Corruption: do you feel the bite?

by Steve Hide.

This article first appeared in Going Local

in The Bogotá Post, in 2017.

Another day, another sorry saga of corruption in Latin America: the big man using state funds for personal gain with his brothers, sons and nephews on the payroll, while falsely accounting, skimming workers’ wages and ordering white-elephant projects that are never finished. All served up with threats and brutality against detractors or whistle-blowers.

Eventually the big man is investigated, condemned and jailed. But then set free by high-level political contacts. Sound familiar?

Of course. Though you might be surprised that this story goes back the discoverer of Spain’s Nuevo Mundo, Christopher Columbus. As the colonies first governor El Almirante had his devout followers who would follow him to the ends of the known earth. But an equal number despised him as a corrupt despot prepared to torture or kill anyone in his way.

Either way, by 1500 the Spanish Crown had heard enough and despatched investigators. The ensuing report – lost then found in a state archive in Valladolid in 2006 – underscores the perils of sending underfunded and unsupervised conquistadors to far-flung places to with strict orders to send a tax surplus back to Cadiz’s coffers.

Life on the frontier ‘turned noblemen…into rascals and thieves’, to quote James Michener’s Caribbean (a great cheesy read if you have hammock-time in Cartagena). Still, the fact King Ferdinand bothered to send investigators to Hispaniola at all shows that anti-corruption was on his royal to-do list. It also explains why Colón was shipped home to Spain in chains, though (mirroring the fate of future transgressors) he was quickly pardoned by the king and sent back to work.

Colón never arrived in that part of the New World now called Colombia but his legacy of mixing personal self-interest with public office certainly did, along with Spain’s decree-based legal system and centralised bureaucracy that created the need to bend rules just to get things done.

Voting for the ‘least hated’ politico

The result today is a seemingly never-ending parade of corruption scandals gracing the nation’s news headlines and the ever-increasing incredulity of an exasperated population so fed up with their ruling class that pollsters no longer talk of ‘popular’ politicians but rather the ‘least hated’.

‘Now we’ve made peace with the FARC let’s go after corruption,’ is the gist of a national discourse from a population too-long distracted by civil strife. My friend goes further, in his mind decades of conflict was cooked up by a pilfering elite to draw attention from their own crooked ways: ´a smoke screen while they picked our pockets’. The guerrillas were the ‘useful idiots along for the ride,’ he concludes.

Such cynicism is natural when even the government-appointed anti-corruption chief – a lawyer called Luis Moreno – is currently in jail for soliciting bribes from the very politicos he was charged to investigate.

A more optimistic view is that this avalanche of scandals shows corruption is being uncovered, just as the Santos government promised back when it took power in 2010 (tackling graft was the president’s second plank after peace with the FARC).

Most people don’t see it that way. Perhaps this is because of how corruption is measured. Much graft is necessarily hidden so gauging a country’s level is based on the perception of wrong-doing, which in turn depends on media reporting. The more you read about it, the worse it looks. Thus the paradox that a government taking aim at corruption will actually appear more corrupt.

La mordida- the little bite

Another reality of Colombia is that most people don’t need to read the newspaper to perceive corruption: it’s finds them. The bite – la mordida – comes in many small ways from the crooked cop demanding an ‘instant fine’, to the stonewalling bureaucrats in local office needing an incentive to get the job done, to the price-fixing business cartels that push up prices in the supermarket.

For years I was stumped as to why school exercise books were twice as expensive in Colombia as London until, lo and behold, the Cartel de Cuadernos – a price-fixing regime rigidly enforced by the country’s three main suppliers – was unmasked by government investigators. Well, at least it was eventually unmasked (though I did not notice any major price drop in cuadernos).

The job market seems equally controlled. When I suggested to an out-of-work teacher friend that he submit his CV to the nearby high school he replied dolefully: ‘How can I apply when I don’t know anyone there?’. His chances of getting a job there without some friend ‘on the inside’ were so astronomically small he wouldn’t even try.

This touches the perception that without palanca – leverage – nothing can get done, and if you don’t have well-placed friends or family to call in a favour you might just have to pay a bribe. And if you want to do business you have to bend the rules even when (especially when) dealing with the state: a friend who owns a paint shop told me how the local army unit offered her a large order to repaint the barracks but that ‘all the receipts had to be 10% over so the officers get their cut’.

Of course Colombians cannot turn to their political leaders for moral guidance on these issues since the country’s ruling clans are kings of the kickback. The paint shop scenario plays out at all levels, indeed the very political system in Colombia seems set up for skimming through public contract systems that allows elected officials to take their tejada, slice of thepie.

Corruption merry-go-round

There are various mechanism behind this such as the infamous merry-go-round – carrusel de contractos – whereby construction funds are passed down through a series of bogus consultancies, each taking their 10% cut, to eventually reach a bloke with a shovel and a wheelbarrow who actually does the work. Or not. Usually by this stage there is not enough cash left, creating a half-finished white elephant, or the state coughs up more money and the carrousel starts again.

But even if the work is finished there is a high chance it was over-costed with a big boost to the personal coffers of elected mayors, senators and congressmen. Step forward Oderbrecht, the Brazilian conglomerate charged by US courts with the systematic bribing of governments on a global basis and the plat de jour in terms of current Colombian scandals.

And what a juicy feast. By the latest count US$27 million has been paid in bribes to politicians and administrators to serve up contracts for Colombia’s prestigious Ruta de Sol road network. The unravelling web has tangled even ministers from all political hues and tainted President Santos, whose saintly proclamations against corruption – he even made a personal presentation at an anti-graft conference in London last year – are now biting his own back.

Central to that is what actually constitutes corruption. Santos has defended the system of political patronage (perfected under his watch) whereby regional chiefs vie for state funds for their locality. ´Who better to decide what public work needs to be done in their own backyards than the local elected officials themselves?,’ he argues, pointing out that countries like the US and UK operate in a similar way.

This means that senators and congressmen use blackmail to get the funds, demanding the allocation of projects to their region in return supporting reforms the government needs to keep working, a realpolitik which might pass in countries where public works actually get done.

In Colombia where work frequently doesn’t get done – and there is even now an elefente blanco cell-phone app for citizens to photograph and report unfinished structures – most people see a system that simply allows politicians to buy votes, steal money and stay in power.

So why do people vote for los corruptos? The answer is simply that la mermelada (the jam) is spread thin benefiting many families and voters. Mayors, congressmen and senators repay voter loyalty with contracts or jobs which they control by placing ‘their people’ – often relatives or in-laws or clan – in key admin posts, usually including the oversight jobs that should be checking for fraud.

Since most public service staff are on temporary contracts their employment (and their pension, their health scheme and all other benefits which trickle to their families) depends entirely on the election of ‘their person’ to ensure they stay in work. This leads to the remarkable situation after each local election whereby in any given local municipality whole chunks of staff will depart seemingly overnight (sometimes acrimoniously wiping their computer files) while new faces (with connections to the new mayor) roll in.

Of course this new bunch are initially inept so any useful work is put on hold for the next six months as they find their feet including ways to skim as much as they can knowing in five years the axe will again fall – on them.

Breaking the cycle

Will these cycles of nepotism and corruption ever end? Experts say that sufficient laws exist in Colombia to stop corruption but are not implemented. Local government could reduce nepotism on the municipal payroll by moving public workers from temporary to permanent contracts. But no-one does.

Recent laws on transparent bidding should have eliminated bent contracts but powerful contractors bypass this by dictating the terms of the proposal – often in cahoots with the mayor’s office – to ensure only their bid can win. This could be countered by more technical expertise in the preparation of proposals since vague and poorly-costed plans foment graft. Others see education as the key, such as including ethics modules in university business courses.

Others see the initiatives to streamline daily bureaucracy – such as anti-tramite laws and putting popular processes on- line – are reducing both the need and the opportunities to seek or offer bribes.

A good example I came across recently was the Land Registry office where the front desk workers can no longer calculate tax receipts for property sales. Instead, backroom staff – too far away to be slipped some cash to lower your bill – do the maths and send the result to the front desk. It’s small change, but a start.

Measuring transparency and corruption in Colombia.

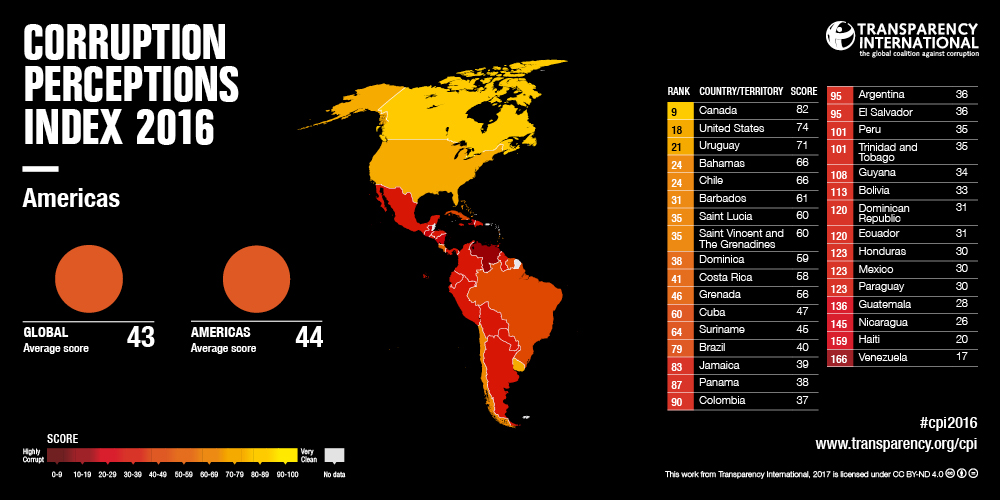

According to Transparency International’s 2016 Corruption Perception Index, (transparencyinternational.org) Colombia scored 37 and ranked 90th (alongside Morocco, Indonesia and Liberia) in the country list, halfway down the list of 176 countries. Regionally it sits at the halfway mark between clean Canada and corrupt Venezuela. The CPI reflects a sample of experts’ perception of corruption (which is not the same as actual corruption).

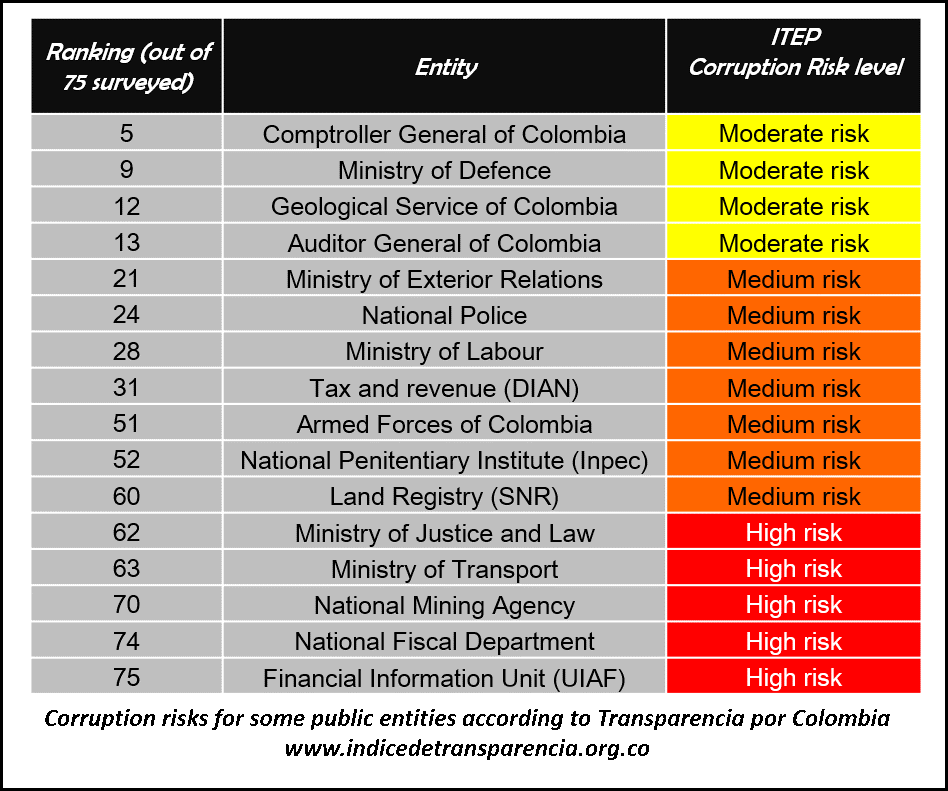

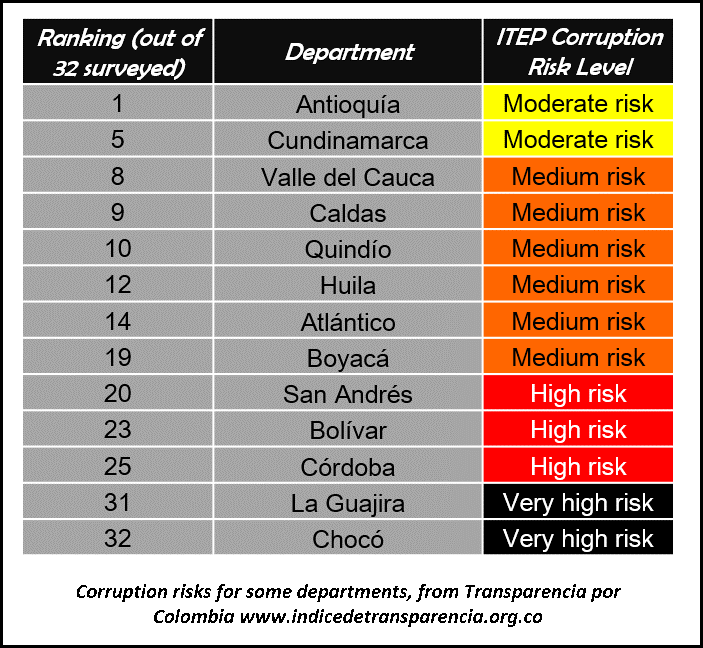

Transparencia por Colombia (www.transparenciacolombia.org.co) is Transparency International’s country chapter with links to an interactive map that pin-points specific cases (www.monitorciudadano.co) andITEP (www.indicedetransparencia.org.co), a public services transparency index that uses survey to rank corruption risks both by territory and by entity.

The ranking reflects the main concern of many Colombians that the very entities tasked with uprooting and punishing corruption – the Fiscalia and the Ministerio de Justicia – are themselves at high risk of corruption. Unsurprisingly the most at-risk departments – Chocó and La Gujira – are also Colombia’s most impoverished.

According to figures from Colombia’s own Inspector General’s Office, corruption costs the country US$7.5 billion every year, which adds up to nearly 10% of the government’s 2017 budget. This means corruption costs each taxpayer US$165 a year – three quarters of a monthly minimum wage.

Some other organisations and government bodies that highlight corruption in Colombia:

- La Comisión Nacional Ciudadana para la Lucha Contra la Corrupción (CNCLC), a government-appointed citizens body that oversees implementation of anti-corruption laws, www.ciudadanoscontralacorrupcion.org

- The government’s Secretaria de Transparencia, tasked with implementing anti-corruption laws, www.secretariatransparencia.gov.co, here you can download the Elefantes Blancos app where citizens can report unfinished public works to social media.

- Another state department dedicated to ‘measure and analyse’ corruption is El Observatorio de Transparencia y Anticorrupción, www.anticorrupcion.gov.co, where you can find on-line resources to fight corruption.

- Online news and analysis sites like www.lasillavacia.com and www.las2orillas.com offer insights sometimes missed by the mainstream media.

- The blog of Bogotá economist Alvaro Pachón, has analysis of the personal tax returns of senior government ministers made public in 2016 after pressure from transparency groups.

Spreading the Jam

Some of Colombia’s corruption scandals

Oderbrecht – a whiff of corruption turns into a proper stench after the Brazilian giant is caught up in Operation Carwash, that uncovers it bribing officials and fixers to the tune of US$27 million to win road contracts, notably in Colombia the Ruta de Sol highway from Bogotá to Santa Marta. This jam spread as far as senior ministers, some of whom now reside overseas. Even the president could become toast.

Reficar –the modernisation ofCartagena’s oil refinery comes inUS$4 billionover budgetafter using contractors which, strangely, have no experience in oil refineries but plenty in the bedroom: this splurge comes with a US$16 million tab for the service of sex workers.

Roads for Prosperity – the presidential plan to improverural roads does bring prosperity to political caciques on the Caribbean coast with large helpings of la mermelada, as revealed by Sillavacia after noticing that all the contracts – no matter where or how long the road – come in at the same cost. Here too we learn how regional senators demand slush funds from central government – the so-called peajes – in return for support for reforms. Call it traffic jam for votes.

If the price is wrong… thenthere is a cartel at work, as in the recent price-fixing revelations of nappies / toilet-paper / fruit / onions / potatoes / school books (you can insert just about any commodity into this list). Remember it’s the free market (free to screw us as they please).

The Community of the Ring – a plot as murky as Mordor as corrupt Colombian cops create a male prostitution ring, complete with ‘male-order’ catalogue, using young cadets to ensnare and coerce politicians. This trafico de influencias leads to allegations of murder, kidnapping and the downfall of a police chief.

Judge dismissed – A senior judge and president of Colombia’s constitutional court, Jorge Pretelt, meets with an oil company director to demand a fat bribe as pay-off to overturn a US$9 million-dollar fine for flouting environment laws. Once unveiled the bent beak refuses to resign claiming immunity from prosecution, but he is eventually suspended (but yet to face jail time).

The Great Córdoba Robbery – Córdoba, Colombia’s cowboy corner, is also its most corrupt with dozens of functionaries, lawyers, judges and senators in jail or being processed for systemic looting of departmental coffers. Then the youthful ex-governor Alejandro Lyons faces fraud charges but makes a dash for the USA to cut a deal and encender el ventildador – turn on the fan – to reveal the dirt on the dynasty families still reigning here.

Corrupt anti-corruption case –the first person outed by Lyons is the country’s senior corruption investigator, Luis Moreno, now in jail facing corruption charges of his own. The fugitive ex-governor claims that the mañoso Moreno took bribes not to investigate him for corruption.

Cartel of the Haemophiliacs – the stateside Lyons might also shed light on Córdoba’s fraudulent list of falsified haemophiliacs through which various senior officials bled the health system for US$20 million. This desfalco happened when Lyons was governor and is now known to have been replicated in other departments on the coast.

Bogotá’s Carrusel de Contratos – a mafia of contractors, lawyers and city officials disappear US$30 million of public money earmarked for Bogotá’s public works including the Transmilenio and fabled Metro through the merry-go-round system of crooked contracting with while each participant takes una tejada de la torta. Bogota’s then mayor (in 2010) Samuel Moreno is jailed along with some contractors.