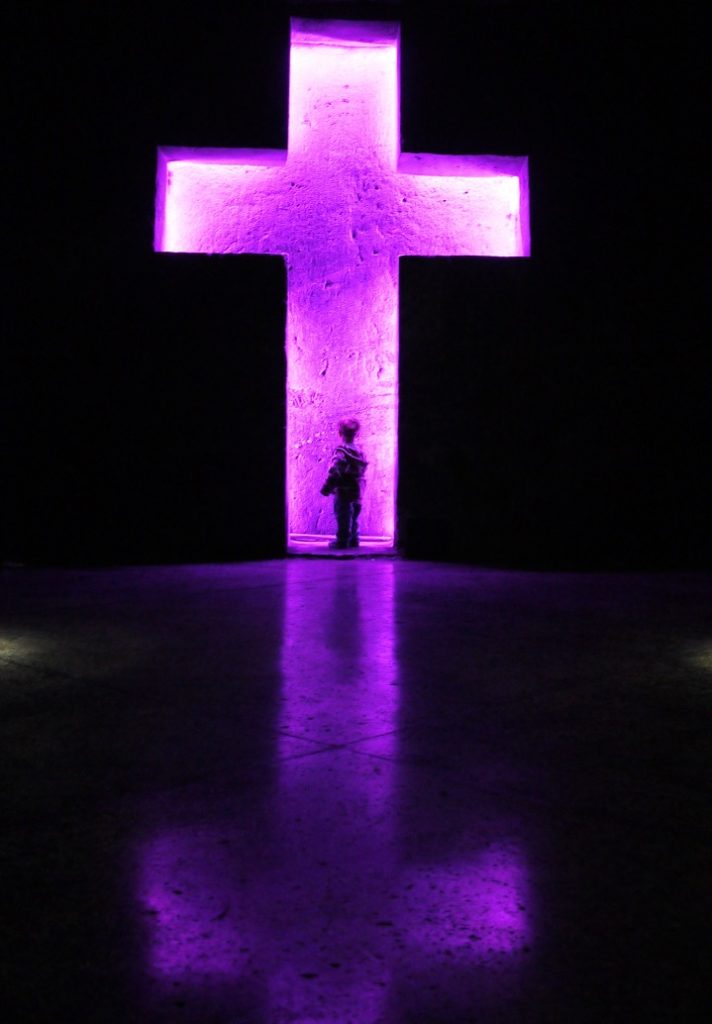

A church for all seasons

The opinion piece printed in the Going Local column in The Bogotá Post in 2018

Related posts:

Two Funerals and No Wedding

Corruption: do you feel the bite?

‘It’s the (narco) economy stupìd’

1538: Bogotá’s conquest

One thing sure to bug me at the end of a long day’s drive over Colombia’s dodgy roads is my wife phoning her mum to announce we ‘made it safely home, gracias a Dios’.

‘Thanks to god! Did you actually see a guy with a flowing beard and white robes behind the car wheel the last ten hours?’ I ask.

Mind you, according to my Colombian friends and family, any car trip – indeed, any journey – is only possible by divine intervention reinforced by constant repetition of si Dios quiere, ‘If God wishes’.

‘We’re going to the cinema later, si Dios quiere,’ says one. ‘The movie will be good, ojala,’ says another, confusing things a bit with Islam through a linguistic remnant from Moorish Spain: ojala originates from Insha’allah, Arabic for ‘If Allah wills’.

My extended family cross themselves before, going to sleep, passing a church, a cemetery, a hospital and at other random moments during the day, and go to mass several times a week. And my own non-belief in a supreme deity is not that controversial because it is simply incomprehensible. Various aunts and uncles ask: ‘why don’t you go to church?’ to which used to reply: ‘because I am an atheist, I don’t believe in god’. This is met with confused silence, so sometimes I just tell them I am a devil-worshipper, which is more believable (at least Lucifer was a fallen angel).

Non-believing is not an option

So for many of my Colombian friends and family, non-believing is simply not an option. The simple fact is that although technically a secular state since the 1991 constitution, religion is deeply entwined in all aspects of Colombia, a country where 97% believe in a Christian god and 80% are self-confessed Catholics.

This fervour stems from the aggressive evangelisation by Spanish colonists, then in the 1800s the Catholic church becoming a pillar of a centralised during post-independence political turmoil. Around the same time country’s education system was wholly managed by Catholic sects.

Two centuries later, not that much has changed. ‘Who else can we trust but the church?’ says one friend, while railing about the general political corruption revealed daily by the news. I hesitantly suggest the church might be much as part of that problem as the solution.

This resonates with another colleague who blames the whole Colombian conflict, past and present, on the church, pointing out that they play both sides of the field from arch-conservative priests blessing the right-wing death squads, to Communist curas taking up guns for the guerrillas. ‘They make a huge mess, then take credit for cleaning it up,’ she adds for effect.

She suggests there are two distinct branches of Catholicism in Colombia: the right-wing conservative strain, and left-leaning Liberation Theology. At the extreme right are groups like Opus Dei, a Freemason-type society tainted by its support for the Franco regime in Spain in the 1970s. Here it embraces some ultra-right politicians and at least one presidential candidate, and recently caused controversy by sponsoring a scientific ‘theory’ from a Bogota medical campus that ‘homosexuality is a disease’.

Then, in the far-left corner, are the ELN guerrillas with their warrior-priests often described as a mix of ‘Jesus, Marx and Che Guevara’.

No room for doubt

All this seems much more exciting than religion of my youth, in the quarter-full chilly churches of small-town England with hand-wringing vicars talk themselves in circles into doubting the very existence of god. In Colombia the Sunday services are standing-room only. There is no room for doubt.

Why so popular? Apart from habit and tradition, Catholicism here takes a flexible approach to its congregation base and pitches a populist doctrine. It’s a church for all seasons.

The same priests who come down heavy on pregnant teenagers – abortion is effectively illegal because of church pressure – give a light touch to philandering husbands. A church which rejects homosexual relationships – and campaigns against gay couple adoption – has warmly embraced murdering drug capos. Why, even Pablo Escobar had his own pet priest with whom he prayed in the same places he also killed his victims.

In my own experience working in conflict areas, my line of communication to the cupola of the AUC, Colombia’s most feared paramilitaries, was via a bishop. And when my boss was kidnapped (briefly) by the guerrillas, who did we call? Why, the local priest.

Then I met with tough-guy Jesuit priests, one guy with a broken nose and cigarette permanently glued to his bottom lip who looked more bouncer than bible-basher. These guys use bullet-proof cars and run safe houses for victims of violence in Bogota and Medellin, but also trek to remote parts of the country where no-one else can, or would want, to go and dole out pastoral care. One recently told me his travails in the Darien jungle where he blessed and buried the bones of souls lost to the conflict there.

In Buenaventura, the Pacific port wracked by the most horrific gang violence, I met nuns who lived in the most dangerous barrios (and sometimes forced to flee from personal threats) and in the small Choco town where the freshly- tortured and killed were dumped in the plaza every day, I knew a priest who bravely read out the names of local gang leaders at the weekly sermon (until one night he too had to pack his bags).

Not all get away. According to La Conferencia Episcopal de Colombia, at least 94 church workers have been killed in action in three decades of conflict, including a bishop and an arch-bishop. The country top tier of Catholicsim, La Conferencia has been a key player in the FARC peace process and is now overseeing the ELN peace talks.

And integral to these talks are the cold hard historical facts of the conflict, often gathered and complied at great risk by frontline priests and nuns. This data forms the basis of hard-hitting reports that lay bare the conflict from the victims’ perspective.

Church can be a thorn in the side of the authorities

For example, in recent years the Centro de Investigación y Educación Popular (CINEP) has openly challenged government rhetoric with its report ‘Yes, Paramilitarism does still exist in Colombia’, compiles data of continuing human right violations and murders of community leaders, which it publishes in a bi-annual report and in recent months has produced in-depth analysis of land-grabs in the Llanos and the ongoing conflict in Tumaco.

Another thorn in the side of the Colombia’s state machinery is the Comision Intereclesial de Justicia y Paz, which through its network of ‘peace communities’ in conflict zones reports a never-ending stream of recent violence against campesinos committed by paramilitaries, their state allies, but also by the ELN and dissident FARC guerrillas.

Both institutions were founded by the Society of Jesus, also called Jesuits, the church’s very own ‘awkward squad’, an apostolic ministry known for supporting the oppressed and poor, and its education and scientific work (they were the first to methodically study seismology) but also for frequently falling out with the church hierarchy. Hence the Society has been periodically supressed during the five centuries of its existence, sometimes branded as subversive and the instigating liberation theology, and often at loggerheads with governments.

So, when Pope Francis stepped out onto the Vatican balcony and uttered the phrase ‘Justicia y Paz’ – a rally cry for the Compañia de Jesus everywhere – it should have been a feel-good moment many Colombians. The church’s main man was now a Jesuit, the first ever to become Pope, and a Latin American to boot.

Five years on the picture is less clear. Sure enough, the Pope’s recent visit to Colombia was a success and with various of my in-laws in tow we chased Francis around Teusaquillo and along the 26th. He puffed the peace process and dissed the naysayers, then surprised all by beatifying a controversial right-wing priest (‘Ha! Playing both ends of the pitch again,’ I commented).

Since then the Colombian Catholic church has got in line with their Jesuit Pope. Many senior church figures are openly backing the guerrilla peace processes which, after all, are the fruit of their own labours. But now we have country-wide elections and the ascendency of Colombia’s right-wing ‘No’ camp, the politicians who campaigned on rejection of the peace process.

So, if the ‘No’ camp wins, the next government will be on a collision course with the Catholic Church? I suggest. My wife scoffs: ‘No politician can defy the church. They’ll have to find ways to agree,’ she says with evangelical certainty. Adding ‘con la ayuda de Dios’ just to be sure. But the tantalizing question remains: would the Church for all Seasons weather the storm?

Catholics versus Christians

In Colombia the Christian Church can be broadly divided into Catholic and Evangelical churches, though the latter are often referred to as Pentecostal or, perhaps confusingly, simply as ‘Christian’.

The rise of non-Catholic sects has been a constant headache for the Vatican in recent decades with successive Popes railing against the rise of Las Iglesias Evangelicas and the loss ofcongregations. A Pew Research Institute report showed that in areas of Latin America by 2014 some 15% of baptised Catholics had switched to the new churches.

In Colombia this switch from Catholicism has traditionally been highest among more marginalised indigenous and Afro-Colombian communities but is now happening in mainstream cities and at least 5,000 Pentecostal churches are now registered nationwide.

Sociologists pin this proliferation on proselyting; new churches can be stricter while simultaneously selling ideals of personal prosperity, while Catholicism is viewed as part of the ‘old’ problems of Colombia linked to the shocking rich-poor divide and status quo. Pentecostal churches also often feature husband-and-wife teams of pastors and preachers, more appealing to young families and a break from the patriarchal Catholics.

Another plus for the Pentecostals is their ability to constantly divide and split into a bewildering variety of smaller churches, often headed up by one charismatic preacher with their own style. Church-goers are freer to can pick what suits them: old or new testament, for example.

So just within one barrio of Bogotá you can find over twenty evangelical churches with names like Iglesia Cristiana Palabra Viva, Casa Sobre La Roca, Christian Church of Colombia, Misión Cristiana Colombia, Iglesia Cristiana Plenitud.

Not surprisingly, with more followers these churches are also now seeing a political ascendency, though they are still far from the reins of power: currently only one Colombian political party, MIRA (Movimiento Independiente de Renovación Absoluta), is openly connected to an evangelical church.

That might change. When President Santos lost the close-run plebiscite vote on the FARC Peace Process in 2016, the narrow ‘No’ victory was swung by evangelical voters in turn mobilised by right-wingers such as ex-president Uribe using social media to conflate religion’s touchstone issues – same-sex marriage, abortion etc – with the guerrilla’s demobilisation.

Now with a looming schism between the Catholic Church and the political right-wing (see main story), the ‘Christians’ are about to enter the arena.