Guavio dam lake

This wild and scenic corner of Cundinamarca is surprisingly close to Bogotá. It makes a great weekend road trip from the capital. (Or you can go by bus).

A version of this post appeared in The City Paper in 2015

See related posts:

– La Chorrera: Colombia’s highest waterfall

– Villa de Leyva

– Backroads of Santander

– Boyacá: backroads to El Cocuy

– Guatavita: a legend lives on

The closest rural area to Bogotá is the department of Cundinamarca which rings the mega-city like a green donut and has an amazing variety of terrain from high peaks, paramo moorland, rolling farmland and jungle down to the steamy Magdalena River to the west and the Llanos plains to the east, all interconnected by relatively good roads and public transport. I say relatively because any journey anywhere in the Andes is prone to the delays and unexpected, from landslides to cycling races, to village fairs that for some inexplicable reason take place on the main through-fare (and might actually be fun if you are not in a hurry).

Of course weather plays a big part of enjoying this generally rainy part of the world and the most dramatic Andean scenery soon looks likes a wet weekend in Wales once the mist comes down. Connected to this is the ancient Andean Curse of the Sun Cream, whereby shortly after applying Factor 50 to your kids’ faces, it starts to rain. This leads to intense family discussions about what is the actually the right moment to apply sun cream, or whether just hats might appease the Weather Gods. As a back-up plan it is always good to head to somewhere with some thermal springs, of which there a many throughout the area, so even if it does rain you can sit as smug as a snow monkey in hot volcanic water.

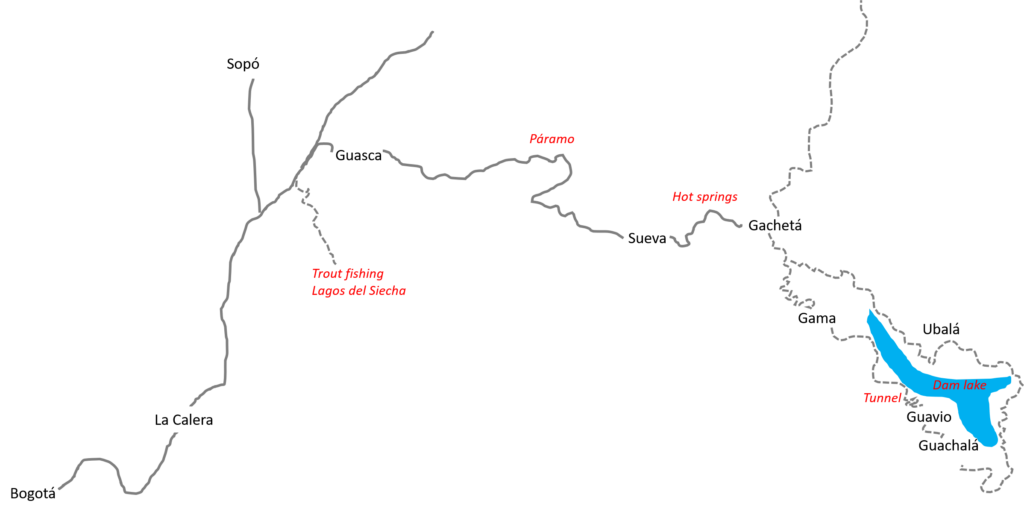

On our latest excursion to Guavio Reservoir, we got hot springs and by sunny weather, and spectacular scenery. The reservoir, known locally as the Embalse Guavio, is the lake formed by a hydro dam built in 1989 and sits in some spectacular canyons on the eastern slopes of the Andes about 130kms from Bogota over mostly back-roads. As usual, internet information on the area was a bit sketchy and how long it might take to get there, and actually what we might find at the other end a bit vague. But we set off anyway with a large scale map and a tank full of petrol and the kids chanting from the back seat – even before we left Bogota – ´how long before we get there?´ The answer to this was of course to crank up some 1970s rock music on the car stereo.

We exit the city along the fastest escape up and out through La Calera to the town of Guasca, which announces itself as ´Paradise on Earth´, an elevated claim but one which on a sunny day you might buy into: ascending to the long broad green valley framed by high rock-combed ridges is something of a spiritual experience after Bogota traffic. I find myself doing some mental maths on the cost-benefits of owning a small finca up there, until the voice of common sense says ´come back on a rainy day´. By that time though we are winding our way upward again into paramo moorland and some crazy rock strata. It is time for a geology lesson with my daughter.

´OK, these limestone rocks were once an ancient seabed. How did they get up here?,’ I ask her.

´I don´t know Papi. Was there a big explosion?´

I explain about continental drift and plate tectonics, but it is a bit hard while driving the car over the mountain road. Big plates, I keep telling her. Not plates like we have dinner on. Very big plates. Sometime later we stop at some road works and the workers are using large steel plates to form the drainage channels.

´Look Papi, plates,´says my daughter. ´Are those the same ones that they use the make the mountains?´

Even if I can´t properly explain how the scenery got there, at least I can enjoy it. And there is plenty to enjoy. Dropping down to the towns of Sueva and Gacheta has brought us to the over the range and the highest peaks are now behind us. It is thrilling to think the water that forms the clear mountain streams will flow thousands of kilometres through the muddy Llanos to the ancient sands of the Orinoco, across all of Venezuela and out into the Atlantic Ocean.

The valley here closes into the gorge of the Rio Sueva, and the some farmhouses nestle below some massive rock overhangs like accidents waiting to happen. After Gacheta we turn south towards the village of Gama. It looks close on the map but the dirt road makes a seemingly endless series of twists and turns over the steep hills. But by Gama there is still no view of the Guavio Reservoir so we head on towards Gachala, a town further on. The kids have long since stopped asking ´when will we get there´ (having twigged that so there is not really a ´there´) and are now focused on their stomachs: ´we want lunch´ they chant. I offer a cracker from the emergency food bag. ´No, we want real food,´ says my daughter, refusing the cracker just to make her point. There is a sullen silence from the back seat and I start to feel bad, like the mad dad from The Mosquito Coast, dragging my family to some dam lake.

Then we see the lake, a turquoise ribbon of water snaking through the gorge. More surprisingly is a large cement bridge that spans the gorge then abruptly ends in a sheer wooded cliff-side. Only when we get down there – all thought of food momentarily forgotten – do we realise that the bridge leads straight into a dark tunnel. This is both exciting and scary, as it also appears endless and the lights aren´t working. The tunnel is curved and the walls and ceiling are damp and dripping and carved out to give a scalloped effect. All in all like the inside of an intestine. I can´t help feeling we are giving Mother Earth an endoscope.

In the middle of the tunnel, which turns out to be over a kilometre long, I stop the car and turn out the headlights so we can experience pitch dark. After the initial shock comes howls from the back seat, and food is suddenly back on the agenda: we head off at full speed to Gachala, the largest town on the lake and our final destination.

We have chicken and chips in Gachala, and watch the speed boats that carry villagers across the lake to the villages and farms cut off by the dam water. The town is picturesque but very quiet. We head back the way we came, through the tunnel and over the bridge to Gama, and stop for an ice-cream in the plaza. It is also as empty as a graveyard. I ask the woman at the ice-cream shop where everyone is.

´It is like this most days except Sunday when absolutely everyone comes here from the villages,?´ she says.

´To have some beers?´ I suggest hopefully. ´No, for the Sunday mass,´ she replies tartly, though I would bet her best banana split that the farmers sink more than a few beers before wending their way back to their veredas on a Sunday night.

We backtrack to Gachetá then up the steep valley towards Sueva. A few minutes drive along the valley are thermal pools and small hotels and cabins, we stay at one – the Campo Alegre – with a thermal pool right by the boulder-strewn Rio Gachetá. The owner seems quite surprised to see us. ´How did you know there was a hotel here?´ he asks as he sweeps the dust and leaves out of the small apartment rooms we are renting for the night. ´We saw your hotel sign as we drove past,´ I explain. The hotel is ramshackle but the hot pool is delicious, fed by near-to-boiling water piped from a natural spring on the opposite hillside. There is no food on, and no restaurants nearby, so we make do with tamales from a nearby cantina. The kids are too tired to complain.

Next morning we are back in the hot pool, steaming in the morning chill, then back over the Páramo to Guasca where we stop to fish for trout at a ´sport fishing´ Lagos del Siecha fishing farm . I use the term lightly since the hungry fish seem to jump onto the hook and the skill seems to be how not to catch anything bearing in mind you are charged by weight of fish caught (and no returns, to the water that is). After 30 minutes fishing we have hauled out six large trout, our budget gone and our freezer space full.

Practical stuff

Bogotá to Gachalá is 130 kms so around 5 hours drive, with OK roads, though very windy and hilly. You could visit the dam lake in a day trip, though that would be rushed: best to overnight at the hot springs close to Gachetá or in a small rural hospedaje in the towns. You can get a bus to Gachalá from Bogotá with Valle de Tenza, with seven buses a day leaving from Bogotá’s

Terminal Central Salitre or (if you’re in the north of the city) from the corner of Calle 72 – 13.