Colombia’s Tuluní cave

Swimming a tropical river into Colombia’s Tuluní Caves.

Posted July 2019

See similar posts:

– Gorgeous Guaviare

– The Amazing Amazon

– Isla Fuerte: Unkown Island Paradise

The best way to arrive at the Tuluní Caves is floating down the Rio Tuluní, a clean, green river that carves its way through the limestone foothills of the Andes central range and into the dark maw of the cavern itself.

The river has worn the soft rock back to its loose state, the outcome being a delightful gorge with chest-deep water and comfortable sand underfoot. The perfect place to lie back in your lifejacket and go with the flow.

‘Best to get out here and walk a bit,’ advises Fernando our guide, interrupting my reverie of mazy meandering. We flap our hands to steer ourselves to the rocky shore and send lorikeets darting through the dappled greenery that tops the limestone walls.

Sure enough, just downstream is a small waterfall strewn with smooth logs from last season’s floods which we by-pass by scrambling along the side of the river. Looking up at the sheer side of the deepening gorge, I realise there’s no way up. The only exit is downriver, towards the caves.

Once a Zona Roja

Not that there’s that much to worry about. Fernando knows the area well. Originally from Planadas, a poor rural town a few hours south, he is one of a group of campesinos displaced by conflict that found a rural haven here. Tuluní itself is a vereda, rural settlement, thirty minutes by car from Chaparral, another Tolima town once considered zona roja in a region pulling itself out of a violent past.

At first this conflict shadow seems at odds with the physical beauty of the region: a startling panorama of mountains, rocky outcrops and buttes, draped in tropical vegetation alive with chattering birds. But it’s that never-ending parade of ridges and chasms that creates an impossible geography for farmers whose bahareque houses cling improbably to green mountain flanks.

The farms we pass seem scrappy and poor, with busted machinery and broken fences. Horses at the roadside are scrawny with chafing wounds from overwork by their hard-eyed owners. ‘Hard on their animals, hard on themselves’, I mutter to myself as we drive by.

I am hardly surprised to later learn that in the 1960s this very region was the cradle of the FARC that grew out of that ‘peasant leagues’ that defended small farmers from government-backed evictions as their land was taken by rich landowners. The folded landscape provided a natural redoubt for the guerrilla army that formed after 16,000 Colombian troops attacked Marquetalia, a Tolima village of one thousand inhabitants.

Perhaps the stigma of that painful history – and what happened next with five decades of civil war – that explains why there doesn’t seem to be hordes of tourists charging into Chaparral and its idyllic surroundings. It’s the school holidays, I’m travelling with the kids, and we haven’t seen another tourist, not in the otherwise bustling town of Chaparral, nor anywhere near Tuluní. In fact, we turned up at the village on spec and were lucky to bump into Fernando on his way to work.

Better than pulling weeds in a rice paddy

He clearly prefers guiding tourists to pulling weeds in the local rice paddy. ‘It’s only a 45-minute walk to the caves,’ he tells us at the start, so I mentally calculate one and a half hours, which turns out to be correct. We park the car at a nearby farm and head off carrying lifejackets. We quickly reach the Rio Tuluní, but wade it to keep walking and cut across farmland to shorten its winding loops, eventually crossing it twice more before the drop-in point.

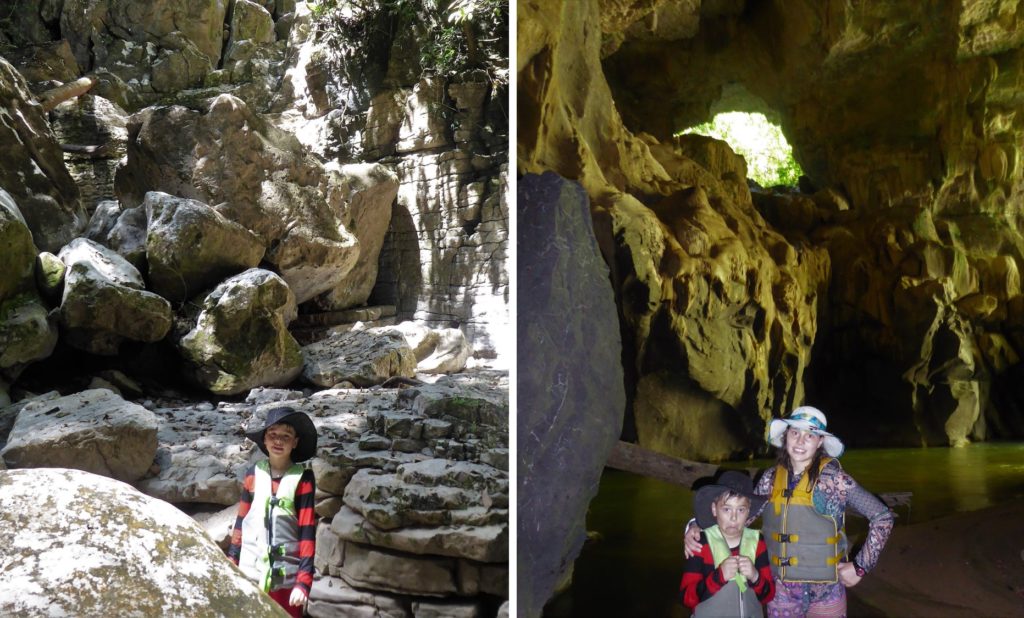

The kids are loving it. This is the kind of river they can enjoy: warm, not too deep, clear enough to see the bottom, and surrounded by stunning scenery that Colombia provides in abundance. But as the gorge narrows, and the river quickens, I feel a tug of worry at obstacles ahead. We’re now having to wade some quite ferocious torrents, sometimes carrying little Sam – eight years old – on our backs. So far, he seems happy.

The problem with off-the-beaten track adventures in Colombia, I remind myself, is that ‘health and safety’ is an unexplored concept and you are never quite sure what comes next. But then we’re at the first cave, a high limestone crack running untold kilometres into the mountain and home to flocks of guacharos, or oilbirds, nocturnal fruiteaters that roost in caves.

Oops, no torch!

In our rush to leave we only brought one torch. That counts out any deep cave exploration. The kids don’t mind, since Fernando has already told them about a group of local explorers who went ‘deep into the cave a few years back and never came back’. Another good reason not to go deep. So we push on downriver.

The second cave, La Catredal, is even more spectacular, with the mountain swallowing the river whole. I hope there might be a hidden trail into the cave, but no, the only way in is by river. With Fernando in front we drop in off an overhanging rock and, with one kid clinging to my back, wade through the swirling water towards the darkness.

As my eyes adjust to the gloom, I realise the cavern is actually a giant tunnel, with a roof as vaulted as any cathedral, with fluted limestone columns and stalagmites worn smooth by the river. High above, two massive natural skylights draped in mountain greenery bathe the cavern in a liquid green light.

We wade out to a narrow beach to enjoy the spectacle. Further downstream the cavern opens out to a huge natural arch which frames a gloriously wooded riverbank. But our way out is, surprisingly, back into the cave and up over a boulder slope to a hidden upper gallery. After a tricky scramble up the slope, we stop to admire some stalagmites, on known as the ‘Copa Mundial’, and sure enough it does resemble the Jules Rimet trophy.

Then we climb a steep narrow trail up the canyon side, Fernando swinging his machete to clear the undergrowth – it’s clear that not many visitors have passed this way recently – and we are back on a softer hill, covered in small chaparro trees, of which the large abrasive leaves ‘make natural pot-cleaners for local housewives’, and gave the town of Chaparral its name.

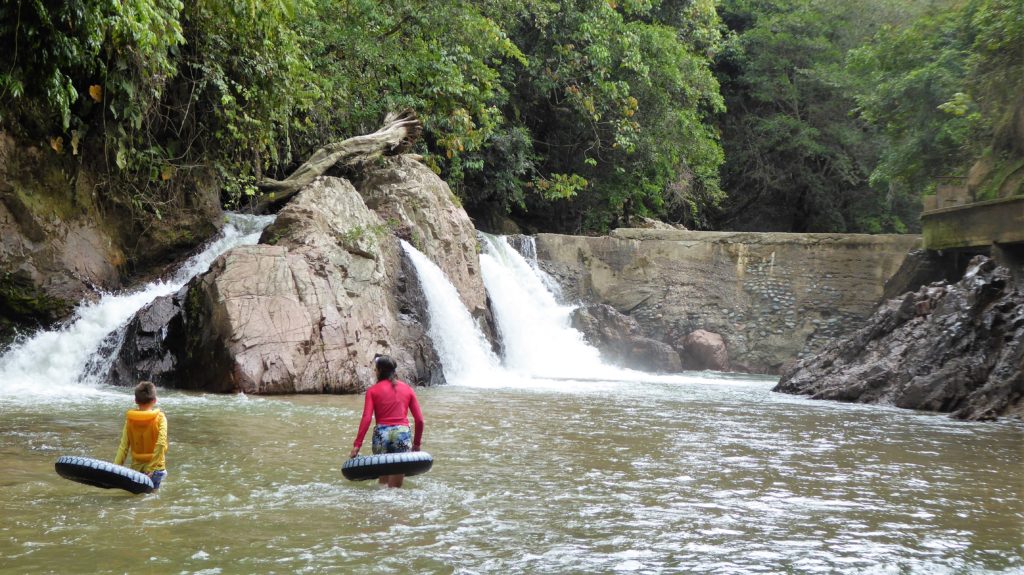

It’s a hard, hot, walk back over the fields, then a short drive to the Tuluní village, where we lunch at a small local restaurant. But before we leave there’s one more chance to enjoy the river, which flows here too. A small agricultural dam has formed a balneario (swimming hole) where we can float some more and forget the big city we will – all too soon – get back too.

PRACTICAL STUFF

How to visit: Tuluní Cavesare best visited as part of a trip to Chaparral, Tolima. You will need pre-book a local guide. If travelling from Bogotá, the visit could be done on a weekend. The trip we did above was done in June 2019, in dry weather. Conditions and route could vary in the rainy seasons (usually March – May, October – November). The tour last at least half a day, depending on how long you take to walk.

How to get there: first head to Chaparral, Tolima, which 250 kilometres, six hours drive on good roads from Bogotá. There are regular buses and micros with Cointrasur from the south or Salitre bus stations in Bogotá. From Chaparral you can get a campero or ‘Uaz’ (pronounced ‘huaz’) rural jeep to Tuluní, which is 11kms or 20 minutes south of the town. You can find the camperos at the local market, two blocks south of the plaza, just climb on the next one leaving. Ask to be dropped at the ‘Tuluní Balneario’ sign. Here walk down the track to the bridge, then take a left turn towards the Balneario El Tambor where you will also find some restaurants, rural hotels and Tuluní Vive organisation that orgsanises the cave tours.

If driving, the Tuluní road leaves Chaparral on the southeast of the town, best to ask directions. The first 500 metres are dirt road, then it’s good asphalt road all the way. After 11 kms you’ll see the Tuluní Balnerio sign, take the dirt track to the right, over the bridge, to find the balneario. You can park there while you do the cave trip.

How to book: Tuluní Vive has a Facebook page and email, tulunivive@gmail.com, or you can call the guides on 313 323 5849 (Fernando) or 311 520 7649 (Diego). The guide charges costs $120.000 total for groups up to 10 people. Life jackets and hard hats are included.

What to bring: light clothing that dries easily, tennis shoes you can walk in and swim in, a wet-bag for your camera or phone, good sun hat, sun cream, insect repellent, snacks, drinks.

Some links:

Sin Brujula video of visit, with driving route:

Tuluni Vive Facebook page

See Colombia page

Colombia de Fiesta