Dying for a breath of Bogotá air

by Steve Hide

This article first appeared in The City Paper in 2017

I give up smoking and take up the supposedly healthy activity of cycling, only to find myself puffing up a Bogotá hill while gulping down the thick warm fumes from an old bus. Then I read somewhere that mega-city citizens of Latin America inhale enough smoke particles to equal two ciggies per day. So much for cutting down.

But the more I read, the more I realise that air pollution is a tricky subject, not only because much of it is invisible (though Bogotá’s buses chimeneas – chimney-stack buses – are a handy visual reminder) but because, worldwide, the contamination goal-posts seem to change.

Take diesel cars for example, touted as clean and green until the recent scandal of emissions fraud. Companies like VW found the easiest way to meet standards in the US and Europe was to design cars with built-in gizmos to cheat the tests.

These type of scandals didn’t resonate much in Colombia, though, perhaps because nearly all cars are petrol, but also because the owners of larger diesel vehicles – mostly trucks and buses – have a more straightforward way to cheat the pollution tests: threats and bribery.

Also read my post on Bogotá’s altitude, Do You Have an Altitude Problem?

Which is why if you find yourself out on Bogotá’s streets on a regular basis, you will also adopt the local habit of pulling parts of clothing over your face as a smoky truck chugs by. Can a thin layer of cloth somehow protect you from this rich mix of carbon monoxide, nitrogen dioxide, sulphur dioxide, ozone and microscopic soot particles? Somehow I doubt it.

Official statistics are hardly reassuring. Bogotá is Colombia’s second most air-polluted city, after Medellin, and the tenth worst in Latin America (Lima in Peru and Cochabamba in Bolivia are the worst).

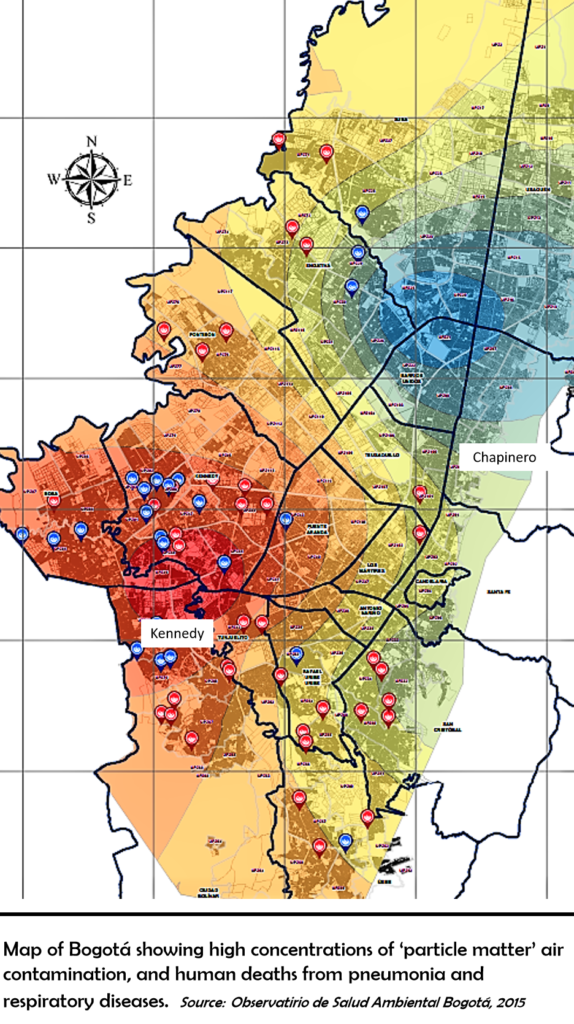

Of course, vehicles are not the only air polluters, and factories and mining can account for a third of a city’s contamination. But given that large trucks and buses also tend to concentrate in industrial areas, it is hardly surprising that Bogotá´s smog hotspots are around Kennedy and Ciudad Bolivar in the southwest of the city, which also, no surprise, are also the poorest ‘lower strata’ parts with less green spaces and more streets clogged with older cars.

SMALL LUMPS OF SMOG

How bad is it? Fairly bad. There are many measures for air pollutants, but one of the most telling is ‘PM2.5’, or small lumps of smog 2.5 micro-meters or smaller (think: 30 times finer than a human hair). These cause the haze you can see over a city, and asthma, heart-attacks, lung disease in your body. They even swim around in your blood stream. Most come from vehicles.

Parts of southwest Bogotá record an annual average of 30 micro-grams of PM2.5 particles per square meter of air, three times levels recommended by the World Health Organisation. This sounds bad enough, but in peak hours – when most vehicles and humans are on the street – the levels can peak at over 80.

This is creating an ‘environmental disaster’ says Dr Gonzalo Diaz, a Bogotá medic who has dedicated more than 20 years to monitoring health impact of poor air in the city, and regularly pops up on chat shows and radio slots, as well as publishing his views and data on his contaminacionenbogota blog.

He quotes WHO figures that annually man-made air pollution kills 12 million worldwide and, he claims, increases mortality in Bogotá by 14%. Around 600,000 children under the age of five are treated for respiratory problems every year and these illnesses are the number one cause of infant deaths in the capital.

SMOKY VOLVOS

‘Everyone in Bogotá breathes air that is contaminated, poisonous and carcinogenic, no matter where they live,’ he says, aiming much of his ire at the city’s network of diesel buses, the ‘Smoky Volvos’ of the mass-transit systems, and the corrupt system of vehicle emission tests.

But he goes even further and accuses the city authorities of falsifying the air quality data: on the smoggiest days when social media is all a-twitter over the bad air, he says, the real-time data streams of AQIs (air quality indices) suddenly freeze then re-appear later as ‘normal’.

These claims put Dr Diaz at odds with the official reports that Bogotá air quality is – over decades –slowly improving. But that may be hard to prove as ways of measuring, and what types of contaminant to measure, also change over time.

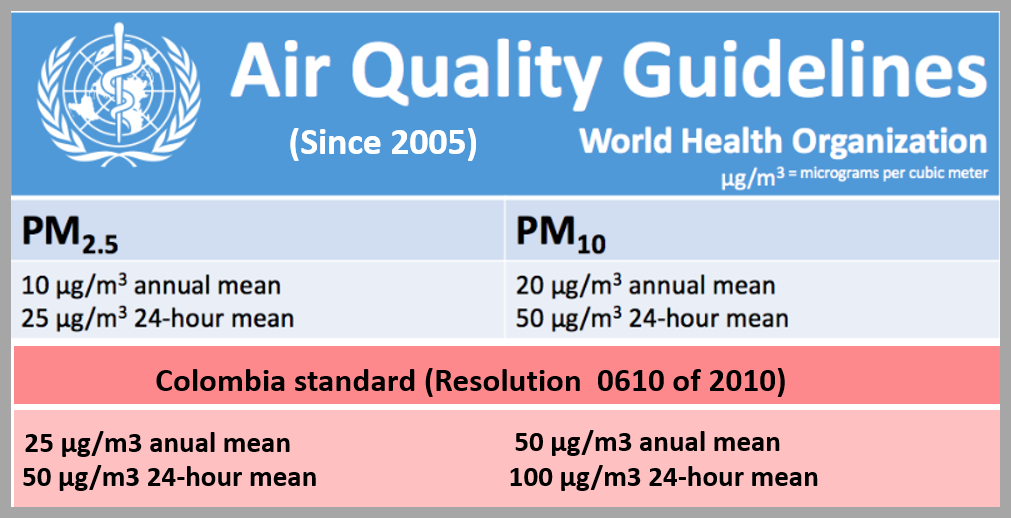

Where he is clearly correct though is that currently Colombia has adopted much lower standards for clean air than recommended by the WHO. In Bogotá a ‘good’ annual air average is 25 micro-gm/m3 of PM2.5 particles, more than twice as dirty as the maximum 10 micro-gm/m3 considered safe by the WHO.

This sleight of hand allows city politicians to claim the air is OK when by international standards, it’s not. It also helps then wriggle out of inconvenient questions from the newspapers. After all, air quality data is perhaps only second to crime stats as a proxy measure of a politico’s popularity.

So who measures the air? In Bogota the office of the District Environment Secretary operates a 13 air testing stations in a network called RMCAB (Red de Monitoreo de Calidad del Aire de Bogotá). Data is fed in real-time to an interactive map you can find at ambientebogota.gov.co and forms the basis of three-monthly and annual reports.

These feeds also record climate data bearing in mind that levels of air pollution also depend on factors such as wind, rain and temperature. In this sense Bogotá is somewhat blessed sitting on an open plain with almost constant wind flow to disperse the air, particularly compared to Medellin where the enclosing hills create Colombia’s worst fug and occasional health emergencies.

One downside of the capital – from the pollution perspective – is its high altitude at 2,400 metres which makes fuel combustion less efficient. But can this account for all the chimney-stack buses and trucks? No, this is mostly down to poor maintenance and lack of exhaust filters.

Research shows that in any given city 25% of the vehicles cause 90% of the pollution. Most if these will be old diesel trucks and buses, each of which can pump out 150 times more deadly fumes than a gasoline car. According to the Secretaría de Ambiente’s own figures, 43% of Bogotá air pollution comes from trucks, 23% from buses (including SITP and TM buses) and 14% from other diesels (gasoline cars make up the other 20% of the mix).

You see diesel engines work to fine tolerances and wear over time. Metal parts like piston rings and valves need periodic replacing or regrinding. Basically, any engine that blows black smoke needs downtime in the workshop. Then, at the rear end, the exhaust gases can be made healthier by catalytic filters which catch the soot and some gases. Eventually, after some hundreds of thousands of kilometres, the wear is irreparable and the vehicle ready for scrap. This all costs time and money. So for many bus fleet operators in Bogotá: why bother?

The irony then is that our mass transit system, theoretically there to make the city cleaner and more efficient, is slowly killing us. And as usual the city authorities have a ‘plan’ somewhere in the pipeline to deal with it, but not much action.

For the SITP and colectivo buses, for example there is a ‘mobile exhaust emission testing team’ (though in six years I have never seen one) and a ‘smoky bus’ hotline at the council where the public can phone in, denounce a smoky bus, and the authorities will ‘follow the vehicle and test its emissions’, clarifies a secretaria spokesman a few years back. But few chimney-stack buses are ever caught because ‘citizens don’t know how to denounce these vehicles’, he goes on. So blame yourself for not phoning in.

As for the Transmilenio buses – which you might imagine are under tighter control – the scenario is just as bleak. Various city mayors regularly battle with the fleet owners (the TM is a private ‘public’ system) to replace old stock and limit the buses’ mileage, but the owners fight back and continue to squeeze as much profit from the rickety system as they can. This year the city caved in again and allowed buses to keep rolling on to 1,500,000 kilometres. That is to the moon. And back. Twice.

Then there is the plan to fit exhaust filters to old buses and trucks, which could in theory reduce their pollution by 90%. This obvious and simple solution is in the law statutes but currently suspended by the mayor for fear that the filter costs will ‘raise the transport tariffs’.

There are some silver linings: in recent years Colombia’s congress has forced fuel suppliers to massively reduce sulphur content in diesel fuel, a plus for the environment. And despite its still-critical levels of air pollution – with 3,000 related deaths last year – Medellin is managing reductions with its electric Metros, cable-cars and a plan for electric taxis.

But perhaps for inspiration Bogota needs to look at neighbouring capital Quito. While still far from the perfect, the Ecuadorian capital, geographically socially similar to Bogota, has now joined the top-ten clean-air cities in Latin Americas. One reason for that is a more uncompromising approach to smoky buses. Living there some years back I remember police stopping public buses for on-spot emission testing, then towing the bus away under armed guard when it failed.

Of course as passengers on the bus we were not so happy to be stranded by the roadside but, looking back, maybe it was the right approach. Couldn’t Bogotá try the same?