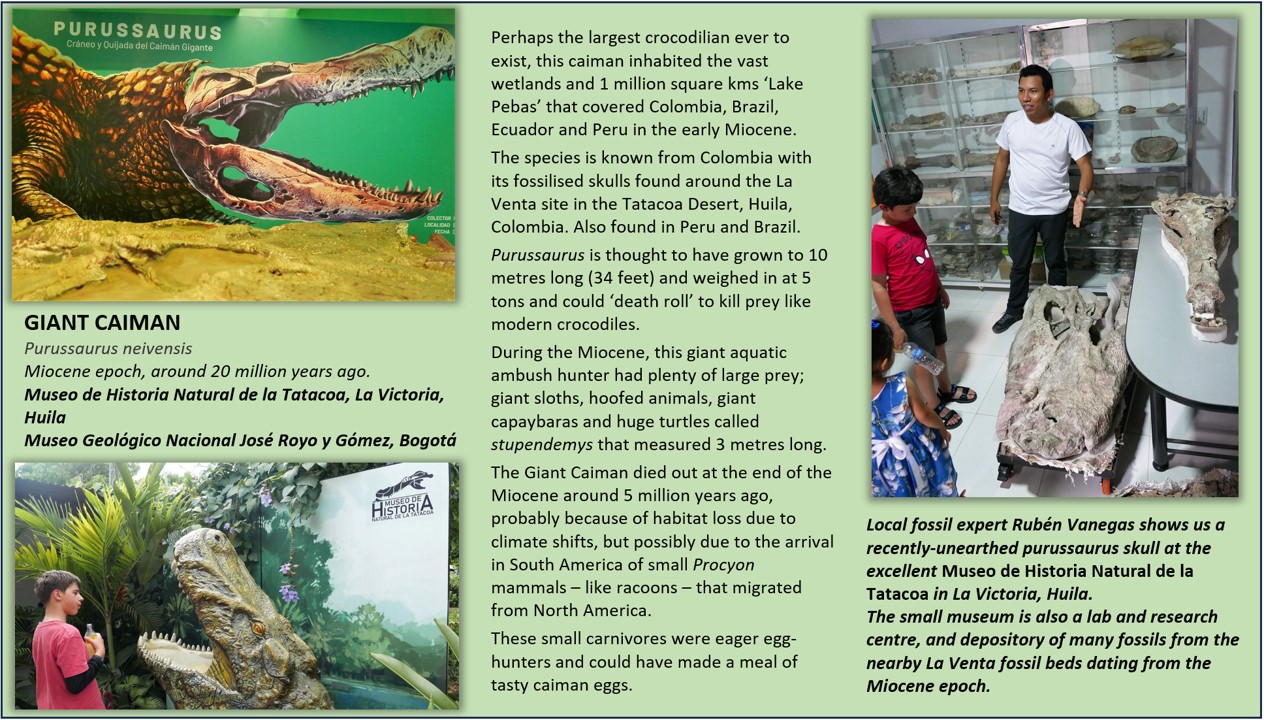

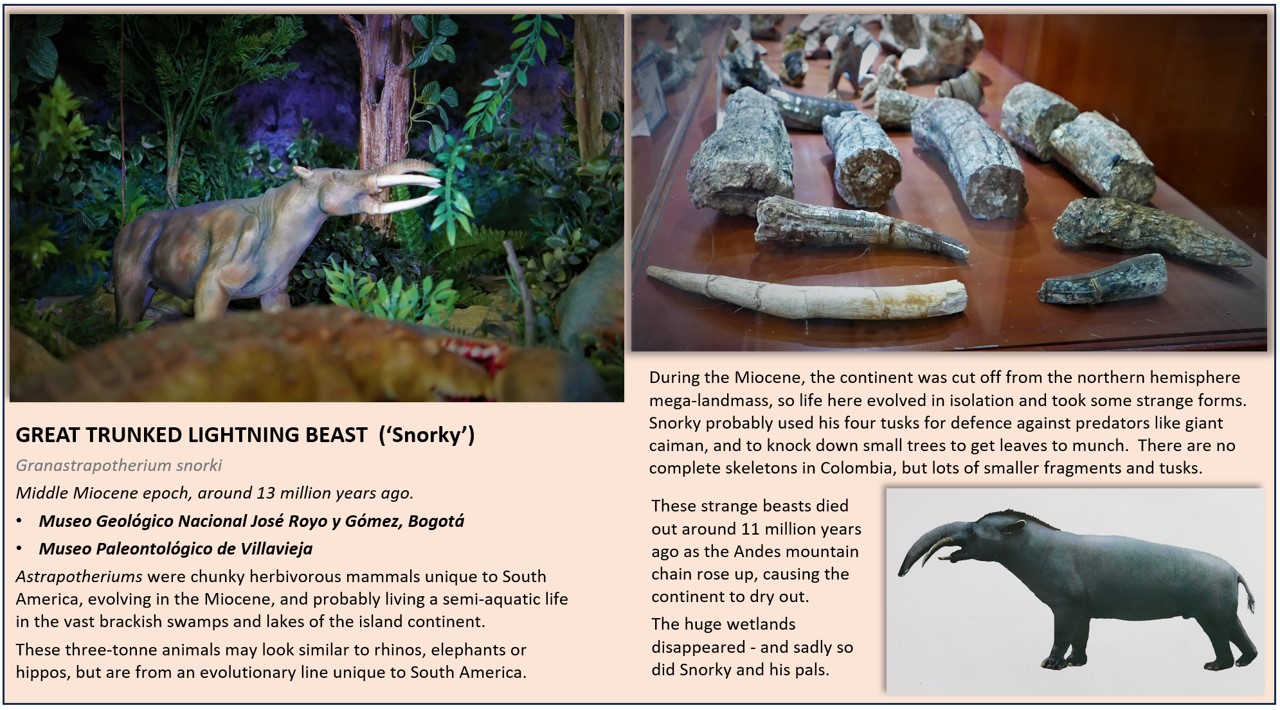

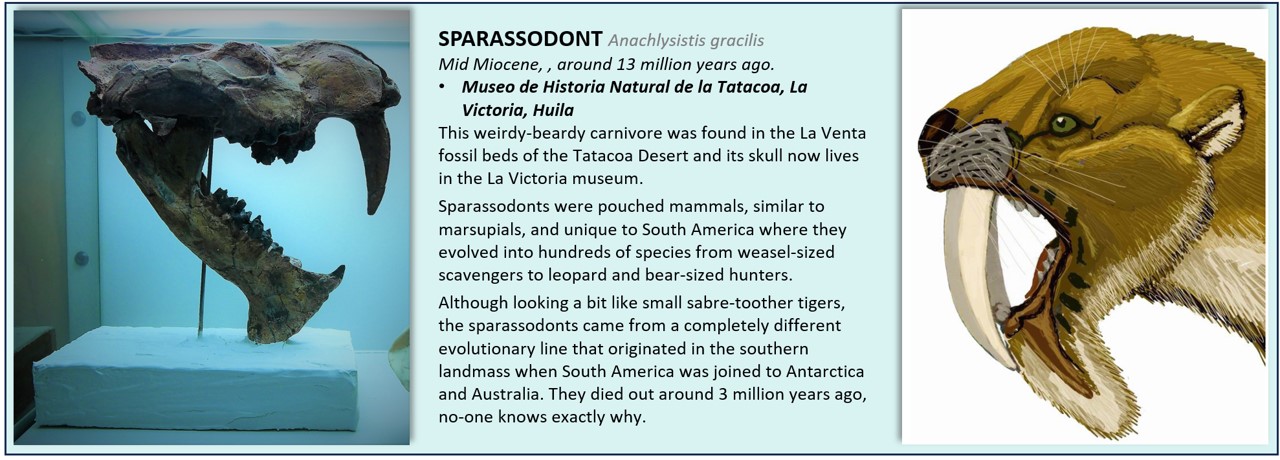

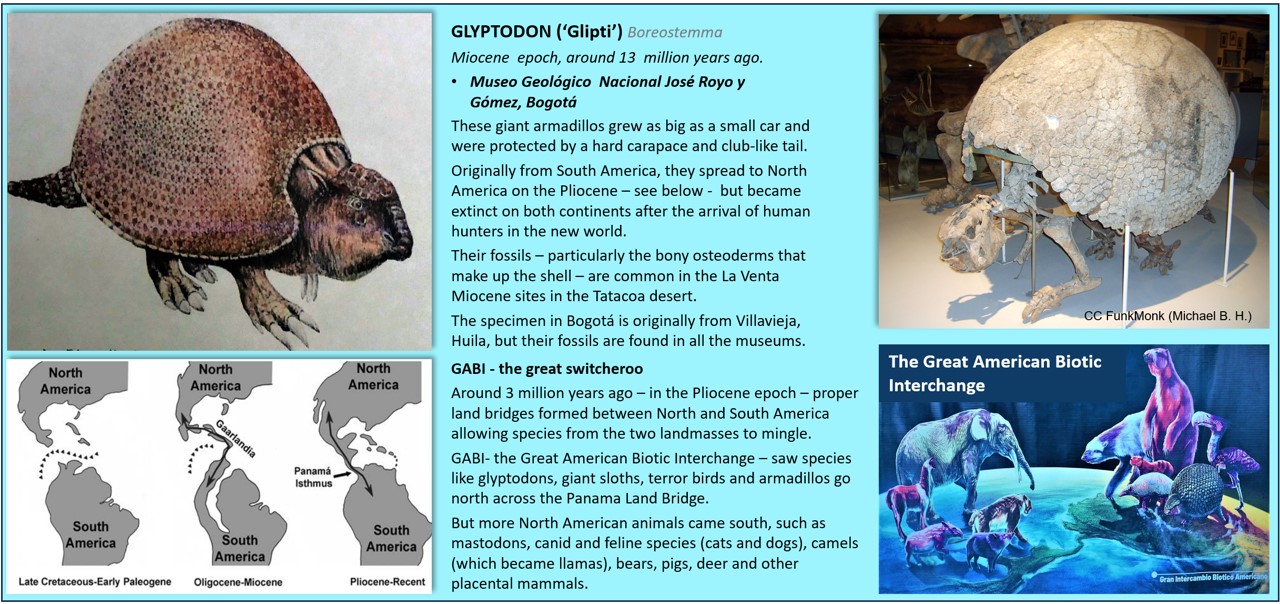

- Middle Miocene animals found in the rich La Venta fossil beds in the Tatacoa Desert, Huila, a few hours south of Bogotá. These beasts date from a time when South America was an island continent and evolved in isolation in weird and wonderful ways, including amazing mammals and giant reptiles.

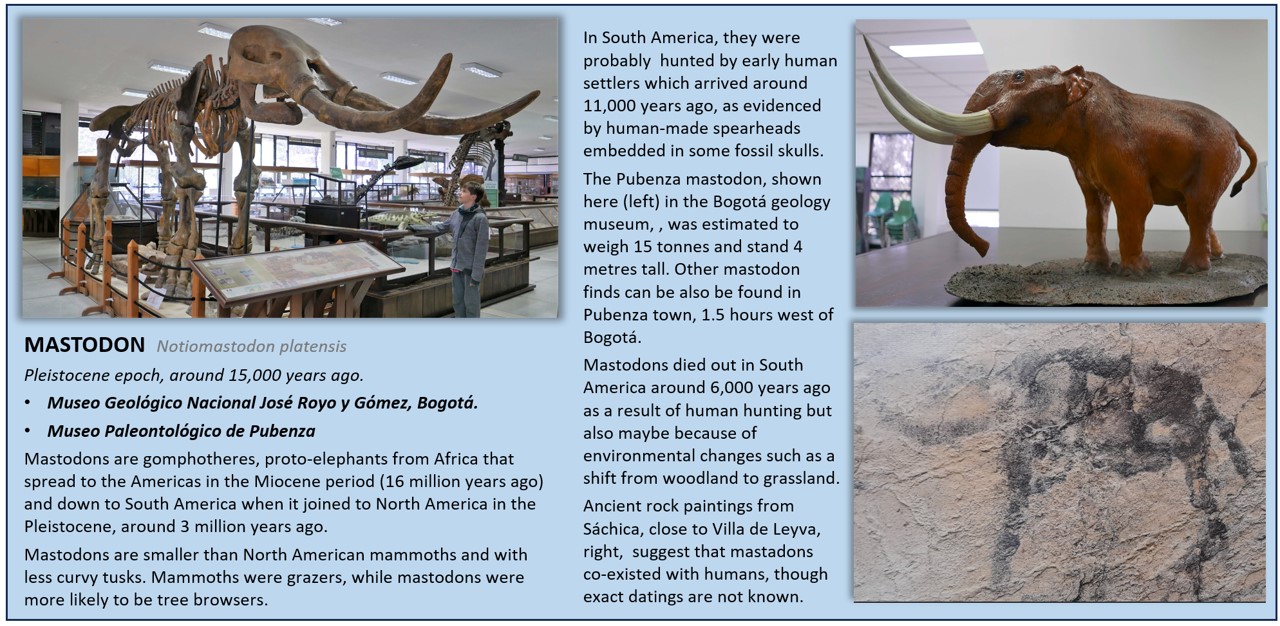

- An invasion of North American Pleistocene animals that migrated to South America, crossing through Colombia, after a land bridge connected the southern and nothern land mass for the first time in many millions of years. Of course a few South American animals also migrated north, but not so many. These fossils have been in many places.

Eventually, of course, around first humans also moved south to populate all of the southern continent. The date is contested; most paleoarcheologists say 15,000 years ago, but growing evidence suggests it was much earlier and maybe even 27,000 years ago. Here’s a picture showing how our fantastical fossils animals fit on the palaeontoligical timeline.

Where are all the dinosaurs?

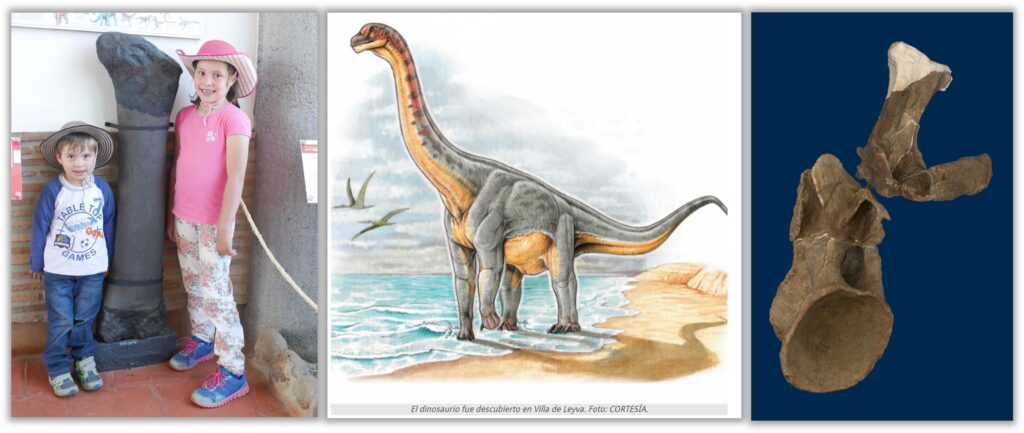

So far, officially, only two dinosaurs have been found in Colombia. Of course, the large marine reptiles that inhabited the Jurassic seas were contemporaneous with the large land dinosaurs, and Colombia has plenty of these fossils. But dinosaurs are by definition land animals with upright legs, which differentiates them from lizards and reptiles.

So what are those two Colombian dinosaurs?

- 18-metre 10-ton sauropod Padillasaurus leivaensis was found near Villa de Leyva and dates from the Cretaceous period.

- In 2021 another large sauropod, but much older – 175 million yeara from the Jurassic – was found in the Serrania La Perijá, previously a conflict zone in the north-east of Colombia. Perijasaurus lapaz refers to ‘La Paz’, the peace process that allowed palaeontologists to study the area it was found.

Both species have been identified from very limited fossil finds, a leg bone and a vertebrae. Get digging to find more!

Ancient seas of the Cretaceous

A very large snake found in a coal mine

More super-sized reptiles

Fantastical fossils from the Middle Miocene

Northern migrants from the Great American Biotic Interchange

The end of an era – another extinction event

What happened to South America’s Miocene mammals?

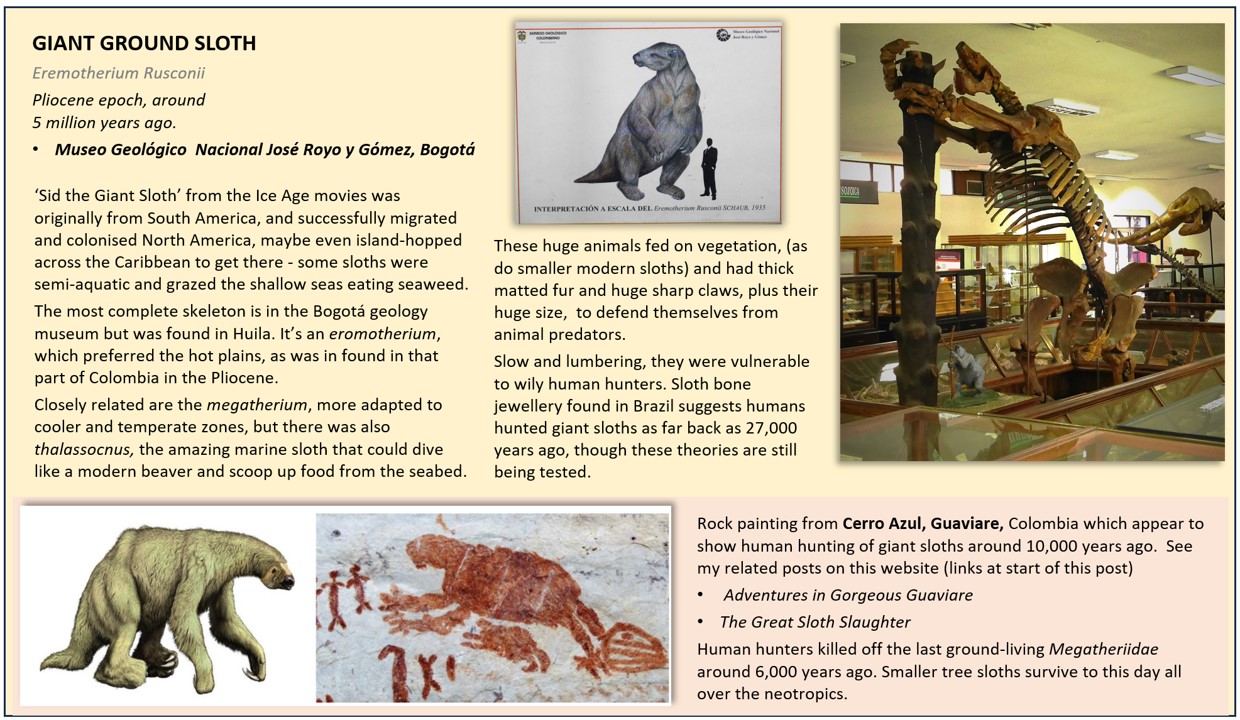

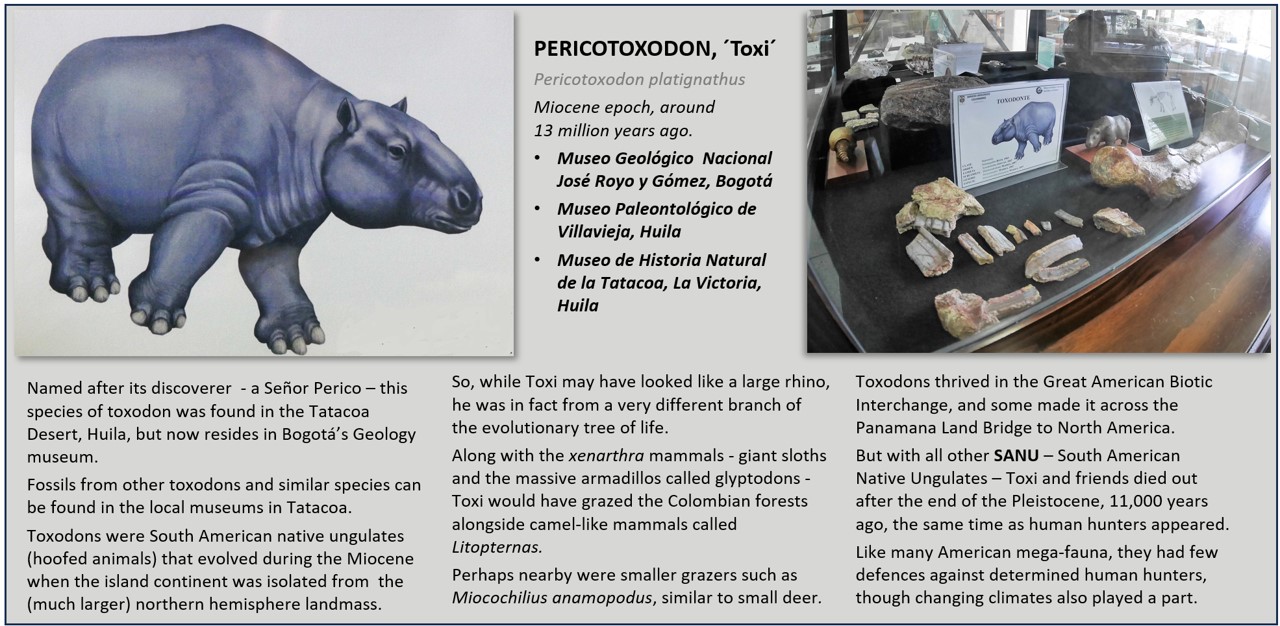

Between 13,000 and 10,000 years ago most large South American animals became extinct, such as the mastodons, glyptodons and giant sloths.

Of course, many lifeforms have become extinct over many millions of years as climate and geography change or catastrophic events such as the meteor that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago. And new lifeforms evolved.

Likewise in South America animals like Snorky died out as their swamps dried up, and new animals evolved or migrated from North America such as the mastodons when the Panama land bridge opened 2.7 million years ago.

The Quaternary Extinction of the late Pleistocene was a global event affecting mostly large land mammals which seems to coincide with the arrival of humans in different continents.

In South America that event started to take place some time after humans crossed from North America through Central America to where is now Colombia around 15,000 years ago, though as mentioned earlier new South American sites are placing human settlements at 27,000 years or even older.

But by 12,000 year ago South America became the continent most affected by the Quaternary Extintion event, losing 83% of its megafauna including giant sloths, mastodons, glyptodons, toxodons, litopternas, short-face bears.Carnivores that preyed on these large animals also disappeared, such as dire wolves and sabre-tooth tigers.

Today the largest land animal in all the southern continent is the tapir at around 320 kilos (710lbs).

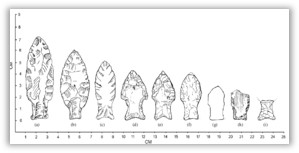

The Fishtail Spearheads

Researchers have found a connection between an abundance of large ‘fishtail’ spearheads that appear in South American archaeological sites at the same time that much megafauna disappears from the fossil record. Human hunters made these large spearheads specifically for big game around 12,000 years ago.

The spearheads disappear from sites after the mega-fauna died off and are replaced with smaller spears and arrows for the smaller animals that survived.

Not used to people…

Humans late arrival in South America meant local megafauna had some naivety to homo sapiens and did not see human hunters as a threat. Perhaps larger animals were easier – or more obvious- hunting targets for humans. and slower to escape. Smaller animals could hide better and evade humans.

Big species also had a slower reproduction rates, and were less able to pass on behaviour adapted to avoid hunters. The biggest mammals that did survive until today did so in extreme conditions: wild llama in cold mountain valleys and tapirs, bears, anteaters, tree sloths, armadillos and jaguars in the deep forest, where many were nocturnal.

Another study postulates that brain size affected survival, as smarter animals had more behavioral flexibility needed to cope with the arrival of Homo sapiens. In this aspect South American mammals such as giant sloths, todoxodons and glyptodons fared badly as – judged on brian size – they were relatively dimwitted.

A change of environment

Probably a mix of factor played a key part in the extinction of megafauna in South America, including human hunting and other indirect human factors; changes in vegetation due to burning, disruption of migration routes etc . Other evidence points to environmental changes such as climate change made some megafauna extinct even when humans were not present.

It’s a controversial subject among scientists, particularly since megafauna ‘kill sites’ are rare. So far, most research has focused on North America which was more affected by climate change in the Pleistocene. The topic in South America needs even more research from palaeontoligists, archeologists and anthropologists.

Late survivors

Some giant sloths did survive on remote islands such as the Antilles until just 4,000 years ago – until humans arrived. Likewise woolly mammoths lived on remote artic islands until a few thousand years ago.

How late did megafauna survive in Colombia? It’s a fascinating question, and one still unanswered, as palaeontologists and archaeologists combine forces to study the impact of humans on these Miocene animals.

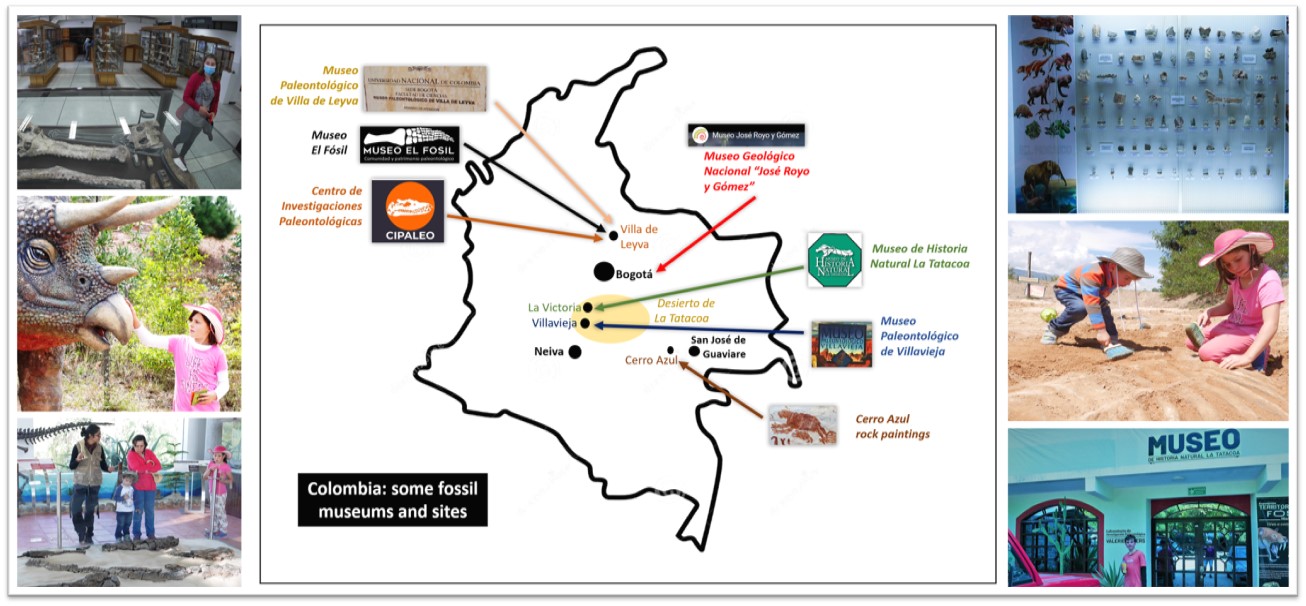

Getting on the Fossil Trail

Villa de Leyva, an historic town 5 hours north of Bogotá, is easy to reach by bus or car and has plenty of hotels and tour compnaies for local excursions, three Fossil museums, a dinosaur park for kids (Gondava Parque). See more details in my posts here:

There are three fossil museums which you can visit in the area,

- Museo Paleontológico de Villa de Leyva

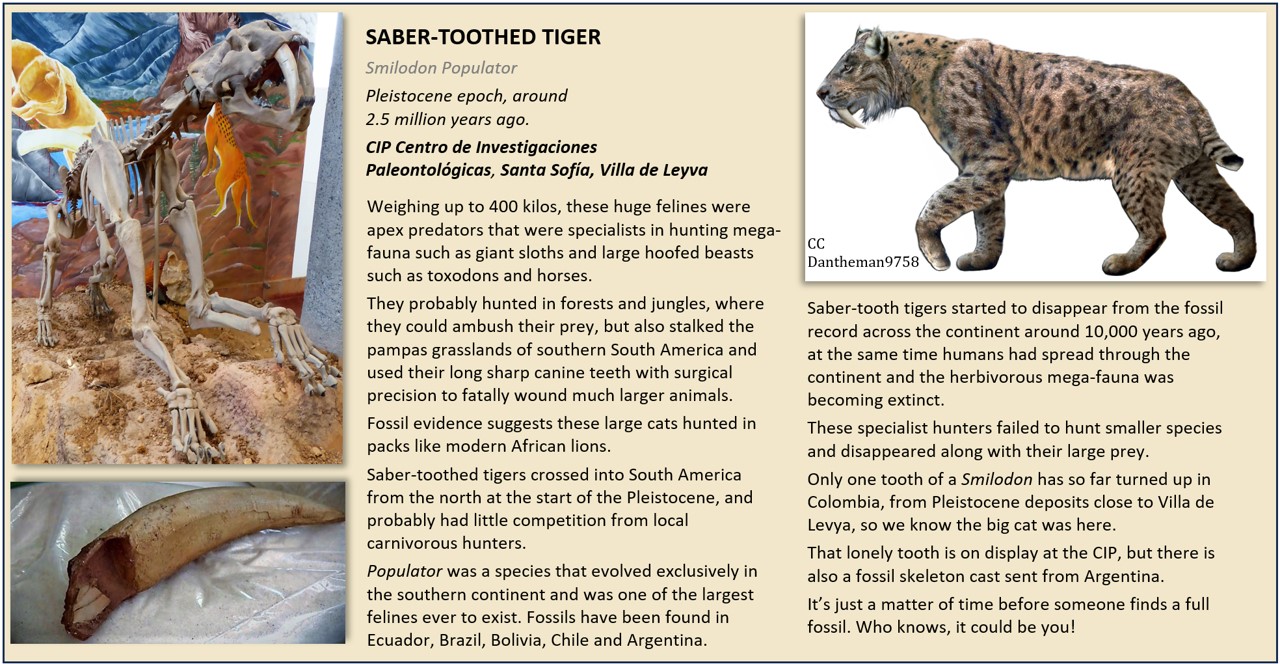

- Centro de Investigaciones Paleontológicas (CIP), with many fossils, a research lab and guided tours.

- Museo El Fosíl, housing the large pliosaur and other fossils.

All are worth visiting, and a short distance by taxi (or on horseback) from the town, but if your time is limited the CIP is best.

For a serious museum in Bogotá you can’t beat the small Museo Geológico José Royo y Goméz close to the Universidad Nacional, it’s open on weekdays and free to go in. There is no sign for it, but you’ll find it on the southwest corner of the Avenida 30-NQS with Calle 53, oppisite the Colsubsidio Sports Center (Diagonal 53 N0. 34 – 53 Bogotá D.C.) Ask the friendly gate guards to sign you in, and show you to the museum. It’s child friendly and you can take photos there.

In the Desierto de Tatacoa (Tatacoa Desert) you can do various tourist activities such as star-gazing, desert hikes, mountain biking etc, it is also a stop on the way to tourist sites in the south of Huila such as San Agustin and Tierradentro.

The base for excursions and local transport hub (by bus from Bogotá) is the small local capital city of Neiva, but you can also find cheap hotels and restaurants and tours in the desert towns of Villavieja and La Victoria.

Villavieja has the small Museo Paleontológico de Villavieja in the town square, it has many fossil fragments some displays but is a bit run down and forgotten.

The much better Museo de Historia Natural de la Tatacoa in La Victoria is also small, but has updated displays and is a base for working researchers – you’ll find a small lab here and some recent fossil finds still in plaster – and the home of legendary local fossil experts Rubén and André Vanegas, who also give guided tours. La Victoria is harder to get to, but worth the effort if you really want to get an idea of the scientific work going on the area.

The Vanegas brothers were locals from La Victoria who started fossil hunting as children, and were so enthusiastic they made many fossil discoveries and grew into keen amateurs then investigators and founders of the museum there, and work closely with top paleaontologists from all over the world.

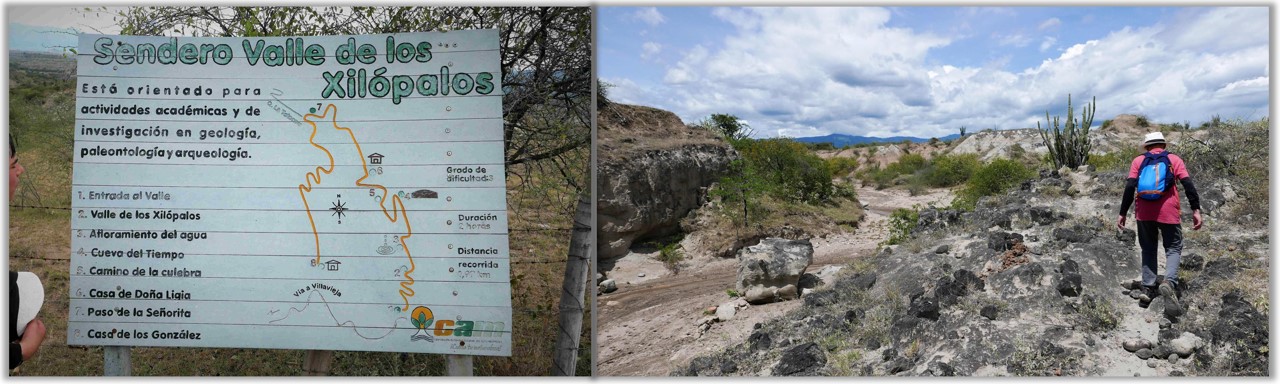

One way to see fossils is to hike in the Tatacoa Desert, particularly in the Valle de los Xilópalos, where you can find fossilised trees in the riverbed. You can take an organised tour from Villavieja or Neiva, or drive there yourself (it’s 30 minutes from Villavieja on the eastern edge of the desert) and pay a small fee to enter alone – take a sun hat and water – or pay for a local guide at the valley entrance.

NOTE: Colombian paleontological heritage is protected by Decree 1353 of July 31, 2018, so removing fossils is illegal.

Useful information...

Some links that might be interesting.

El Bosque de Titanaboa is good technical webite (in Spanish) on some Colombian and South American fossils, particulalry the evolution of mastodons and sabre-tooth tigers.

Fossil Coast Drinks gives a good overview of the how and when of Colombian extinct marine reptiles.