Did ancient Colombians visit Polynesia?

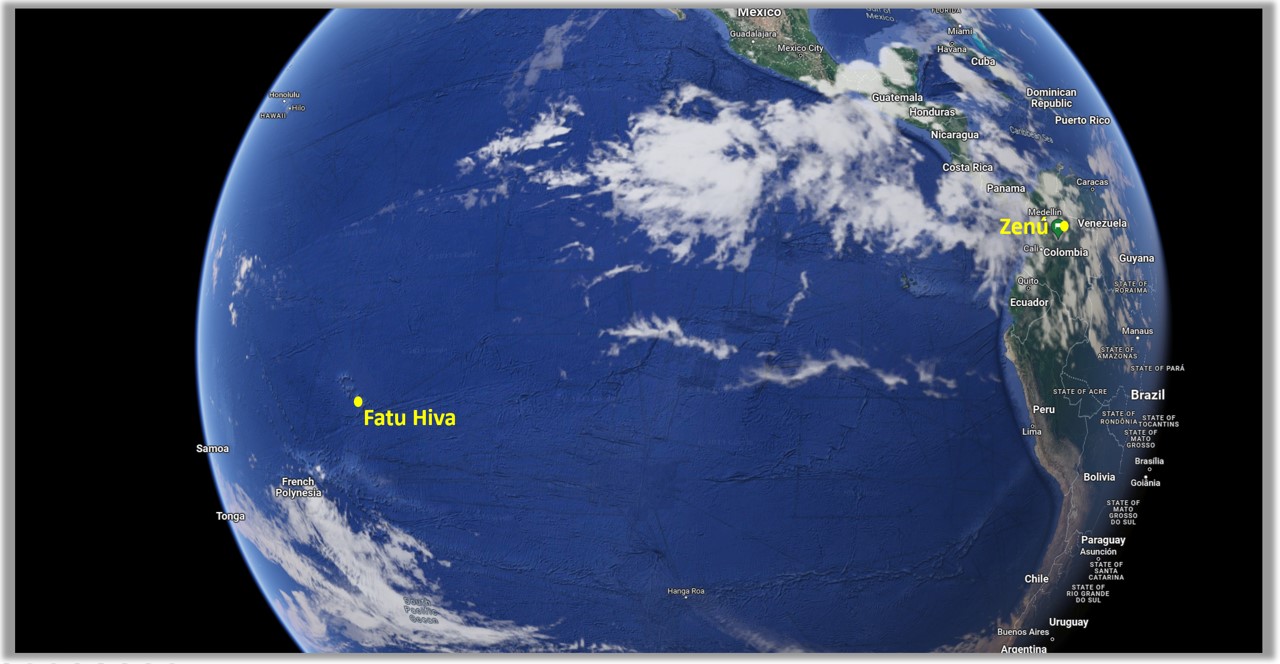

Colombian people living long before the the Spanish conquest met and mingled with Polynesian islanders living 7,000 kilometres away on a tiny speck of an island across the Pacific Ocean.

That’s the amazing conclusion of recent genetic studies is that pre-Colombus Colombians – most probably ancestors of the Zenú people around Montería – mixed up with Polynesians in 1150 AD in Fatu-Hiva, in the Marquesa Islands of French Polynesian territory.

How did they meet? That’s the big question. One possibility is that indigenous Colombians sailed west – or drifted, driven by wind and currents – 800 years ago on a one-way journey that could explain mysterious similarities between Polynesian and South American cultures that have bugged anthropologists for decades.

Posted July 2023. See similar post: Colombia’s Fantastical Fossils – And Where to Find Them

I’ve put USEFUL LINKS at the end of this post…

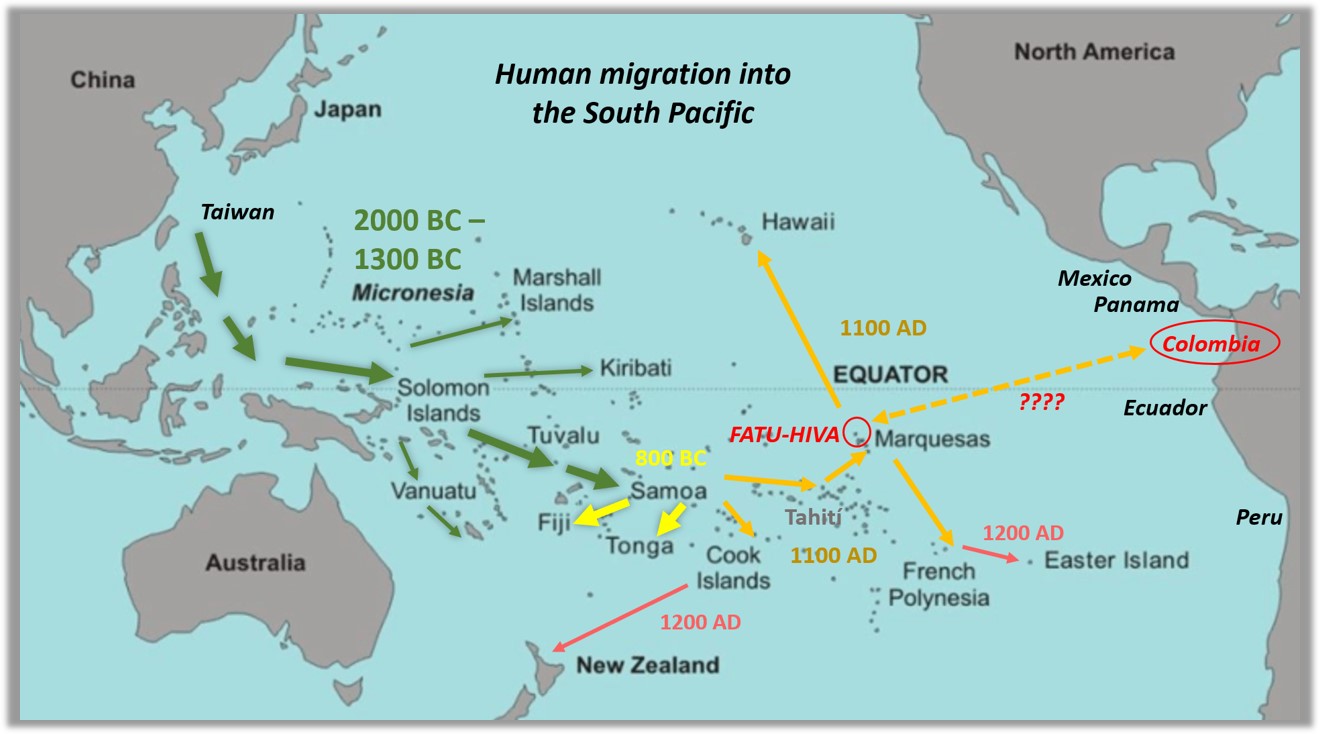

This result comes from a gene study of 807 people from 17 Pacific Island populations and 15 indigenous groups from the Americas that found clear ‘native American’ genetic signals in Polynesian communities in the Marquesas, Palliser and Tuamotu Islands and Rapa Nui (Easter Island).

Fancy math shows that some genetic traits in Polynesians with no European ancestry – meaning the contact between peoples came from before the European colonization of Latin America. Moreover, contrary to previous theories – which placed Peru and Chile as the likely influencers of the Pacific – less-studied Colombian costeños are genetically the most likely to have sown their seeds among the islanders.

That’s a big ‘wow’ on so many levels.

Ancient links across the Pacific

First, remember that any theory on ancient links between the Americas and Pacific Islands has been hotly contested by explorers, anthropologists, and archaeologists for decades. Any serious scientist sailing in that swell of controversy risks getting reefed.

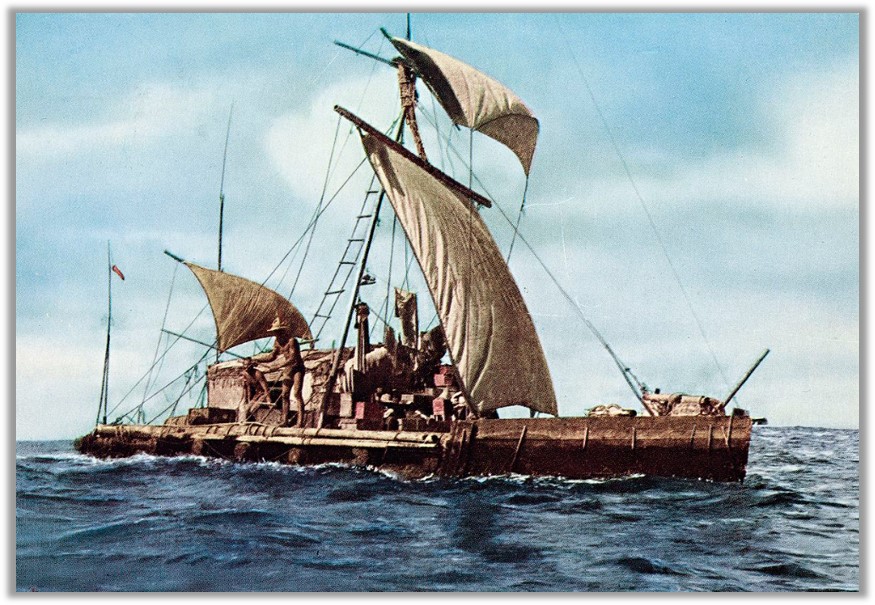

Some anthropologists have long proposed links between mainland South America and the South Pacific, most famously expounded by Norwegian adventurer Thor Heyerdahl, who sailed his balsa raft Kon Tiki from Peru to the Tuamotus in 1947 to prove such navigation was feasible (it was) and to explain how New World foods – gourds and sweet potatoes – were also staples (with similar names!) as distant as New Zealand.

Coincidentally (or not) he had lived for two years as a young biologist in the mini mountain paradise of Fatu-Hiva, an island only ten kilometres across, where he hatched his theories, based on local origin stories of settlement from an eastern mainland.

His subsequent travels in Peru cemented these ideas that Polynesia was settled from South America, and with the voyage of Kon-Tiki, Heyerdahl thought he had sealed the deal.

But many serious scientists disagreed; a heap of other evidence – linguistic, botanical, cultural – that showed that Polynesians originated in Taiwan (like your computer chip) and spread slowly from South-East Asia into the Pacific around 4,000 years ago.

Thor was right – well, a bit

Poor Thor. The scientific community, now backed by new-fangled gene technology, proved ‘conclusively’ that the Norwegian’s sometimes nutty ideas were nothing more than exciting adventure stories. The South Seas were clearly colonized from Asia. Any Native American gene signals found in modern Polynesians were carried there by as part of an admixture with colonial Europeans – explorers, whalers, traders – who played away with the locals wherever they set anchor.

But after years on the scientific naughty step, it seems Thor might have been partly right all along. Just a bit. A new generation of gene analysis tools – and a much wider sample of people to test – have allowed scientists to now find the pre-colonial gene signal that ‘most-closely’ links to the Zenú people in Colombia to Polynesians.

So how and when did the Zenú mix with Polynesians? That’s open to debate. Scientists have a few clues.

On the gene trail

Like detectives, the genes boffins can deduce quite a bit from those strands of DNA.

The Native American gene signal is small, clear and consistent and only pops up in a few islands of Polynesia. The fact it can be found in people who have zero European traces shows it came as a result of direct Native American – Polynesian contact, and before colonization of the Americas.

When parsed with other data, it seems the admixture comes from a one-time contact, and from a very small Native American population. Yes folks, those Zenú and Polynesians only had one party. Though it must have been a good one for the genes to get passed on…

The same Native American signal can be traced back through generations to 1150 AD, and the strongest signal is from the community of Fatu-Hiva in the Marquesas islands. Of course, there are other contenders – such as the Tuamotus – but they’re all in the same patch of ocean.

What’s amazing about that date is that radio-carbon dating of archaeological remains puts Polynesian arrival in the Marquesas at the same date i.e. around 1150 AD.

Party at my place – or yours?

This last nugget of data sets the mind racing: if the Native American – Polynesian contact happened just once, where did it take place? We can imagine several scenarios:

Scenario 1: the Raiding Party.

Polynesian sailors travelled 7,000 kms from the Marquesa islands to mainland South America, landing on the Pacific Coast of Colombia, maybe stay for a while, then met a few local women and took them back to the Marquesas to become part of the Polynesian community.

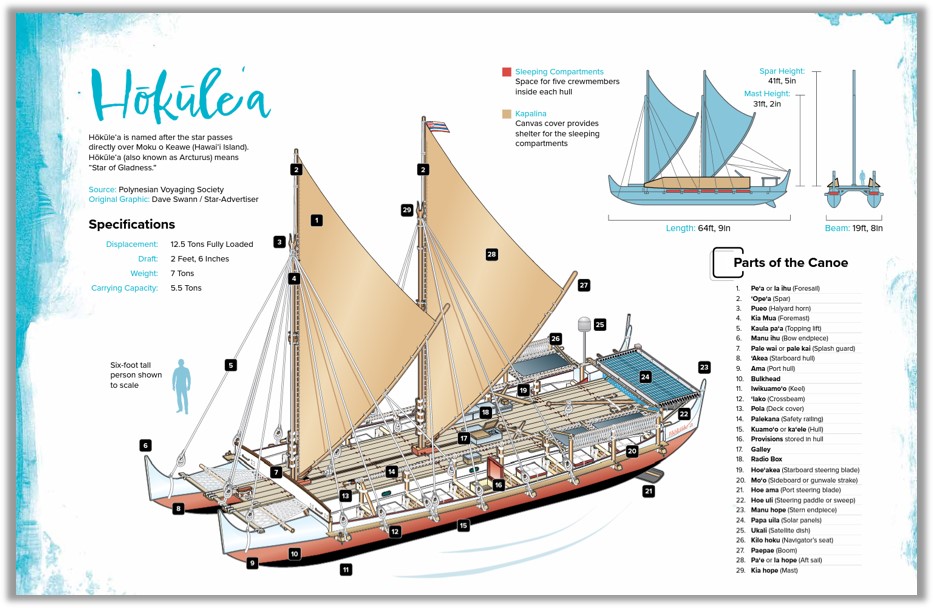

This theory is based on the fact that Polynesians had great navigations skills at the time, having already conquered the vast Pacific Ocean, and had large fast catamaran canoes that could sail affectively against wind and tide, as shown today by craft such as Hokulea, a modern-built large sailing craft capable of criss-crossing the Pacific Ocean.

Also, these Pacific people were in an age of expansion, and in the process of colonizing over 1,000 islands in 2 million square kilometres of vast ocean, the so-called Polynesian triangle. Surely a side-trip to meet some Costeñas would have been feasible.

But there are several holes in this theory. So far, no pre-Columbus Polynesian gene signal has been picked up in Colombia (though it could be found in the future).

It’s also unlikely the Polynesian sailors have stayed such a short time and backloaded Colombians. In this era, according to some literature, Polynesian exploratory voyages were all male crew, and there were taboos against taking women on sea-going vessels (women and children would voyage later after ceremonial preparation).

Another question hanging over the Raiding Party is; if the Polynesians did reach South America, why did they never return? Logically, if there was a raiding party which made it home safe to Polynesia, then they would have come back. The ‘one-contact’ genetic evidence suggests there were no repeat voyages. That’s strange.

Scenario 2: an Accidental Party.

In this scenario, people closely related to the Zenú people currently in north-west Colombia drifted across the Pacific in a large raft to gate-crash a party with Polynesians in the Marquesas. This accidental voyage could have followed a storm or calamity with the vessel.

There is evidence to support this theory: communities on the Pacific shores at this time had large 50-tonne sailing rafts for coastal navigation and trade between Ecuador, Colombia, Panama and possibly Mexico and Peru.

Secondly, currents and wind would naturally carry any raft off the coast of northwest South America that was adrift across the ocean to the Marquesas. In fact, there are some recent examples of modern broken boats doing just that.

We can also imagine that with such regular coastal voyages, the chances of such an accident are quite high. In fact, boats could regularly have been blown out into the Pacific, with most crews perishing, but one lucky team (the ‘one-contact’ crew) making landfall 7,000 kilometers to the west.

Scenario 3: the South American exploration party.

Did Native Americans purposefully explore into the Pacific and one crew make it to the Marquesas? Here we enter Thor Heyerdahl territory, though the Norwegian postulated something a bit different: regular contact between Peru and Polynesian, particularly Rapa Nui (Easter Island), which is off the coast of Chile (and today part of that country).

But in our scenario, we can imagine a one-off one-way expedition setting off from much further north, from Ecuador, Colombia or Panama, by people related to the modern-day Zenú, and making landfall in the Marquesas or Tuamotos.

There are some tantalizing clues that a small number of Native Americans were already living on an island such as Fatu Hiva when the Polynesians arrived in around 1150. For such a community to survive, it would have needed to travel prepared, bringing food supplies, seeds and tubers.

This is where the humble sweet potato comes in: genetic studies show this staple of South America was first introduced into Polynesia around 1100 AD, so around the same time as the Native American – Polynesian genetic admixture. Could the same sweet potatoes have travelled west with the exploration party? Other evidence for this is linguistic, with ‘kumaala’ being the Polynesian word, and ‘kumal’ being used by indigenous tribes of Ecuador.

This cultural interchange suggests the ‘admixture event’ was more than a one-night stand.

Experimental archeology

We’ve already mentioned Thor Heyerdahl’s Kon-Tiki expedition, above, and the modern Hokulea Polynesian sailing catamaran. But he was not the only adventurer setting out to test how ancient seafarers might have used contemporary technology, an activity called ‘experimental archeology’. Other researchers and adventurers, perhaps inspired by Heyerdahl, or by their own observations, made trips which fit more with the new genetic evidence.

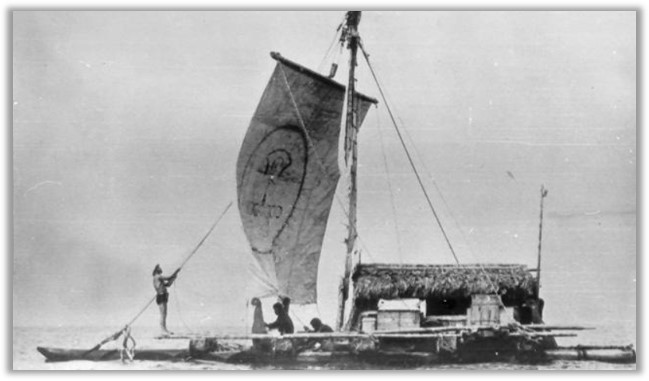

La Balsa raft expedition.

The theory that genes, and potatoes, and the name of the potato, were transferred from South America to the Polynesians suggests a significant cultural exchange – albeit one time, and one way – perhaps best explained by an organized expedition setting off from north-west South America.

To prove that point, another ocean adventurer, Vital Alsar, made an even more daring voyages by sailing rafts covering 9,000 kilometers between Ecuador and Australia in the 1970s.

Largely forgotten by history, the incredible La Balsa expeditions used 14-meter balsa rafts based on pre-Colombian designs described by Spanish explorers in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Alsar’s voyage in La Balsa in 1970 took him and three crew (and a cat) from Ecuador via the Galápagos Islands, Society Islands, Cook Islands, Tonga and New Caledonia to Australia, on a route passing very close to the Marquesas.

So successful was his first trip, that Alsar did it again in 1973 with three rafts and 12 crew, all making it to Australia.

Coastal mariners of north-west South America

Who were these mysterious mariners who made a one-off journey west to Polynesia? Again, we have some clues to competent seafarers living in the area at the time.

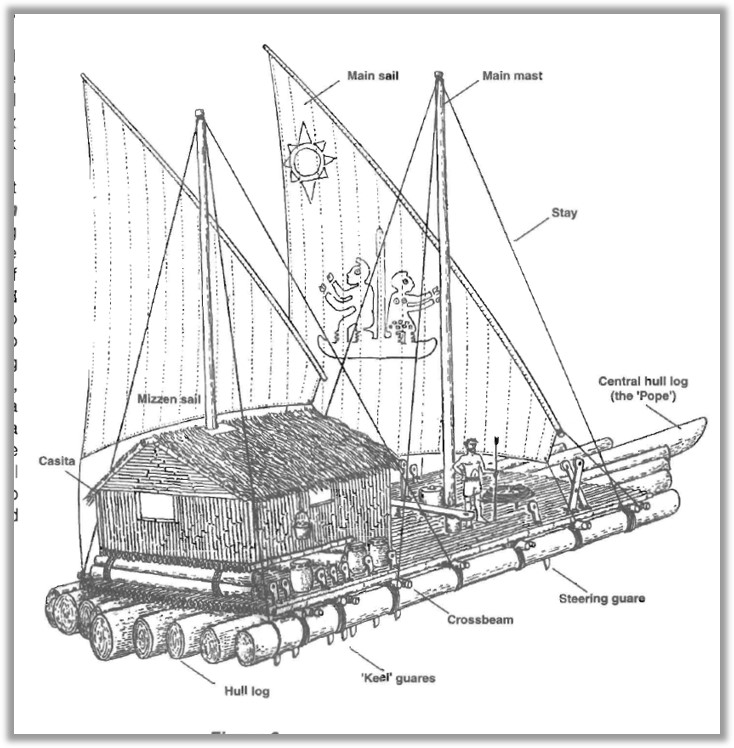

But first let’s look at sails: Alsar’s rafts, like Kon Tiki, were in the form of balsa logs lashed together with a square sail, which is fine for sailing with the wind and drifting with the prevailing currents, with course adjustments made by an intriguing system of wooden keels, called ‘guaras’, that could be pushed between the log slats to trim the raft and control direction.

But perhaps overlooked by both Alsar and Heyerdahl, was the historical evidence that the Manteño culture of Ecuador used ‘fore-aft’ lateen sails to navigate a wide stretch of the South American coast long before the Europeans arrived.

As any sailor knows, for-aft sails are a technological game-changer enabling vessels to sail much more effectively against the wind, and the bare minimum for any seafaring culture wishing to master the ocean, as achieved by the Spanish explorer with their agile caravels, and the Polynesians with their even more nippy catamaran canoes crafted from wooden planks.

Not that the Manteños came up with the complete package; they may have had lateen sails and deep keels, but still floundered along on sluggish balsa rafts which were easy to construct from the super-light timber and bamboo growing on the jungle shore of the Pacific. But with steady winds this was enough to get them thousands of kilometres up and down the coast to Mexico and Peru.

They sell sea shells along the sea shore

Perhaps going back millennia, the Manteño had a monopoly over the spiny oysters (spondylus) fishery. These molluscs had red and white shells that were highly prized throughout Andean countries. The best specimens were found in deeper waters, and the Manteños somehow learned how to dive for them.

Much of the mountain trade was overland, on llama trains, but the Manteño also made sea voyages to sell these valuable shells as far north as Mexico and as far south as Peru. As far as we know, they were the only Pacific Coast culture with this capability at this time.

This ancient trade seems to have given the Manteños some form of protection from the Inca expansion through Ecuador and southern Colombia, since the Incas prized the spondylus for jewellery, inlays for carvings, ground up as red colouring, as offerings to the gods. The coral-like shells were perhaps as form of currency throughout central and south America.

Maybe for this reason the warlike Incas – respecting the Manteños fishing skills – treated them as trading partners, rather than an easy conquest.

An historic meeting off the Ecuadorian coast

But while the Manteños seem to have found peaceful coexistence with the Incas, in 1526 a new bunch of aggressors – the Spanish – under the command of a psychotic pig-farmer called Francisco Pizarro were sailing down the Colombia’s Pacific coast looking for gold.

After some nasty skirmishes with local tribes, the conquistadores holed up on the Colombia’s swampy Chocó Coast – close to the mouth of the Rio San Juan – while one caravel sailed on south captained by Bartolomé Ruiz.

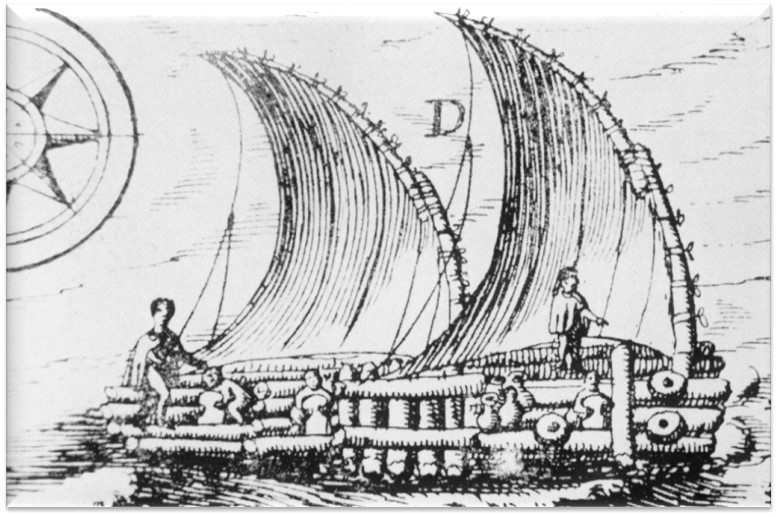

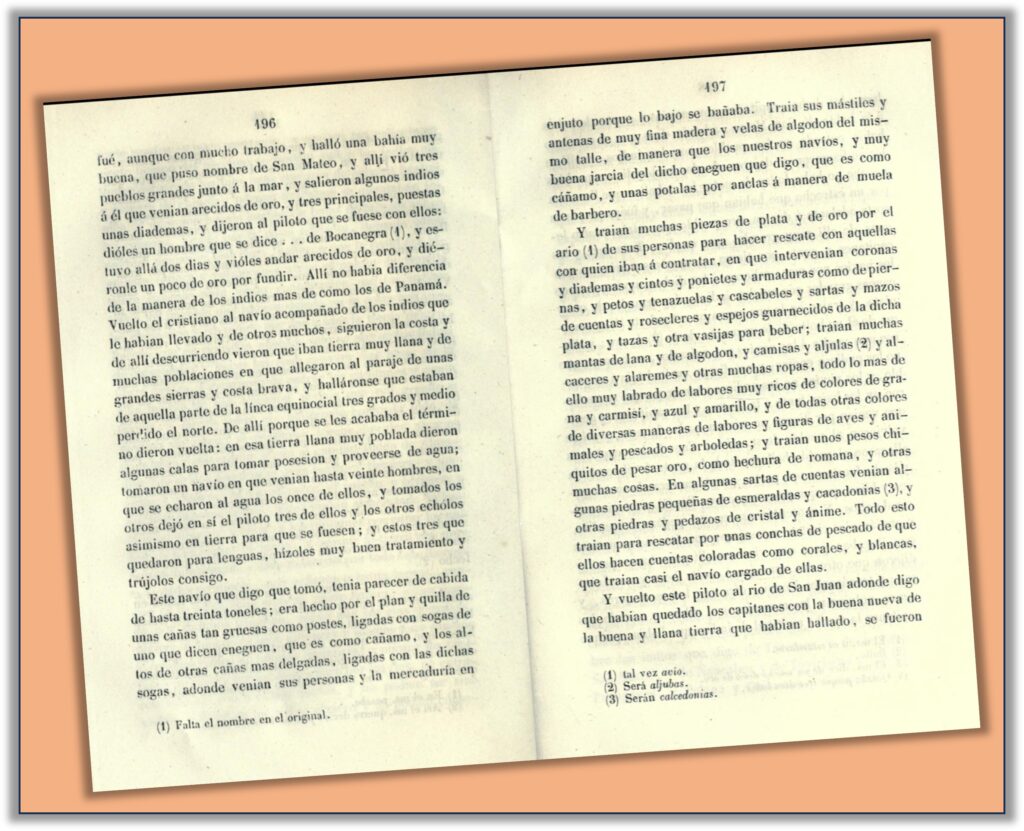

Right on the equator, off the coast of Ecuador, Ruiz’s caravel met with a large sailing raft made of thick logs carrying 20 crew, the details of which are preserved in the Samano-Xerez Narrative, a short document written a few years later, that related how the sailing raft carried fine coloured textiles, beautiful pots, gold, silver, emeralds, and piles of red and white seashells.

The craft is often described as ‘Inca’, but is more likely to be Manteño, and Ruiz describes masteles y antenas de muy fina madera y velas de algodón del mismo talle de manera que los nuestros navíos – that’s to say masts with cotton sails held by poles of fine wood, similar in size and design as ‘our ships’. This means the sailing raft was rigged with lateen sails, like the Spanish caravel Ruiz was skippering.

Voyages of the La Manteña-Huancavelica raft

For every pre-Columbian sailing yarn there is, of course, some white adventurers willing to test it, and the Manteño vessel was faithfully copied – mostly from Bartolomé Ruiz’s description – by Cameron Smith and John Haslett, two explorer-archaeologists who constructed the La Manteña-Huancavelica raft from traditional materials in 1998, choosing to set off from the Ecuadorian port of Solango, the former epicentre of Manteño culture.

They duly sailed their raft north to Colombia, Panama and on to Costa Rica, and, while slow – three knots maximum – it performed well, sailing into the wind as well as European boats of the 16th century.

But the craft was quickly crippled by damage from voracious ‘shipworms’ such as toredo navilis, worm-like molluscs that can munch their way through soft balsa logs in a matter of months, and can evade any number of timber treatments to prevent them. These same critters plagued the ships of Spanish ships exploring these waters, and later the British navy, who took to sheathing their boat hulls in copper sheets to avoid them (hence the English saying that a good plan is ‘copper-bottomed’).

So persistent are these marine molluscs, that Smith and Haslett surmised that the presence of toredo navilis – or a similar shipworm – along the America’s Pacific coastline could been the reason the Manteños used balsa rafts in the first place; shapely plank boats would have been quickly eaten through, while foot-thick balsa logs would last longer and could be easily replaced at pitstops along the coastal route.

This begs the qestion: how did the Pacific Ocean sailors protect their craft from shipworms? Years ago, working in the islands south of Papua New Guinea, I fished a large tiger shark which the local islanders needed for its liver oil, used as a natural treatment to protect boat hulls. Polynesians also used shark oil and wood from certain trees such as breadfruit that was more resistant to the molluscs.

Native American sailors may have adapted differently to ths mollusc threat, preferring large round logs as their hull design.

Enter the Zenú

How do the Colombia’s Zenú people enter the picture? In the genetic study, Native American gene flow into Polynesia predating Easter Island settlement, published in 2020 the scientists find – don’t ask me how – that the Zenú are the closest cluster to the gene markers picked up in the Polynesian admixture from 1150AD.

This is a surprise since the Zenú live today on the Caribbean coast of Colombia – not on the Pacific – in the departments of Córdoba, Bolívar, and Sucre, and are highly assimilated into mestizo culture, having lost their language and traditional ways through intensive colonisation by the Spanish hunting gold in their territory. Today they are known for their textile craftwork and beautiful sombrero vueltiao woven hats.

Historically they were excellent farmers and water engineers, existing for 1,300 years among a vast system of canals and dykes to tame the wetlands and extract the most benefit of the fertile Sinú river valley.

An overlooked corner of Colombia

Often with female chiefs, the Zenú were also excellent potters, textile artists and goldsmiths, and had trading links far beyond north-west Colombia. They mastered the rivers, lakes and swamps of their territory, and the Sinú estuary, the outflow into the Gulf of Urabá, a corner of the Caribbean bordering northwest Colombia and the Panama isthmus.

The gene study authors are keen to point out that the Zenú are, for now, the most likely candidates for that single contact event with the Polynesians, but others might emerge with more genetic studies.

At the time of the Spanish conquest, the Zenú territory did adjoin Embera indigenous communities living in the south of Córdoba, with were in turn in contact with wider Embera communities populating the Pacific Coast from Panama, the Caribbean waters around the Gulf or Urabá. The earliest Spanish explorers identified the Urabá region as a major trading hub between indigenous communities, so it’s likely the Embera mixed both with the Manteño and Zenú cultures.

Even before arriving at the Pacific Coast of Panama, the Conquistador Balboa had been told stories of a major trading hub in the Colombian Chocó, with gold from the western Andes kingdom of Kingdom of Tumanamá (probably Risaralda today) taken to the Rió Docha-Rá (today the San Juan River on Colombia’s Pacific Coast), where large vessels “with paddles and sails” would trade along the Pacific Coast. Balboa never made it to Tumanamá – his expedition was repelled by tribes – but the stories collected by the first Spanish explorers point to advanced trading cultures on both the Atlantic and Pacific coasts of Colombia.

One picture emerging from these scientific studies is how under-studied some corners of Latin America are – for example, Panama, Colombia and Ecuador – compared to, for example, Mexico and Peru.

Communities like the Ecuadorian Manteño are regularly lumped together with ‘Inca’, and any internet search of ‘Zenú’ will turn up pages on sausages, made by a popular Colombian food company of the same name, rather than a culture with 230,000 self-identifying descendants in Colombia today.

Inca and Aztec cultures have hogged the limelight with good reason; they had powerful armies and gold galore. Their conquests were heavily written up and popularised in contemporary literature. It’s worth noting that the Inca empire only spread into Ecuador and southern Colombia in the early 1400s, more than a century after any Polynesian contact with people in that region.

Meanwhile cultures like the Zenú and Manteño have largely been ignored, though the Zenú are one of the largest ethnic groups in Colombia today, with 230,000 descendants, and the Ecuadorian coastal cultures were still building large balsa sailing rafts up until 1925.

The wrong track

Many historians describe Bartolomé Ruiz’s raft encounter as with ‘Inca crew from Tumbes’, a settlement in north Peru, whereas close examination of the Samano-Xerez Narrative shows these people as from the ‘Calangane’, a town in what nowadays is called Salango in Ecuador, and the rafters as Manteños.

These errors put Thor Heyerdahl on the wrong track; he set out from much further south in Peru, with less favourable winds and currents, and used inferior square sails.

But even he made it to Polynesia, as did the heroic Vital Alsar, who did leave from Ecuador (though also with square sails) and made it across the whole Pacific to Australia.

Still, scenarios around the Polynesian and Native American contact around 1150AD are pure conjecture – for now.

Population Y?

And looking back into the mists of time, genetic studies continue to throw spanners in the works, particularly the neat theory that humans spread into the Americas from Eurasia in a nice orderly fashion around 15,000 years ago.

Those pesky geneticists have stumbled on Population Y, a group of Amazon tribes in Brazil with DNA links to Australians and Papuans, with these same markers absent in other Native Americans. When and how were these ancient groups separated?

Then the mystery of the Botocudo; a Brazilian tribe wiped out by European slavers 300 years ago, but whose DNA – extracted from skulls kept in university collections – shows a close genetic tie to Polynesians, with a signal that likely dates back to the pre-colonial era, but after the peopling of the Americas.

Did the Botocudo – Polynesians admixture also point to an early contact across the waves? It seems unlikely – the Brazilian tribe lived in the far east of the country. But so far no other clear answers are forthcoming.

The only thing certain is that the peopling of the Americas is not as simple as first thought; expect more surprises.

USEFUL LINKS

Some scientific sources on genetic evidence of Native American and Polynesian admixture:

- Native American gene flow into Polynesia predating Easter Island settlement

- Paths and timings of the peopling of Polynesia inferred from genomic networks

- Genome-wide Ancestry Patterns in Rapanui Suggest Pre-European Admixture with Native Americans

- The Botocudo Amazon tribe mystery

- DNA links between Amazon people and indiegenous Australians

DNA shows how the sweet potato crossed the sea

This Youtube video from Stefan Milo gives an in-depth overview of the recent genetic discovery and interviews the scientists behind the study

Some explorer and adventureres sources:

- Las Balsas: the World’s Longest Raft Journey

- Vital Alsar Pacific raft expeditions

Polynesian Voyaging Society – Hokulea - Construction and Sailing Characteristics of a Pre-Columbian Sailing Raft Replica

La Balsa de la Cultura Manteño-Huancavilca

Pre-Columbian rafts

Other useful links