Do you have an altitude problem?

Steve Hide

A version of this post was published in The City Paper in 2016

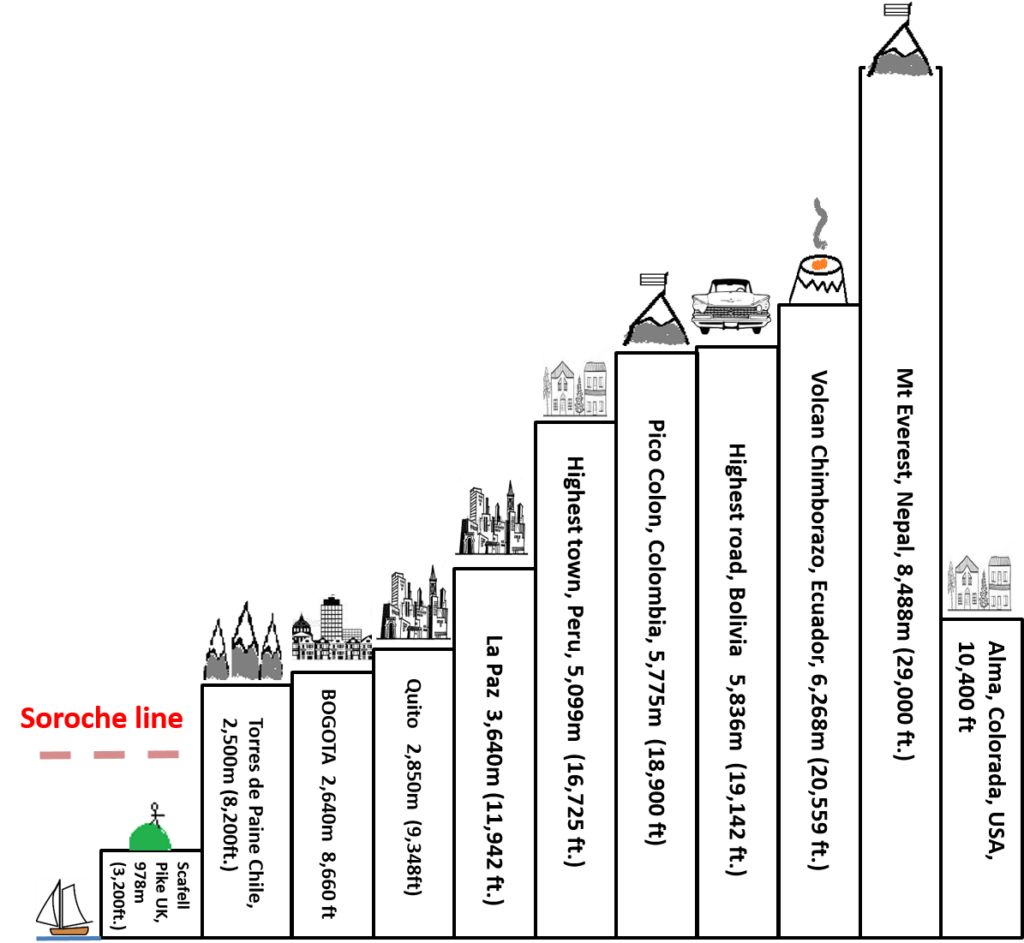

Bogota’s altitude can catch you unawares when you first arrive in the city. The effects are quite mild, not like in La Paz where recently de-planed tourists lurch around the witch market like zombies, or Cusco where your day at the ruins can end in ruin curled up in bed with a thumping headache. No, in Bogota mal de montaña or soroche (as it is called in many parts of the Andes) or is more subtle and hardly mentioned at all, so it is surprising to realise that the Colombia is the country with the 4th highest capital (after Bolivia, Ecuador and Bhutan) at 2,640 metres (8,660 feet).

Altitude, of course, affects a lot more than just our capacity to climb stairs, it also has a profound effect on the environment particularly in the tropics where driving up a mountain for a day can bring dramatic changes of climate and vegetation from cactus-filled dry gullies to moisture-dripping rainforest to temperate pine forests to chilly Andean moorland and even snow. It would take weeks to drive the same dramatic changes in ecosystems on a road at sea level (and probably require covering Belize, Mexico and half the USA).

How bad is it? First let us differentiate between altitude sickness, which is an unpleasant but bearable inconvenience to travellers arriving to places like Bogota, and more serious health risks such as pulmonary oedema which in its severest form fills your lungs with pink froth and kicks in at around 4,000 metres (13,000 feet) and cerebral oedema, a kind of brain failure, which is often fatal but very rare and usually strikes mountaineer at extreme heights in the notorious ´death zones´ of the 8,000 metre peaks in the Himalayas.

No jogging the first week…

So how does it all work? A casual glance of the streets of Bogota does not give much away. There are no Beware of the Altitude signs on the pavements and upmarket hotels do not routinely offer their guests blasts of bottles oxygen like in Bolivia and Peru. But the fact you are standing on a street corner wearing a warm jacket while on the same latitude as the Amazon jungle should give you a clue. Air pressure drops exponentially as you climb from sea level, and temperature drops on average 1 degree every 150 metres up. The air is thinner so there are fewer molecules to bounce around and keep warm and not as much oxygen gas to breathe in and recharge your red blood cells.

To have any risk of these more severe forms of mountain sickness in Colombia you would have to scale the highest peaks such as Pico Colon (5,775 m or 19,000 feet) or be on some high-altitude trek such as the Cocuy Circuit, which starts at 3500 metres and ascends to over 5,000 metres, areas only accessible to serious hikers and mountaineers. It is worth noting, though, that in other parts of the Andes there are main roads in Peru where buses pass at 4,800 metres and jeep roads in the Bolivian Altiplano over 5,000 metres high.

Click here for my post Dying for a Breath of Fresh Air on pollution in Bogotá

Back in Bogota, you are at the lowest end of the altitude scale in terms of physiological effects and some travellers arriving in the city will not notice it at all. Altitude sickness is quite a fickle condition and at time paradoxical, for example it seems to affect more people with a high level of physical fitness. I figured this out dragging tourists over Andean trails as a tour guide. Most groups could be roughly divided into exercise fanatics ready to test themselves against the mountain, and the drinkers and smokers who reckoned on restricting any physical activity to strolling from their hotel room to the bar.

In the end it was the smokers and drinkers who won out, perhaps as a result of taking things slowly and the years spent inadvertently preparing their bodies for a low-oxygen environment. Altitude, what altitude? Meanwhile the fit types would nip out for a quick jog then end up on a glucose drip in the local hospital.

The first rule of altitude, then, is do not try and fight it. The human body coming from the lowlands needs several days to properly acclimatise to the lack of oxygen above 2,500 meters, and there is no real easy way to short-circuit the process. The first and most obvious response is heavy breathing and a faster heartbeat which causes changes to the blood and other biological changes such as sweating and palpitations, a slow-down of non-essential bodily functions such as digestion, and an increased need to pee. Something like your first date, then.

The outcome, unfortunately, is a more like a hangover. Dehydration caused by faster breathing in the dryer air causes with headaches and nausea can set in digestion slows down. These symptoms are usually mild but can become very quickly exaggerated by any strenuous activity, leading to a migraine-like headache and vomiting in severe cases. So take it easy the first few days after arriving in the city. Take taxis, don’t walk. Avoid any aerobic exercise or the itch to walk up Monserrate, which peaks at 3,150 metres (10,300 feet). Take frequent rests and maybe even a siesta (hey, you´re still in Latin America even if it feels cold).

There are some medical drugs you can take which alleviate the effects such as Diomox, but they have side effects such as fatigue so much better to allow time for the natural adjustment to take place, which usually takes four days and is the time it needs for your body´s metabolism to reset to the thinner air.

Coke adds life

A better cure is sweet herbal infusions or aromatica as it is called locally. Some people swear by coca tea, but actually any warm sugary fluid will pick you up as it is the glucose which alleviates the symptoms. I also found Coca Cola, long recognised as the best hangover cure (as students we called it The Black Doctor) but also an almost miraculous cure for altitude with its rich mix of caffeine and sugar. This was something I picked up driving trucks on Peru, sometime climbing from sea level tom 4,500 meters in a day and working hard at the wheel to keep on the hairpin roads. The Peruvian truckers, I noticed, would only tackle the high passes with several bottles of Coke on the cab. I imagine Pepsi works just as well.

Once you have got over the four-day hump your altitude problem will mostly be behind you. Be warned though, if you go higher by another 500 metres your body will need to reset to the new height (though having been used to a higher zone will be easier), and the exponential effect of altitude means that at heights above 4,000 metres your body will still feel new effects at lower increments.

Live High, Live Long

If you stay and live around Bogota, though, any altitude sickness will soon become a distant memory. For a month your body will increase your red blood cells, peaking after a month. You will probably start to feel healthier and more energised, with a good appetite but eating less, a maybe needing less sleep.

The long term effects of living high are not fully understood by scientists, but there is a strong consensus that at the altitude of Bogota the human body thrives. Medical studies have shown a range of benefits from improved cardio-vascular health, a lower risk of heart attack, less childhood asthma and a 40% lower chance of becoming obese. These benefits are related to increased body metabolism and the extra vitamin D produced by the high UV sunlight.

From my own unscientific studies I can report that for some reason food tastes better at altitude, something I have noticed over many years criss-crossing the Andes. So there you have it folks: come live in Bogota for fine dining with less chance of getting fat. Just be aware that the lower air pressure reduces the boiling point of water to 90 degrees centigrade, so don`t expect a good cup of tea.

The golden rules of altitude

Respect the acclimatisation period and take it easy!

This means for the first few days arriving above 2000 metres:

- no strenuous exercise for 4 days at least. Stroll, don´t run.

- take naps and eat light, your tummy will thank you.

- drink lots of sugary drinks to keep glucose levels up.

- avoid alcohol, no point adding a hangover to a headache.

- avoid medical drugs (Diamox etc). Safer to naturally acclimatise.

- if you feel really unwell, go down!

For people planning high altitude trekking (ie Inca Trail or Cocuy Circuit)

- ensure your itinerary includes a week’s nonstrenuous time at high altitude (preferably close to 3,000 metres) before hiking

- check carefully your route to ensure slow ascent, overnight stops at lower altitude (in valleys, preferably under 4,000 metres).

- be aware of signs of altitude sickness and go down if you are unwell.

Altitude sickness and high flying

If you are feeling strung out after a long-haul flight, one reason is down to altitude sickness. Most commercial airliners are designed to cruise with a cabin pressure of 2,400 metres (8,000 feet), roughly the altitude of Bogotá. Over a long flight, this high altitude plus factors such as the time zone difference, sitting in a chair for 12 hours, airline food, dry air and overdoing it with the free drinks trolley combine to make you feel jet lagged at the end of the flight.

Evidence for the role of altitude in jet lag comes from extensive tests done by Boeing when designing the 787 Dreamliner. They subjected 500 volunteers for 20 hours stints in a mock plane cabin at different altitudes. At a pressure equivalent of 2,400 metres (8,000 feet) – the usual airline cabin pressure – a significant number of test subjects showed signs of mild altitude sickness with headaches, muscle aches, fatigue and nausea. At the 1,800 metres (6,000 feet) these symptoms all but disappeared.

Boeing then designed the 787 with the lower cabin pressure equivalent of 1,800 metres altitude, which has been touted as a major selling point for the plane. Personally, I have flown transatlantic flights several times with the 787 (with Aeromexico) and found the improvement quite remarkable, arriving much more refreshed.

So probably altitude does play a part in long term flight health, and Boeing´s tests suggest that Bogotá is high enough to effect most people with some form of altitude sickness.