Bogotá’s Colmenares case, a tragic death…

Did Netflix get Bogotá’s Colmenares case correct? Here’s our expectations…and a story on other ‘femme fatales’ tried by media.

First posted in May 2019

…..but where’s the crime?

Luis Colmenares,a young vivacious student from a wealthy family, was found dead in a storm drain tunnel in Virrey Park, Bogotá, in 2010, after nightclubbing at an uptown Halloween party. Later three student friends were accused of his murder, or being part of a plot to kill him and cover it up. After lengthy court trials and controversy the case was closed in 2017 after a judge their was no evidence of murder, the death was likely an accident, and the students absolved.

I’ve been following the case over many years, and wrote some short articles on it which I repeat below. The case was turned into a Netflix Crime Diaries series (A Night Out) first out in May 2019, re-opening the controversy and old wounds for the grieving family and accused students.

Most Colombians believe otherwise. Most of my friends are certain there was a murder, and a cover-up, with rich and powerful political families tussling over who can bribe the highest or dig deepest into their bag of dirty tricks to win their day in court. And being Colombia, with its history of corruption and weak (and buy-able) justice, it’s easy to believe a conspiracy.

OK, so I don’t claim any inside knowledge of the case or insights into criminal proceedings. But having read many articles, and seen interviews which represent both side of the story – both with the Colmenares family and fiscal prosecutors, and the defence and defendants accused or murder – I strongly believe there was no crime committed, and the accusations against the student friends were false. Why? There was no motive to kill Luis. At least not by the three accused. And compelling circumstantial evidence – such as their phone records and proven movements on the night – showed there was no opportunity for them to carry out the killing.

Many people do believe Luis Colmenares was murdered. And perhaps the bereaved family have every right to shout that from every rooftop. But in my opinion, analysis of the fact shows it was an accident.

And ironically, perhaps, the ‘travesty of justice’ decried by many commentators on the case was a cover-up to murder, but rather accusations based on false testimony (and paid-off fake witnesses). That’s also a serious crime which up-ended the lives of innocent people who loved and cared for Luis, people who tried to help him on the night of his tragic death.

My first article Colmenares: Where’s the Crime? in the The Bogotá Post in 2019 looks at the upcoming Netflix series and how we expected it to play out.

The second, older story was The Witching Hour printed in The City Paper in 2017, where I drew parallels between the Colmenares case and two other famous miscarriages of justice where female ‘killers’ were largely condemned by media: Lindy Chamberlain and the infamous ‘dingo baby killing’ in Australia; and Amanda Knox, the American student whose unfortunate housemate was murdered in Italy.

Colmenares: Where’s the Crime?

Netflix’s take on the Luis Colmenares case hits the screens this week. Will it do justice?

First printed in The Bogotá Post in 2019

Who was Luis Andrés Colmenares? The 20-year-old student at Universidad de los Andes died after falling into a flooded culvert in Bogotá’s Parque Virrey after a Halloween party in 2010.

So how did he die? According to a defining court verdict in 2017, the popular student, who had been whooping it up with his friends in a night club close to the park, drowned after falling into the fast-flowing channel – swollen by heavy rain on the mountains above – and his body carried deep into a storm-water tunnel.

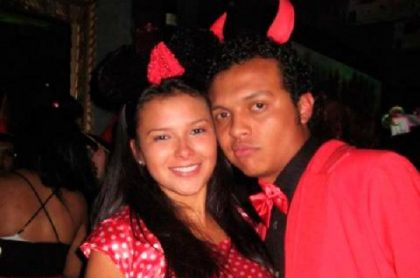

Did he jump, fall, or was he pushed? There’s the rub. While the initial investigation concluded he jumped or fell, a year after his death, his family insisted he had been murdered. The case was reopened, the body exhumed, and a second autopsy done. Suspicion fell on his estrato–seis student buddies and a female close to his affections, Laura Moreno. Like Colmenares, Laura was the scion of a wealthy family. She also had everything the public yearns in their femme fatales: youth, wealth, striking good looks, political connections and a very calm exterior.

So it was murder then? Many Colombians think so. In the eight years following the tragedy, drawn-out court cases and sensationalist media sowed seeds of doubt to the accidental death verdict. The prosecution claimed improbability that a healthy young man could die in a shallow drainage channel. He must have been pushed, went the argument, or more likely beaten up and thrown in. Maybe by one of Laura’s male friends, or her personal bodyguard. The fact that firemen called out to search the culvert an hour after he went missing had found nothing added weight to a theory that he had been killed elsewhere and his body dumped there to fake an accident or suicide.

Forensic experts then claimed to find evidence on his exhumed body that showed beatings, and multiple injuries impossible to come from a simple fall. The hunt was on for the culprit.

Laura Moreno, as a close companion that night, the object of Luis’s desires, and with a tough-guy ex-boyfriend in tow, was in the spotlight. By her own account she was also the last person to have seen him alive, having chased after him into the dark park to help him through a personal crisis triggered by a long night drinking.

Was it clear then? Not really. Now started a power-play between influential families – the Colmenares clan and the wealthy accused’s – with Colombia’s top lawyers and most ruthless prosecuting attorneys all willing to leak any juicy detail to a febrile media, and a tweeting, youtubing public galvanised by this fight of elephants. And trampled in the grass beneath was Laura Moreno, who became nationally vilified as an arch-priestess of evil who had her wayward friend killed and then used her family’s power and influence to wriggle out of a murder charge. Surely this real-life telenovela had found its villain.

But then it all stopped: Well, yes. Unfortunately for the misogynistic masses who wanted to see Laura get sent down, in 2017, the whole prosecution case collapsed under the weight of its own inconsistencies. Fresh analysis showed Colmenares’ injuries were actually consistent with an accidental fall in the culvert. More to the point, evidence of ‘beatings’ from the second bungled necropsy was in fact looking at tissue damage from the first autopsy. Examination of lungs and airways showed he died by drowning.

Furthermore, rainfall and water-flow rates from the culvert on the night the student died – data covered up by the prosecution – proved the flow had force enough to carry a person into the tunnel. In fact, actual tests in the culvert with dummies showed just that. Then it was revealed that the first firemen on the scene – on the night Colmenares disappeared – had never actually searched the tunnel. So the body was there all the time.

And careful examination of the timelines of known locations of the students, their phone-calls and actions showed no time for them to have caused or witnessed a murder or found the opportunity to cover it up. Worse, prosecutors were found to have paid off criminals to act as fake witnesses to back the murder theory. Final verdict: accidental death.

So why is there a Netflix series starting this month called ‘Historia de un Crimen: Colmenares’? Good question, and one that Laura Moreno’s lawyer is also asking the streaming giant. I mean, if the death was an ‘accident’ then surely it can’t also be a ‘crime’.

Does this mean Netflix knows more about the case than Colombian justice? Unlikely. In fact, it seems that no-one connected with the real-life case – least of all the acquitted accused and the family of Colmenares – were consulted for the script. And Netflix is careful to say ‘a series inspired by real events’. Meaning bits are made up. And, so far, we’ve just seen a trailer, which – like the series title – strongly suggests foul play. But no-one really knows how the plot will play out until the series goes live.

Could the Netflix series reboot the legal case? In fact, the case was never closed: the Colmenares family, still believing strongly that Luis was murdered, had appealed the 2017 ruling. Meanwhile the accused student friends of Colmenares have tried to move on with their lives and are furious at being dragged back to the spotlight. But even the Colmenares family are dismayed with Netflix’s intrusion in their grief, having no idea how their personal crisis will be portrayed on screen.

So in Netflix’s ‘Crime Story Colmenares’, there was no crime? Not unless you count false accusations, obfuscation of facts, dirty tricks, serial leaking, inept rescue services and trial by media: acts all contrary to normal justice procedures. Then the ‘victim’ was Laura Moreno. If Netflix did their homework, then that’s the twist in their tale.

Colombia’s “Witching Hour”

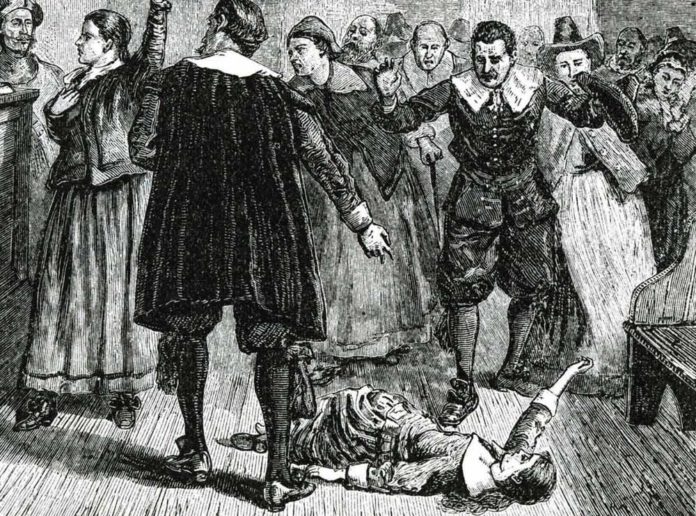

Throughout history society has demanded its ‘deadly females’, even if it has to invent them. Here we look at three cases where women were pilloried by public opinion, then freed after gruelling legal battles.

First appeared in The City Paper in 2017

Lindy Chamberlain, Amanda Knox, Laura Moreno. Three women from different times and places but all accused of murder with the crushing weight of forensic science, trialled by media, crucified on the altar of public opinion, pilloried by (at best) incompetent and (at worst) devious investigators, all the time eclipsing any male co-accused, and even after a final acquittal continuing to be branded “sluts”, “zorras”, or “bitches” by a disbelieving mob unhappy with the outcome of a story arc as old as Jezebel.

Witch hunts are alive and well today. Society loves nothing more than a female killer to hate, and if it can’t find a real one, it invents one. And once it has one, it never lets go.

Lindy Chamberlain lost her nine week-old baby Azaria when the infant was snatched by a dingo (a type of wild dog) from the family tent during a camping trip to Ayers Rock in Australia in 1980. Immediately after the disappearance, aborigine trackers had found signs of dingos close to the tent and drag trails, but this evidence was suppressed by prosecutors who instead pursued the theory that the Chamberlains had murdered and buried their baby daughter.

This grew from the coroner’s doubts that a dingo – quite a small dog species – could carry off a baby. The ensuing media hype focused on the mother, rather than her husband Michael, and the fact that she kept her composure in public and never seemed to fulfil the archetype of the ‘grieving mother’. This fuelled the notion that the Chamberlain family, who were Seventh Day Adventists, had ritually sacrificed their daughter. Newspapers claimed that the name ‘Azaria’ meant “sacrifice on the wilderness” and that, yes, Lindy Chamberlain practiced witchcraft.

The dingo is Innocent?

The case gripped Australia with the narrative of the ‘noble native dog’ versus ‘twisted humans’. No-one believed this cold-hearted mother who couldn’t even cry over her own dead daughter. Everyone sported T-shirts saying The Dingo is Innocent.

But those of us living and working in the real Outback at the time had a different perspective: working on cattle stations I regularly heard the yap-yap-yap of dingos pulling down terrified calves at night. If dingos can tackle 20-kilo calves then a baby is just a snack. Some experts stated the same, but their voices, like the infant, were lost in the wilderness.

So no-one was too surprised when forensic experts found a spray of human infant blood in the front car well: the place her mother allegedly cut her throat before Azaria was buried in the vast desert. Lindy, now the most hated woman in Australia, was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Roll forward 25 years to the age of Internet and the world is sensationalised by American Amanda ‘Foxy’ Knox on trial in Italy after her English flatmate is found murdered. Here, foul play was never in doubt, but who did it? A male suspect was quickly arrested and charged, but prosecutors were convinced that Knox was also to blame. Why? She was seen smiling just days after the incident so she must be guilty. The media set out on a feeding frenzy of salacious tit-bits from the private life of this possible killer (while virtually ignoring the male suspects).

Spring break on steroids

A picture emerged of a Spring Break-on-steroids sex-romps-gone-wrong that led to a grisly murder. But it is unlikely that this character assassination led by the media, aided and abetted by ambitious prosecutors with a large sidedose of anti-Americanism, would have sunk Knox until, step forward, the expert forensic evidence that linked Knox’s DNA to the victim’s clothing. Not only was Knox condemned to 26 years in jail, she was indicted for ‘slandering the police’ after speaking out of her mistreatment during interrogation. Two other men were also found guilty of the murder and sentenced to 24 and 16 years.

Meanwhile in Bogotá, a year after Knox was jailed in Italy, a late-night Halloween fancy-dress fiesta among affluent students took a fatal turn: at 3am on October 31, 2010, Luis Colmenares was reported missing by his friends under suspicious circumstances close to a drainage channel that runs under Parque Virrey.

The 20-year-old student had been partying hard but got upset and separated from the group. What happened next is the subject to much speculation, but 16 hours later his lifeless body was found deep in the culvert. The death was initially explained as a tragic accident, or even suicide, but a year later the victim’s mother had a dream he had been murdered. The case was reopened, the body exhumed and a second autopsy performed.

The twists and turns of this supposed murder case, which has gripped Colombia for years, focused on the tangled relationships of Colmenares with his cohort of estrato-six buddies, and particularly, his closeness to Laura Moreno, whom he coveted as a girlfriend. Moreno, like Colmenares, was the scion of a wealthy and connected family and had everything the public yearns for in their fantasy of femme fatales: youth, money, striking good looks, political connections and a very calm exterior.

The prosecution was based on the improbability of a healthy young man falling or throwing himself into a shallow drainage channel and dying. He must have been pushed, went the argument, or more likely beaten up and thrown in. The fact that firemen called out to search the culvert an hour after he went missing and found nothing, added weight to the theory that he had been killed elsewhere and his body dumped in the ditch to fake an accident or suicide.

Forensic experts then found evidence on his exhumed body that showed beatings, and multiple injuries impossible from a simple fall. The hunt was on for the culprit. Laura Moreno, as a close companion that night, the object of Luis’s desires, and with an angry ex-boyfriend in tow, was in the spotlight. By her own account she was also the last person to see him alive, having chased after him into the dark park to help him through his personal crisis triggered by a long night of drinking.

Fight of elephants

Onto this fertile ground of conjecture stepped some of Colombia’s top lawyers and most ruthless prosecuting attorneys, all willing to leak any juicy detail to a febrile media, and a Tweeting, You-tubing public galvanised by this fight of elephants. One thing the forensic experts insisted was that the death was down to human aggression. Someone had beaten Colmenares. An ex-boyfriend of Laura was arrested, then released. But as the last person to see him alive, even if she did not deliver the blows, Laura was presumed to be behind it.

Like Lindy and Amanda before her, Laura stepped into the shoes of the female killer pre-judged by a misogynistic media bent on her downfall. And, as with her predecessors, she stood accused with the full weight of expert evidence against her.

She might at some point have found consolation in the final outcomes of these other witch-hunts. In Italy, in 2011, Amanda Knox’s salvation came from the same ‘technical’ source that condemned her: human DNA found on clothing and a suspected weapon. A court review found bungling by police at the scene of the crime that cross-contaminated multiple DNA source rendering most samples inconclusive. Only one suspect – one of the males also sentenced for the murder – was present in quantity, reinforcing his conviction. Knox was acquitted and freed.

Lindy Chamberlain’s break came after four years in prison when her baby’s clothes were found next to a dingo lair close to where the family had camped years before. Then, fresh analysis of the ‘baby blood’ in the car turned out to be an anti-rust compound, common in all Australian cars. Why, you might think, did the initial “experts” not check other cars before giving the damning conclusion of ‘baby blood’ in the Chamberlain’s car?

Lindy was released from jail in 1988, but it would take another 24 years of public excoriation before the Australian courts finally ruled off death by dingo and apologised to Chamberlain for the long-running miscarriage of justice. Oh, and ‘Azaria’ means ‘God’s help’.

Case picked apart

Back in Colombia, it would take six years before Laura Morena was absolved of complicity in the killing of Luis Colmenares. Unlike Lindy and Amanda, Laura never went to jail, but rather faced constant public and media vilification and personal threats during which her young life was derailed. The legal ruling came in February when Colmenares’ death was declared an accident by a female judge who picked apart the prosecution’s case with surgical detail.

Fresh analysis showed Colmenares’ injuries were in fact consistent with a fall in the culvert. More to the point, evidence of ‘beatings’ from the second autopsy was in fact looking at tissue damage from the first necropsy. Examination of lungs and airways showed he died by drowning.

Furthermore, rainfall and water-flow rates from the culvert on the night the student disappeared – data covered up by the prosecution – proved the flow had force to carry an unconscious person into the tunnel. And the first firemen on the scene, it turns out, never properly searched. The body was there the whole time, and careful examination of the timelines of the known locations of the students, phone-calls and actions, showed no time for them to have caused or witnessed a murder. Even less find the opportunity to cover it up.

Under this scrutiny the prosecution case looked flimsier than ever, but has Colombia taken this latest ruling to heart? Can Laura Moreno regain her life? Not likely. The family of Colmenares have appealed to try to once again bring a murder case before the courts. Accord- ing to a recent media surveys, more than 70% of the public still believe that Laura and her friend Jessy Quintero are implicated in the student’s death, and that their wealth and political connections bought them their freedom. “Justice is a joke,” is the Twitter meme of the month.

The irony is that the justice system did in the end get it right, but along the way, the public lost trust in due process. The other irony is that Laura Moreno’s actions on that rainy night were driven by care and compassion for her wayward friend, but in that crazy time – the witching hours – his life ended and hers became undone.