Colombia’s Catatumbo: The Never Ending Storm

A quick visit to Catatumbo, Colombia’s conflicted corner, brings President Petro’s troubled Total Peace plans into sharp relief.

Posted in February 2025.

See related posts

Storm photo Fernando Flores

In Tibú, a sweaty town in the Catatumbo region of northeast Colombia, heavily-armed soldiers shift their feet on a street corner, nervous eyes darting left and right.

Meanwhile, two blocks away in the leafy main plaza, two men dismount a motorbike, draw their pistols and without a word spoken shoot dead a man selling ice-creams. Just as quickly, they’re gone. People scream and scatter as blood pools on the pavement.

We can’t say for sure who killed the vendor. Or why. But chances are it relates to conflict waged between two armed groups vying for territory, cocaine, gold mines and smuggling and human trafficking routes to nearby Venezuela.

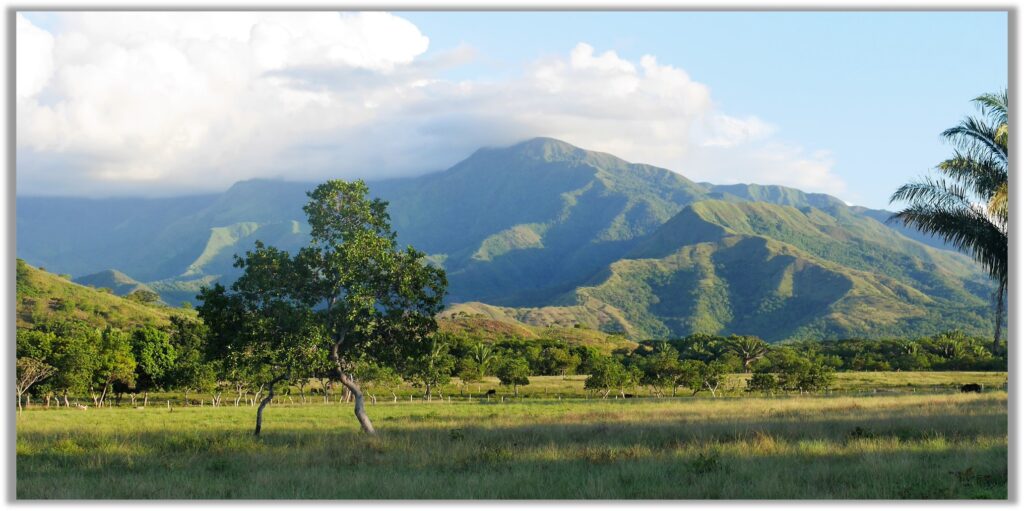

It has escalated into open combat between the ELN and FARC 33 fighters across Colombia’s prime coca-growing region, spread over 5,000 square miles of jungle and steep green hills, wedged into a corner with Venezuela.

Although the official figures state 57 deaths, there is growing testimony of hundreds killed, including civilians, and many more injured. At least 50,000 persons have fled to towns and cities, and many more are confined by fear in their farmsteads.

Stories emerging from the bush are horrific; campesinos hunted like animals and families kidnapped and beaten.

And it’s a situation Colombia’s left-leaning President Petro seems powerless to stop, despite his much vaunted Paz Total, a total peace plan, offering generous negotiation terms to an array of armed groups that have kept the country in internal conflict over decades. So far, it’s failed.

Window Dressing

“The army is here, but the soldiers do nothing,” says a man in the main plaza of Tibú. “It’s just for show.”

Stung by the crisis, Petro has sent fresh troops to the area and ordered a “ring of steel”. But on our drive through the Catatumbo, all the military checkpoints were empty. In the town itself soldiers seem mostly stationed outside shops on the main drag.

Word on the street is that the ELN, Colombia’s oldest guerrilla group, is still very much in charge, and just west of the town the guerrillas have set up multiple retenes to control their heartlands, and hung their red and black banners in villages all over the rural areas.

I’ve driven here from Bogotá, a two-day journey, over mountain passes and down deep canyons, with the last part along the troubled border with Venezuela.

Now I’m sitting in the leafy main plaza eating churros and watching families stroll by in the warm night, little suspecting that the ice cream vendor will be killed just metres away the next morning.

Soon after sunset, armoured vehicles park up outside the church, and few soldiers spill out, but after a quick foray they’re gone.

In living memory, Catatumbo has never been at peace. But the current fighting reflects something different, and new: a bloody chapter with civilian families in the crossfire.

What changed?

Bring Out the Bodies

“Trouble was brewing two months back, in December, but the news media were too busy with Christmas to report it,” says my new friend in the plaza. “Things really kicked off in January.”

News crews did arrive after a family of four, including a 10-month-old baby, were machine gunned in their car outside Tibú on January 15. Three of the family died.

The father ran a Tibú funeral home which, at very high risk, collected bodies for burial, bodies which the guerrillas on both sides wanted unaccounted and uncounted: hundreds were rumoured left to rot or informally buried in remote parts of Catatumbo.

Why the owner of the funeral home and his family were targeted is still not clear, though the prevailing theory was that he disobeyed orders from guerrilla groups not to collect the dead. His whole family paid the price..

All sides had an interest to cover up the scale of the killings: both the FARC 33 and ELN guerrilla groups who were engaged in on-off peace talks with the state. And the Colombian government, whose leader President Petro, who has staked his political legacy on an everything-everywhere-all-at-once peace plan, coined Paz Total.

Paz Total was designed to reduce violence in rural communities by giving all major armed groups a seat at the table. It didn’t work out that way.

Signs of the Times

Soon after taking power in 2022, Petro kicked off his peace plan by declaring unilateral ceasefires with the major armed groups.

This, coupled with lifting capture orders on commanders of illegal armed groups, was a goodwill gesture from a president with previous form as an M-19 guerrilla and a kind of “hey guys, I get you, come to daddy” message.

Holding back the military was a major miscalculation. Armed groups, now freed from their main adversary, turned their guns on rival gangs in a bid to snatch more territory.

In Catatumbo this is nothing new. The coca and oil-rich territory, with multiple back roads into Venezuela to smuggle cocaine and stolen gasoline, has seen decades of internal squabbles between rival groups, many still present.

In fact, on the drive down to Tibú, a nerve-racking journey over rutted roads with thick jungle, abandoned houses, and empty army checkpoints, we see signs of several Colombian armed groups that have spray-tagged their presence like randy tomcats.

First up is the AGC, graffitied on a wall, the remnants of the AUC paramilitary forces that aligned with a state in past decades in Catatumbo, torturing and killing thousands and even burning their victims in purpose-built brick ovens.

Then there’s the EPL, also called Los Pelusos, formerly an Albania-inspired guerrilla army that morphed into a state death squad then dedicated itself to “100% cocaine trade” in Catatumbo.

Next up, on a stop sign, is the initials of the FARC-EP, dissident units from the large historic guerrilla army that mostly disbanded in a 2016 peace deal. These leftovers are known locally as FARC 33.

Last, not least, we see ELN, known locally as Elenos, sprayed in red on building walls, a Marxist guerrilla army stretching back six decades, in all corners of Colombia, and now also rooted in Venezuela as a mercenary army for the autocratic Maduro regime.

The Plan Unravels

That the FARC 33 and ELN would unleash merry hell in Catatumbo in the middle of a peace process seems to have caught everyone by surprise. But it shouldn’t have.

Already over two slow years Paz Total, had unravelled in other hotspots such as Putumayo, Cauca and Caqueta, and even brought recently pacified areas back into war.

Even worse, the pressure of on-off talks – and who had the right to represent who – forced some groups to further divide and declare war on each other, creating a dizzying array of new acronyms for conflict spotters.

For example the FARC EP EMC (Estado Mayor Central) spit out the renegade FARC EP ECBF (Estado Mayor Bloques y Frentes), which itself gave rise to the FARC 33, while the ELN spawned its own rebel rebellion with the CdS (Comuneros del Sur), which it has also sworn to eradicate. And there’s many more.

Such fratricide might at first glance seem like an opportunity. Why not let the armed groups eliminate each other?

The problem for Petro is that armed groups, even while dividing like amoebas, have also grown bigger and stronger.

This is partly down to the state’s hands-off approach to coca cropping. Bumper harvests led to record cocaine production even while global demand increased (Petro wrongly betted that fentanyl would replace cocaine in North American markets) and as everyone knows coke cash is the numero uno driver of conflict in Colombia.

Then global gold prices hit a record high, making illegal mines more attractive – and profitable – and fomenting new battles in new regions, even spilling over into Peru and Ecuador.

While unfettered armed groups scrapping over these riches, communities caught in the crossfire were crying out for more state protection.

Warring groups incessantly demand loyalty from civilians and leaders, and with wavering lines of control between combatants – families never know which gunslinger will next come knocking on the door – life in the campo became untenable.

Far from damping down slow-burn conflicts, Petro’s peace plan was pouring on gasoline.

Catching Fire

For a while at least it seemed that Catatumbo might escape this doomsday scenario and peace take hold. In fact, the region was voted the “most likely” (or maybe the only place) where Paz Total might succeed.

The ELN negotiations, while slow, were bearing fruit. And the FARC 33, a smaller outfit, more willing than most to lay down arms.

And for several years both guerrilla groups, now with a common goal to make peace, had coexisted with relative calm in this forgotten corner of Colombia, dividing territory and control of both rural and urban areas.

But then Catatumbo caught fire. Why?

The spark, according to the ELN’s own utterances, was “Petro’s nefarious paramilitary project”, a pact between the Colombian military and its new “allies”, the FARC 33, to kill ELN guerrillas in Catatumbo.

Worse, the Colombian state was re-arming demobilised former FARC fighters living in the region to rise up against their ELN overlords.

The ELN’s firm belief in this machiavellian plot explains their sudden and ferocious attacks on the FARC 33, demobilised combatants, their families and sympathisers, and their continued frantic hunting down of perceived enemies in towns like Tibú.

And to confirm their suspicions, the Colombian military seemed to be “rescuing” its FARC 33 “buddies” from the teeth of battle unleashed by the superior ELN, even flying them to safety.

The last bit was partly true; more than 100 of the FARC 33 fighters did surrender to the military as their only escape route from the ELN onslaught, and another 700 civilians whisked away in helicopters and land convoys.

Was Petro out to nobble the ELN? It seems unlikely he would torpedo his own peace plan.

Just Because You’re Paranoid…

Or did some maverick military commanders cook up their own deal with the FARC 33?

It’s possible. The Colombian army does have a murky past of siding with one guerrilla group – usually temporarily – to take out another. In fact the army coordinated with the FARC to take on the ELN in earby Arauca in 2005.

Or did the ELN – FARC 33 meltdown stem from some intricate intelligence operation that fed both sides’ paranoia with enough fake news to tip them into war?

Another theory was that Maduro created discord between the guerrilla groups as payback for Colombia’s failure to support his stolen election, inaugurated in January.

The autocrat in Caracas leads a regime that has long harboured Colombian guerrilla groups and is propped up by a military that cashes in on illicit proceeds from gold and cocaine.

Historically, ELN and FARC units sought refuge over the border. In recent years they’ve become guns-for-hire, first wrestling gold mines from the grip of criminal syndicates and setting up Venezuela’s cocaine industry.

I’ve seen this first hand.

Far From Home

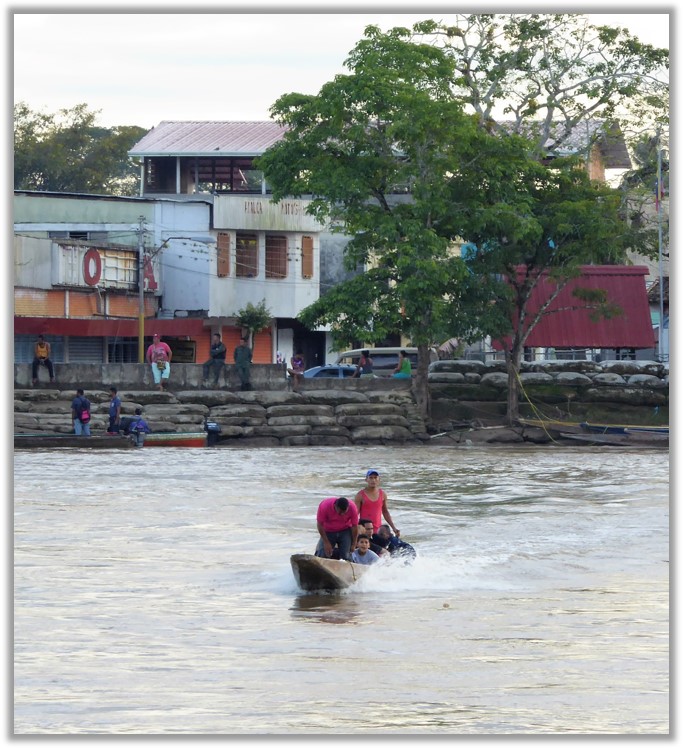

Some years back, in the far east of Venezuela, in Delta Amacuro at the mouth of the Orinoco, I bumped into a large group of heavily armed Colombian combatants sitting in a go-fast boat by the riverbank.

“You’re far from home,” I joked, on recognising the commander’s accent.

“Not as far as you,” he replied, figuring out I was not even from the continent.

He went on to explain his mission: “We’re here at the invitation of the Venezuelan president to clean up the towns.”

Their “cleaning” operations seemed to include hiring urban militias, setting up coca crops and controlling gold mines, while collaborating with the Venezuelan military.

Meanwhile back in Colombia, in the far west in the Chocó on the Pacific Coast, a friend recounted his accidental encounter with an ELN unit there that was “50% teenage Venezuelan fighters”.

That a niche Colombian guerrilla group has spread the entire width of northern South America should make everyone sit up and take note. It also complicates any ELN complicates any peace deal for Petro whose relationship is deteriorating with Maduro even as the Caracas regime is inserting itself as “guarantor”.

With Friends Like These…

Any mediation by Maduro is further strained by the fact that in January many hundreds of ELN fighters flooded into Catatumbo from Venezuela – clearly as a prelude to attacking the FARC 33 – many having cut across the country from their back bases in the Colombian department of Arauca.

That Maduro’s military gave the ELN “free passage” to Catatumbo has fueled a narrative that Venezuela is embarking on a Putin-style land grab. “ELN’s mobilization into Catatumbo has all the signs of an invasion with Maduro’s approval”, trumpeted one former president, failing to consider the ELN were always there anyway.

Petro is now requesting Venezuela to “control its frontiers”, somewhat ironic considering Venezuela has for years been demanding the same from Colombia. And awkward, considering Petro does not recognize Maduro as the legitimate Venezuelan leader following last year’s dodgy election results.

Not so the ELN, whose leaders for decades have claimed to support Venezuela’s revolución bolivariana and its goal of continental socialism.

In return Maduro has employed the ELN fighters to good effect, as brutal pacifiers in the Mining Belt, patrolling the borderlands, or suppressing other insurgent groups, or oppressing his own opposition, often in collaboration with the GNB, or Guardia Bolivariana Nacional.

Publicly Maduro denies any official connection with the ELN, well aware his reliance on foreign paramilitaries (as they are seen on his side of the border) has infuriated many Venezuelans.

Added to which, any thaw in relations between Maduro and the Trump administration could drive a wedge between Maduro and the Marxist-Leninist rebels.

But bringing their rubber boots to heel could prove as tricky for Caracas as Bogotá.

According to some estimates around 50% of the ELN’s combatants – around 3,000 troops – are based there, and these seasoned fighters tend to outgun, outwit and outperform the rather ramshackle GNB.

Maduro might wish he never invited them in.

When Two Tribes Go to War

Whatever machiavellian manoeuvres were behind Catatumbo’s current crisis, most agree that the January 15th murders of the funeral home family were the trigger for the ELN’s extermination campaign against the FARC 33.

But even then facts were twisted. Colombian media quickly blamed the ELN for the funeral home killings, but a month later two FARC 33 guerrillas were arrested for the attack.

The outcome in Catatumbo has been a routing of FARC 33, as our man in the plaza recounts with some glee: “One group got too big for their boots and the other one kicked them out.”

According to Paza Man, the FARC “left town with nothing, and now the ELN are taking everything. Trucks, cars, houses, hotels. It’s a bonanza”.

Many others tell me the “town has emptied out anyone related to the FARC 33”, even as displaced families have flooded in from the rural areas. In Tibú “one third of the town has fled,” suggests another contact.

But are they gone for good?

Another tidbit of information comes my way: the FARC 33 had been running a huge loan-sharking operation around Tibú, with many businesses and families owing “thousands of millions of pesos” to the armed group.

With this much at stake, could the FARC 33 fight their way back? With threat in mind, the ELN is gunning for total control. In Tibú that means “going house to house, street to street, clearing out anyone seen as a threat. If you stay, you die.”

All this right under the noses of the Colombian military.

Unsung Heroes

As usual in conflict Colombia, I’m struck by the resilience of the community leaders living in the middle of this mess. Anyone upsetting any armed group becomes a potential target. Community leaders are constantly in their sights.

In Catatumbo communities have no choice but to deal with “los que manda” – “those in charge” – historically the ELN or FARC. This puts leaders, teachers, priests and civic workers under intense pressure to walk a thin line between warring parties.

Any interactions come at high personal risk, such as intervening to stop child recruitment or stepping in to thwart a punishment squad.

You hear stories from all corners of Colombia: a community leader stands in front a young man stood up for execution. A community rallies to march on an “chop house” where a gang has taken a teenage girl for torture and dismemberment. After a clamour, the heavily-armed pandilleros lets her go.

In one case in Catatumbo, a guerrilla group is constantly stealing cars from an NGO bringing life-saving services to the rural areas. Several times cars are taken at gunpoint, leaving staff traumatised, and even abandoned in remote areas.

“A community leader went to the guerrilla camp and insisted the stealing stop,” I’m told. The commander concedes and the carjacking ends.

These stories, though, are rarely made public, or such interactions are misinterpreted by journalists – who hardly set foot in the zone – as complicity in the conflict. In reality social leaders are its unsung heroes.

In and around Tibú, communities have organised themselves to bring schooling, electricity, water supply and some level of calm to a traumatised population. And engaged successfully with NGOs to build schools, houses and community structures.

Schools are particularly vital for keeping kids out of the clutches of armed groups, and giving a future that doesn’t include growing coca. But the shadow of violence is persistent.

A teacher tells me that “keeping the school open is vital to breaking the cycles of violence.”

Orders to Capture

In Catatumbo that won’t happen any time soon. Petro has scrapped his peace plan with the ELN, and political pressure is building for the state military to engage the guerrilla group.

The state has reinstated capture orders for senior commanders. The hunters will become the hunted.

But when?

For now, in Tibú, there are rumours of informal “non-aggression agreement” between the army and ELN. This makes sense given the proximity of heavily-armed opponents largely separated by shoppers, families and kids on roller skates.

Life goes on, as do the targeted killings.

“You could say it’s a tense calm. An extremely tense calm,” reiterates Plaza Man.

Both sides will be plotting their next move.

Looking out over the rumpled hills of Catatumbo it strikes be that the Colombian military will have a herculean task to dislodge the ELN.

The terrain is a guerrilla’s dream with gullies, dense jungle and tree cover, and numerous easy escape and resupply routes to Venezuela. And in the veradas – the rural areas – the ELN are already sowing landmines on the trails and mule tracks better to protect their hideouts.

Totally Taking the Peace

And Petro’s Paz Total, while strengthening the guerrillas, has weakened and demotivated the military, particularly senior officers fuming that they weren’t originally consulted on his peace plan.

If they had been, they would have said clearly that opening negotiations with a cease-fire was a bad idea. Previous experience in Colombia shows that peace talks should be paralleled with increased military operations to keep the rebel groups under pressure. This was how Santos brought the FARC-EP to the table in 2016; his army engaged the guerrillas right to the wire.

Perhaps predicting the current outcome, many veteran officers and experienced soldiers have in recent years resigned, while others were forced out. Some now are mercenaries as far away as Sudan.

To add to this FUBAR; the Trump presidency has slashed US funds to Colombia, partly grounding a fleet of US-maintained Blackhawk helicopters, essential to army and police operations.

For the Colombian soldiers the job just got harder.

House of Thunder

With the implosion of Paz Total, Colombia is under a dark cloud. Already ELN and the AGC are intensifying combat in the Pacific Chocó region, with families displaced or confined.

And another flashpoint, the Sur de Bolivar region, is on alert for revenge attacks from FARC dissident groups which share territory with the ELN. In fact, the two guerrilla groups were previously buddied up to repel AGC incursions in the coca and gold mining zone.

Some pundits are calling it the “Catatumbo effect”, and Petro would be wise to reflect on the origin of the name itself.

“Catatumbo” means “House of Thunder” in the local Bari language, referring to a unique and extraordinary atmospheric event; a constant electrical torment.

This anomaly is caused by the confluence of the Rio Catatumbo which flows out of the cool Colombian hills into Venezuela’s humid Lake Maracaibo creating an enduring electrical torment that has sent lightning bolts to split the heavens since human records began.

This spectacle was raging when first Spanish navigators, in the 1500s, used its loom as a natural lighthouse to mark their nightward passage along the South American coast.

As for me, I marvelled at the Faro del Catatumbo many years ago, when camped in a remote Bari village. All night I could see the night sky pulsate while thunder rolled over the dark trees.

The situation back then was equally complicated, with towns crammed with families displaced by fear while in remote villages guerrillas in green uniforms rested in the shade of broad trees, then casually shouldered their guns to stroll through coca plantations into Venezuela. Then the unmistakable shudder of heavy helicopter blades as airborne troops skimmed the horizon.

Catatumbo is Colombia’s never-ending storm.