Homicides in Colombia: 2024 update

My round-up of homicide data and trends for Colombia, based on recent official data (2023) and news reports and analysis.

I’ll be posting a parallel blog Is Bogotá Safe? 2024 and you can also see my2023 post on safety and security trends in Bogotá here.

Posted March 2024.

Contact me on colombiacorners@gmail.com

Other related posts on security on Colombia Corners are:

Colombia’s Cocaine Conflicts – report of recent travel to coca growing villages in Nariño.

Is Colombia Safe? – some security context and advice for visiting Colombia.

The Lowdown on Colombian Narco-Subs – a look at the maritime smuggling routes.

Jamie Garzon; The Day the Laughter Stopped, – how Colombia’s popular comic was murdered with state involvement.

In the Shadow of Los Pachencas – first hand account of a foreigner’s run-in with the criminal gang of Serrania de Santa Marta.

“It’s the (Narco) Economy, Stupid” – essay on how cocaine impacts Colombia’s economy.

Killed in the Darien Gap – story of a Swedish tourist executed by an armeg group while tryng to hike to Panama.

Homicides in Latin America

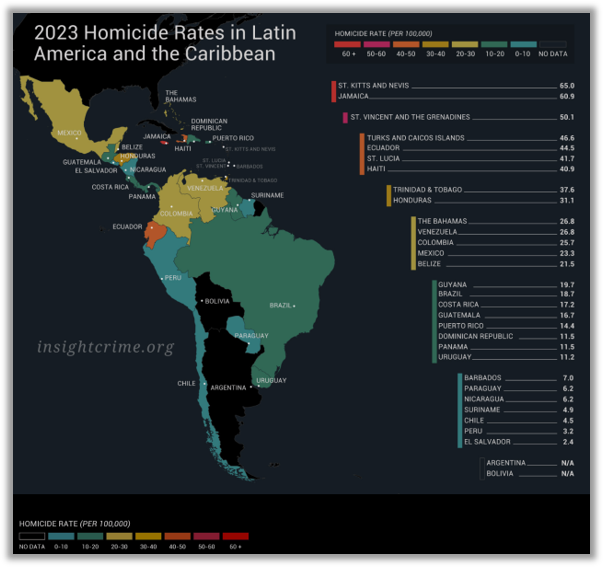

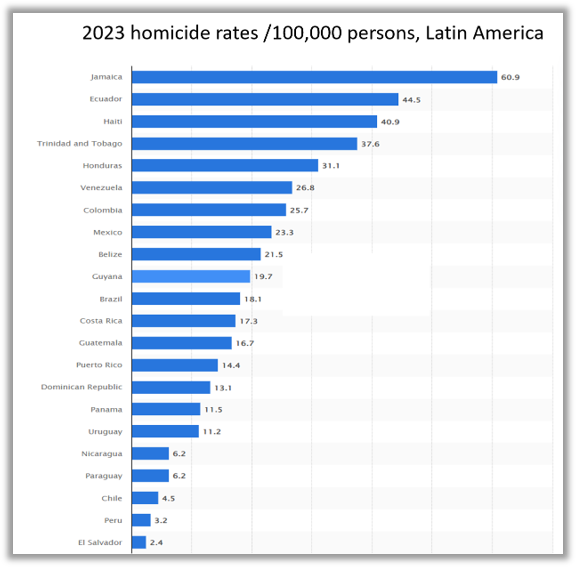

The region of Latin American and nearby Caribbean islands has the highest regional homicide rates in the world, with an average of 20 murders/100,000 persons in 2023. Much of this carnage is related to drug cartels, mafia syndicates, gangs and militia, that alternately cooperate, collude and compete for the control of illegal markets.

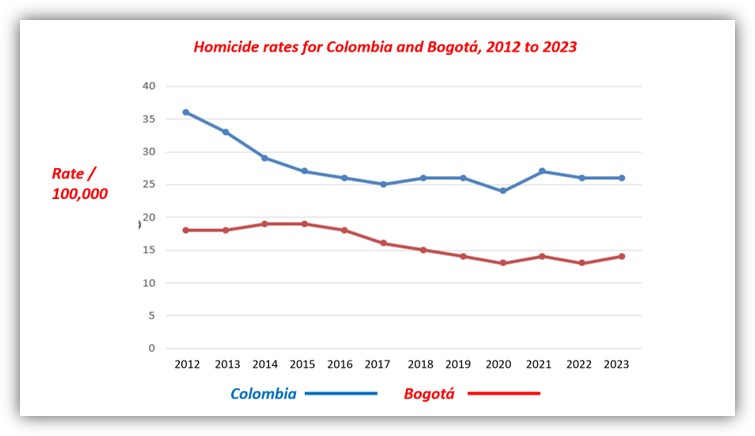

Colombia’s killings saw a small decrease in 2023, in line with a10-year trend, but still clocked 13,515 intentional homicides 27 homicides/100,000 persons). This rate is roughly five time higher than the USA rate for 2023 (5.5/100,000).

Regionally, this puts Colombia is in twelfth place in terms of insecurity, behind Ecuador, Honduras, Venezuela, and a bunch of small, dodgy, Caribbean islands.

The stand-out result is Central Amercia´s El Salvador that has lowered its homicide rate from a staggering 103 per100,000 in 2015 to under 3 per 100,000 in 2023, due to a controversial crack-down on gangs that has jailed 2% of the adult population.

Ecuador meanwhile is riding a crime wave and 44 per 100,000 homicide rate, sparked by a state war with cocaine gangs backed in part by their Colombian and Mexican counerparts, and Albanian gangs moving into South America.

The excessive homicide rates in small Caribbean islands reflects their continued importance in shifting cocaine, laundering money and dishing out passports to dodgy customers.

According to an UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime) analysis, more effective law enforcement in Latin America, and arrests of gang leaders, can perversely create more conflict as younger and more violent gang members take over operations. And some some governments – Mexico for example – allow powerful cartels to dominate swathes of the country (a kind of ´Pax Mafiosa’) in return for keeping crime rates down.

The Math on Murder…

Still, overall, homicide data gives the best insight into insecurity. I’ve used National Police data certified by DANE, the Colombian statistics agency. Other crime data is underreported – kidnappings, for example, where a ransom is paid – or street robbery which weary citizens often don’t bother to report.

Then there is also the paradox whereby a more effective police force will attract higher public trust – and therefore more cases are reported. This could be happening in Bogotá with renewed trust in the police force after an all-time low in the street riots of 2019/20. Hence the ‘crime wave’ could be better policing.

For various reasons, homicides still give us the best overview. Murders are also a window on gang wars, fights for territory, tussles between armed groups (ex FARC, ELN or ex paramilitary), cocaine production and exportation, and control of crime corridors down to street level.

Of course, homicide data can also be manipulated: ‘disappeared’ people will not show up in the data, nor killings in backwater communities. Some countries manipulate their data (Venezuela) or fail to publish it at all (such as Bolivia and Argentina in 2023).

A standard presentation for homicides is the rate of intentional killings per 100,000 people, allowing a comparison relative to the population.

This might create a figure higher than the actual deaths in small island nations, i.e. tiny St Kitts and Nevis (55,000 folk) with a homicide rate of 61/100,000 (one of the highest in the world) but only 31 actual killings. Mexico meanwhile has a huge amount of murders – close to 30,000 in 2023 – but spread over 128 million people giving a lower rate of 23/100,000.

Comparing Colombian Departments

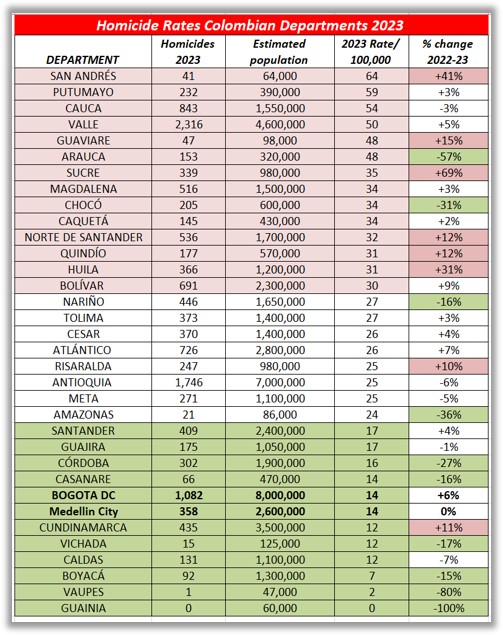

Topping the homicide rates is, surprisingly, the palm-fringed island of San Andrés, which lies far away off the coast of Nicaragua but sits on lucrative maritime routes for drugs and human trafficking across the Caribbean, with gangs vying for control. The high stats shouldn’t put you off visiting, as tourists are still relatively safe there, see my recent posts on diving in San Andrés and the nearby quaint Providencia Island.

The next three bad boys are Valle, Cauca and Putumayo, three departments encompassing mountains and lowlands with high presence of armed groups (mostly ex FARC dissidents), coca plantations, cocaine labs, trafficking routes and the host of problems that come as part of the package. Ditto Guaviare and Arauca, the next two on the list.

The surprise at 7th spot is cute Sucre, with its capital Sincelejo, which straddles the rugged Montes de Maria, an historic redoubt for guerrillas, currently caught in crossfire between infamous ex paramilitary Clan de Golfo (or AGC, Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia, as they auto denominate) and another break-away para group Los Norteños, battling to control smuggling routes.

Also with unexpectedly high homicide rates are Quindío and Huila, usually calmer places, but both on the radar of armed groups as cocaine smuggling routes shift inland from the traditional coastal exits.

The rest of the table is as we expect it, except for the remote border areas of Vaupes, Guainía, and Vichada; by location (bordering Venezuela and Brazil) these should be dangerous zones but are only registering a handful of homicides: I suspect killings are not being reported.

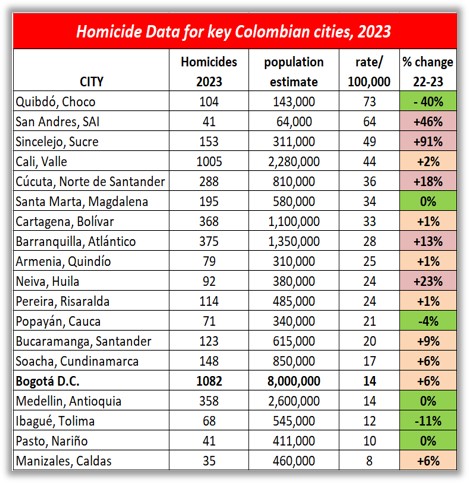

Bogotá vs Medellín vs Colombian Cities

Colombia’s two biggest cities compete at all levels, and this debate echoes among expat communities who in parallel defend their adopted cities. In terms of security, it’s hard to pick the cities apart; both have ‘good’ and ‘bad’ areas, with similar murder rates, and are probably equally un/safe for visitors depending on your own risky (or not) behaviour.

Bogotá has 1,082 homicides last year, which is a 6% rise compared to 2022, with a rate of 14 homicides/100,000, half the national average. Medellín had 358, giving the same 14 / 100,000 adjusted for population, similar to its 2022 figure.

In 2023, most other cities saw similar homicide rates to the previous year, except for Sincelejo, capital of Sucre, and San Andrés, see my comments above.

Neiva, Huila, also stands out with a 23% increase, down to incursions in the area from dissident ex-FARC groups now known as the EMC (Estado Mayor Central) in on-off peace talks with the Colombian state.

Cúcuta and Cali continue to be insecure, as do the areas and towns surrounding them, and the main coastal cities (Cartagena, Barranquilla, and Santa Marta) are also dominated by armed groups, though safe for tourism with caution.

Both Bogotá and Medellin remain among the safer cities in Colombia in terms of homicides, along with Manizales and Ibague. Note that Pasto city has a low death count, but surrounding Nariño Department can be highly insecure, particularly the Pacific Lowlands (see my post from there Colombia Cocaine Conflicts).

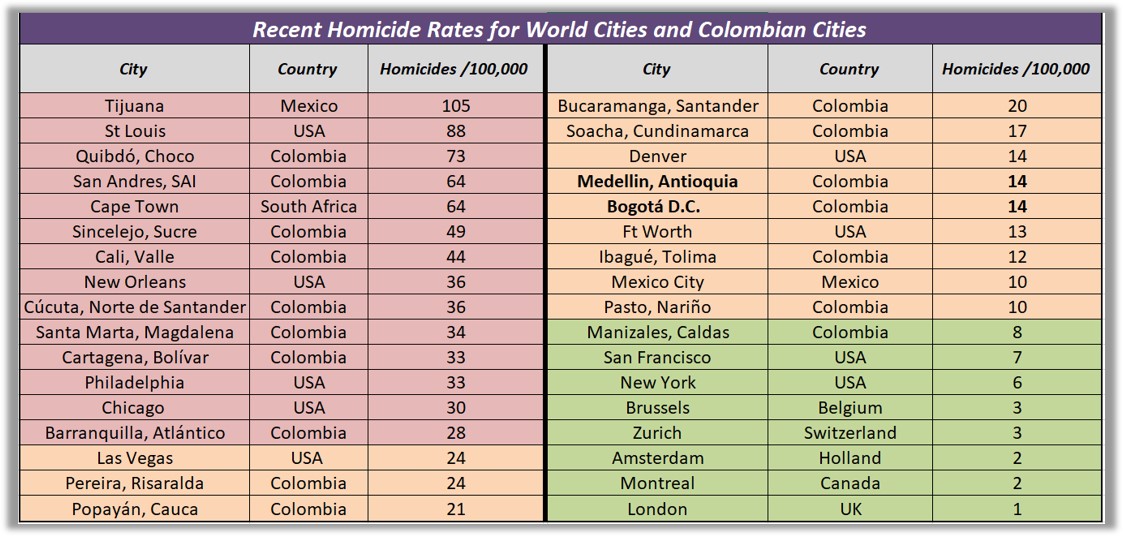

Colombian Cities vs The Rest of The World

Most travellers want a feel for safety in Colombia before they arrive, so it can be useful to compare homicide rates with other major cities you already know, see the chart below. Most Colombian conurbations score better than New Orleans. Just about everywhere in Colombia has a lower murder rate than St Louis, Missouri. Bogotá and Medellín are around as safe as Denver and Fort Worth in terms of homicide rates, and Manizales is almost up there with New York and San Francisco in terms of safety.

Nowhere gets close in security to most European cities; the people of the Americas are destined to kill each other in greater numbers than on other continents, it seems.

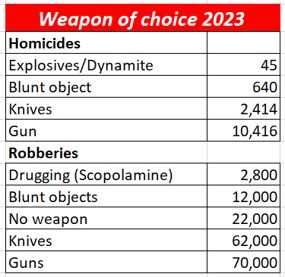

Murder methods

Official murder stats give scant details, and a very short range of ‘killing methods’:

- Arma Blanca/Cortopunzante (knife or sharp weapon)

- Arma de Fuego (gun)

- Contundente (blunt object)

- Artefacto Explosivo/Carga Dinamita (a bomb, or explosión in combat setting).

Right is a table of weapons of choice for killings and robberies 2023:

Armas de Fuego top the list for robberies and killings, which suggests guns are easy to get. Some will be armas traumaticas, gas-guns firing rubber bullets for sport or self-defence, supposedly non-lethal, but capable of killing at close range (which is why Colombia is now demanding registration of the hundreds of thousands being held by private citizens).

Who’s Killing Who? And Why?

Raw police data gives few insights to the ‘who’ and ‘why’ of Colombian killings. The geographic location gives some clues: for example, the ‘explosives’ deaths coincide exactly with coca growing regions, which chimes with the facts that armed groups protect coca fields with anti-personal mines and booby traps. Likewise, the violent departments of Cauca, Putumayo, Norte de Santander and lowland Antioquia, with weak or absent state presence, have overlapping armed groups clashing over drugs, illegal mining, and human trafficking routes.

No murder is justifiable, but that said, the reality is that the majority of Colombian killings are dog-eat-dog events between gangs and armed groups, often the victims being young males caught in the cycle of criminal violence.

According to UN (OCHA) data from 2023, at least 844 ‘protected people’ were assassinated in various circumstances, and Colombia’s Peace Courts (the JEP) detected 3,320 ‘selective killings’, i.e. people gunned down without a direct robbery motive. These killings often take place in broad daylight with killings done with high powered pistols by sicarios (hitmen) mounted on motorbikes.

Many such sicariato events are gangland killings between know criminals, though a recent case of a business auditor killed by a professional hitman in a wealthy barrio in the north of Bogotá caused consternation.

Other victims are:

- Women killed by men, often their partners or ex-partners, in 2023, at least 971 females were murdered, of which 483 declared as femicides (also see below).

- Youths killed in riñas, bar fights or street scuffles, often involving knives.

- Dozens of innocent business owners and workers killed by extortion gangs.

- Children killed by the stepfathers, several cases per year.

- In 2023, at least 181 social leaders were assassinated. Some are tangled up in illegal activities, others targeted for resisting the dominance of armed groups.

- 303 persons died in massacres, usually related to organised crime and armed groups, see more below on mass murder events.

- 50 troops from the armed forces were killed in operations.

Deadly Protection Rackets

Some targeted murders are linked to extorsion, which is widespread in Colombia, with criminal gangs often extracting protection money from local businesses as a sideline to running drugs. It’s a deadly racket: local gangs punish anyone not paying, partly to enourage the rest. These can take the form of attacks on properties – theft, fire or smashed windows – but also kidnappings, torture and targeted killings of business owners.

Some surveys have shown that most businesses in Colombia paid some form of protection money – some see it as the price of doing business – but it stifles the economy as well as the human toll. When I lived on the coast it wasn’t unusual for a hitman to toss a live grenade through a shop front to force the owner to pay. Bystanders were maimed or killed as a result.

Police data shows a 12% increase in extorsion nationwide in 2023, with a whopping 27% rise in Bogotá, with a survey of the capital’s businesses showing at least 10% of owners being facing demands for money. A worst case scenario is when rival gangs fight for territory putting shops and small businesses in the crossfire; gangs not only insist you pay them, but will also kill you for paying their rivals.

Extortion Hotspots

Many small businesses prefer to pay rather than risk a bullet, and rarely trust local police to protect them (some cops are in on the squeeze), despite regular campaigns by the city authorities to denounce the crime. For this reason, it’s under-reported in crime stats, though some independent data shows over 10,000 extortion cases reported for 2023 with hotspots:

- Antioquia and Medellin with 1,797 extortion cases.

- Atlántico and Barranquilla with 1,303 cases.

- Valle and Cali with 1,100 cases.

- Norte de Santander and Cúcuta with 549 cases.

Official data does not categorize ‘extortion victim murders’, though GAULA (specialised police units) stated that 10 business owners were killed in Bogotá in 2023 by extortion gangs.

The first two months of 2024 saw a rash of extortion murders in the capital, some examples:

- Bogotá, 10 January, 2024: business owner of auto spare parts shop shot dead for not paying protection money to ‘Pedrito and Moises’, criminals linked to Los Satanás gang.

- Soacha, 28 February, 2024: bus driver shot dead in his vehicle by hitmen who left a note demanding transporters pay extortion money to Los Satanás gang

- Bogotá, 7 March 2024: one person dead and four injured when a hitman opened fire on a local butcher shop that ‘refused to pay protection money’ to the Los Satanás gang.

Enter Los Satanás

Extortion in Bogotá last year was spearheaded by two allied Venezuelan street gangs, now resident in the city, El Tren de Aragua and Los Satanás, the Satans. Even after 17 gang members and several crime bosses were captured the threats continued from jail – some Colombians call their prisons ‘Crime Call Centres’ – as inmates get cell phones supplied by corrupt guards.

To the shame of the prison authorities, the leader of Los Satanás – himself known as ‘Satanás’- continued to make threatening calls even after being banged up in a ‘high security prison’ in Santander and had to be moved again to a clink in Valledupar.

Then, as is typical of Colombian crime gangs, his underlings took over the gang with alias Pedrito organising threats and killings of bus and taxi drivers into 2024.

Mass Murders

Colombia doesn’t suffer from US-style shootings whereby gun nuts empty their assault rifles into innocent bystanders, but does have plenty of conflict massacres, defined as three dead or more, often from combat between gangs and armed groups, or planned killings targeting rivals.

Victims can be civilians, often social leaders or anyone standing in the way of cocaine profits.

Yearly numbers are surprisingly consistent in Colombia, with think-tank Indepaz recording around 90 per year since 2020, with between 300 and 400 victims. During 2023, Colombia recorded 93 massacres claiming 303 victims, slightly down on previous years.

The 2023 data shows Valle Department had 42 dead in 13 massacres, mostly in towns like Palmira, Buga and Tulua. large towns close to Cali. It’s a similar story in Antioquia with 39 dead in 12 massacres, but mostly smaller towns or (Medellín had none) and Atlántico (Barranquilla areas) with 30. Bogotá recorded 4 massacres with 14 dead.

That these massacres often play out in rural areas is a reminder that organised crime penetrates most corners of Colombia.

Headline news – drugging deaths

We can’t look back at 2023 without mentioning the seven reported deaths of foreign tourists in Medellin, Antioquia mostly related to ‘devil breath’, ‘burundanga’ or scopolamine drugging of sex tourists that hooked up with young Colombianas on dating apps such as Bumble, Cupid and Tinder. Several more deaths were reported in the first two months of 2024.

Tourists are doped to kidnap and rob them, but sometimes the dosage is high enough to kill them. Other victims are tortured to give out bank card details etc, and some beaten to death. I covered this extensively in my recent post Burundaga: It’s Bad and It’s Back, which I urge anyone visiting Colombia to read.

Since then there have been several more deaths of tourists in Medellin including the brutal killing of US citizen and comedian Tou Ger Xiong – he was beaten and thrown off a cliff after posting in December after posting on-line about all the Colombian women he had met.

The Youtube channel of DC Born Rob – Erasing Borders – updates on crime in Medellín, here he announces an 18-year-old female is jailed for the murder of a 55-year-old Texan tourist in his hotel room in November, 2023 .

Embassy Alert

A rash of fresh killings in the first two months prompted new embassy warnings and local law enforcement to announce what we knew all along: these deaths are related to organised crime gangs. Worryingly, the drugging deaths in Medellin seems to have heralded a new era of foreigners being targeted for crime and spreading to cities like Bogotá. It is worth mentioning that Colombians have been routinely doped with scopolamine and benzo drugs for decades, though stats are hard to come by: forensically, scopolamine poisoning is hard to detect and victims often too confused to report the crime.

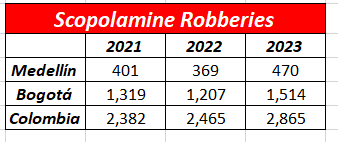

For some reason escopolamina deaths are not segregated in homicide data, but cases of drugging robberies are recorded, see the table right.

Numbers are probably under-reported but show a slight rise in 2023. Both Bogotá and Medellin have a similar drugging rate (18/100,000 persons) in 2023, suggesting the drugging problem is present in both cities. ‘Scoping’ is more mediatic in Medellin because of the targeting of foreign sex tourists there but affects many more Colombian victims in both cities.

Because of the tourist attacks, in March 2024, Medellin authorities announced a new “911” hotline that will connect tourists in danger to a translator and connect them to the national 123 Colombian emergency line.

Meanwhile in 2024, Medellin is pushing back on sex tourists, pornographers, abusers and paedophiles; a 48-year-old US citizen was arrested in March accused of drugging then abusing underage girls and two other expats arrested or deported for sex crimes the same week.

The Suitcase Killings

Of note were in 2023 were two horrific killings of young Colombian females, with both bodies found bundled suitcases, and in both cases foreign tourists accused of the murders and fleeing Colombia.

In January 2023, Bogotá was in shock over the killing of a popular young DJ , Valentina Trespalacios, strangled by her ‘boyfriend’, US citizen John Poulos, who was caught on CCTV moving her body, stuffed and bound in a suitcase, before he flew to Panama and tried to board a flight to Turkey. After a dramatic airport interception, he was hauled back to Bogotá and is now facing trial and life in prison if found guilty.

In March 2023, after a year of delaying tactics by his lawyers, Poulos pleaded guilty to the ‘lesser’ crime of homicide, though state prosecutors are pushing for full femicide charges (which carry a longer prison sentence) and are presenting evidence the murder was pre-meditated.

Later in 2023, a 50-year old US-born man Jesse Wiseman was hiding out in his adopted country of Canada after being accused of killing of a 20-year-old single mother in Medellin, also stuffed in a suitcase found in his rented apartment. According to this remarkable video from DC Born Rob, a Canadian citizen saw Wiseman on a Canadian train and alerted police – who did nothing.

Will Poulos get sent down for femicide? Will Wiseman get extradited back to Colombia to face trial? The fate of the two foreigners will be closely watched in 2024.

Other Femicides

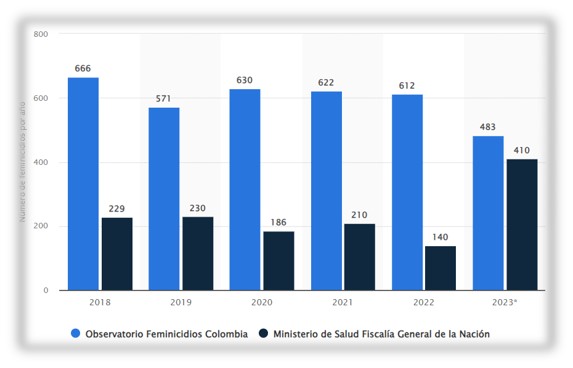

These two high-profile suitcase killings were just two of971 female murder victims last year, according to police data a reduction of 7% on 2022. Of these, around 483 were declared femicides by NGOs, and 410 officially stated as such (there are various definitions of ‘femicide’).

The general trend is downward, but with more murders of females recognised as femicide, reflecting a national impetus to call out these crimes and do more to prevent them, such as Bogotá´s ´Ruta Única de Atención’ Purple Line hotline for women at risk, and specialised female police units.

Cocaine as a driver of conflict

In 2023, cocaine use was at a global high and rising. This despite media reporting of Colombia’s ‘coca leaf price crash’, suggesting the bottom had fallen out of the cocaine market in 2022 and Colombia’s president even suggested fentanyl was replacing coke as the ‘preferred drug’ for gringos and Europeans (anyone with a passing knowledge of drugs and users knows this is not a likely scenario).

Yes, there was a coca leaf price crash, but not related to reduced demand. In fact, intense combat between armed groups in coca-growing areas had made it highly dangerous for farmers to markets coca for processing, as highlighted in my post Colombia´s Cocaine Conflicts 2023.

And sure enough, UNODC’s own 2023 analysis showed a worldwide surge in cocaine demand, and a parallel rise in coca plantations and processing, more foreigner actors in Colombia and next-door Ecuador (Mexican and Albanian drug gangs).

Add to this the emergence of new markets (Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe) demanding higher quality cocaine, and a new craze for crack cocaine in Western Europe…UNODC estimates 22 million cocaine users in 2021 with a strong upward trend…

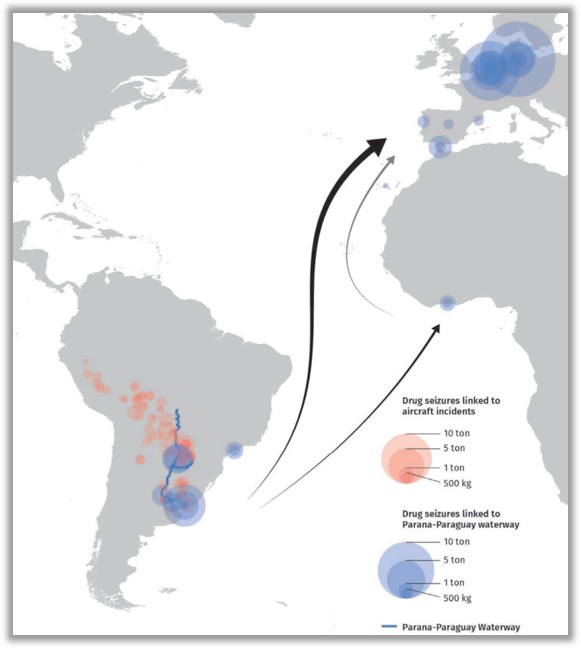

New Smuggling Routes

As well as new players, the continuing cocaine boom demands new routes, in the case of Colombia through southern and eastern borders (to Venezuela, Brazil and Ecuador) to Atlantic ports in far-away Argentina, spreading insecurity across the Amazon as well, as highlighted by recent reports by Amazon Underworld, at the same time squeezing the traditional routes through the central America and the Caribbean.

Gang terror in the Caribbean has put tiny St Kitts and Nevis in the Leeward Islands at the regions highest murder rate – 31 killings in a tiny population of 47,000 – closely followed by Jamaica, St Vincent and the Grenadines, and the Turks and Caicos.

Ecuador, traditionally seen as a safe haven in South America, is now gripped by panic and 8,000 murders in 2023, a rate twice as deadly as Colombia.

Colombia’s lower homicide rate signals it’s more mature approach to cocaine wars; many Colombians look at Ecuador and say ‘Yep, we’ve been there before’. In simplistic terms, other areas of Latin America are facing the same violent turmoil partially overcome by Colombia in past years.

Kentucky Fried Cocaine

The reality behind this is that Colombia is still the world’s number one cocaine exporter, creating huge profits and possibilities; even if one cadre of old narco-guerrilla/paramilitaries retires under some negotiated ‘peace process’, another generation will step up to fill the vacuum.

Production and trafficking of cocaine requires territorial control to grow coca plants, process cocaine, and manage land, sea and air corridors where cartels can send out the mercancia and bring in cash, guns and precursor chemicals.

Like many business models, the cocaine trade in Colombia has shifted towards a ‘franchise’ model, like MacDonalds and KFC, with many small ‘service providers’ contributing to the bigger business; local gangs are recruited to fill gaps in the cocaine supply chain, while maintaining their traditional territorial crimes such as extortion, robbery, human trafficking, and local drug dealing.

Totally Taking the Peace

Every newly elected Colombian president embarks on a ‘peace process’ with a major armed group perhaps hoping, like Santos, to get a Nobel Peace Prize. Current left-wing President Petro is going a step further with his ‘Total Peace’ initiative, a bold move to engage all of Colombia’s armed groups – including some unsavoury criminal gangs – in an overarching strategy to end conflict.

Key to this were rolling ceasefires as a carrot to bring them to the negotiating table. In effect, in some rural conflict areas of the country, the Colombian military stepped back from combat operations.

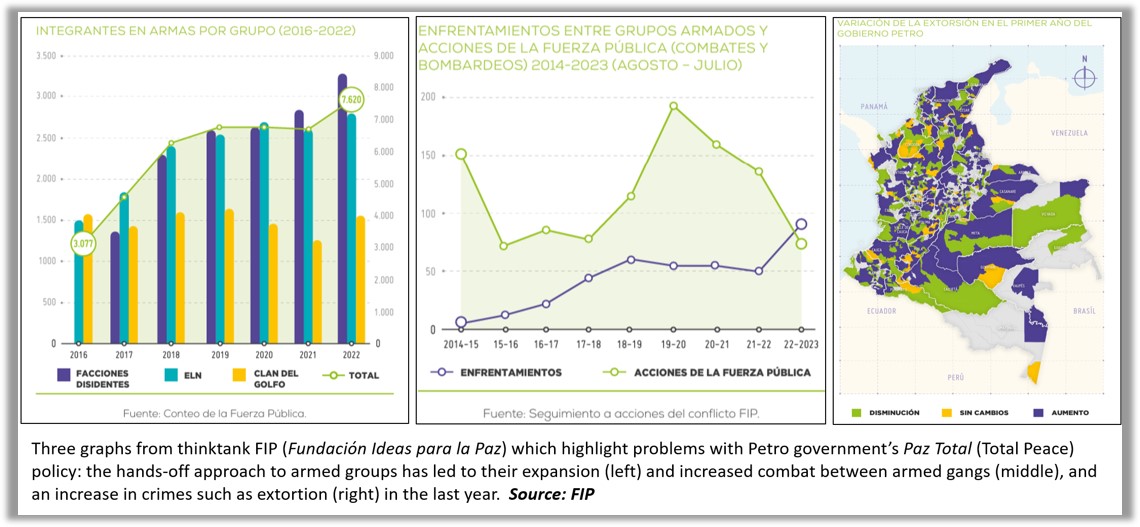

Petro’s everything-everywhere-all-at-once approach has had mixed results in 2023, according to thinktank FIP Fundación Ideas para la Paz. At first glance, the year closed on a positive note with a decrease in two key ‘humanitarian impact indicators’:

- forced displacement down by 24%

- killings of social leader down by 15%

But, surprise, surprise, behind the scenes the armed groups and gangs used an passive state military to further their own ‘prime objective of enlarging their criminal control’, according to FIP.

No longer distracted by fighting state forces, the armed groups battled between themselves to gain territory while growing their ranks. Such inter-group conflicts rose by 54%, according to FIP, and gang-related activities like extortion, which I outlined above, have spread alarmingly into new urban areas, such as Neiva in Huila, and new areas of Bogotá.

Are the Armed Groups Gaining?

The FIP analysis of the Total Peace initiative in 2023 concludes that the armed groups and gangs are ‘winning the game’.

According to FIP, the good-news stats from last year mask a worrying reality that armed groups are expanding and controlling more territory. This, coupled to the global cocaine boom, puts Colombia in a precarious position.

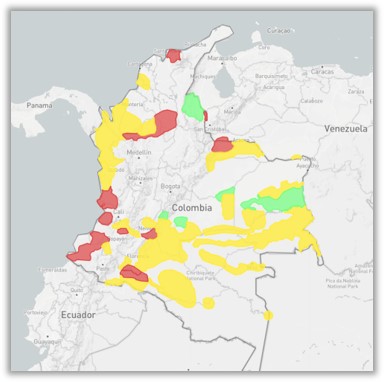

In its report Los Grupos Armados Ganan con Cara y con Sello, FIP maps out conflict dynamics across the country with the categories:

- Dominate (one armed actor has majority control of the zone)

- Coexist (two or more armed actors in alliance or truce).

- Dispute (two or more armed groups in conflict).

Not surprisingly, the disputed areas see most violence and overlap with high homicide rates. You can find the online interactive version of their map here.

Note that conflict patterns don’t fit exactly into department boundaries, not spread across all the department: i.e. most of Antioquia is much safer than its north-east corner. And some departments might contain various dynamics within the boundaries. Cities like Cali, Popayan, Neiva and Pasto are firmly on the tourist trail, but Valle, Cauca, Huila and Nariño (their respective departments) look bad on the map thanks to conflict in rural areas.

What Next?

Probable scenarios for Colombia homicides in 2024:

1: Small-scale conflicts will flare up around Colombia as established armed groups tussle over territory and their share of the cocaine boom. This will happen mostly in rural coca-growing areas. New corridors and exit points will make border areas even more insecure, and bring conflict to previously peaceful cities and towns that lie along transit routes.

2: Drug wars will spill over into urban areas and cities like Bogotá as street gangs vie for dominance and to ally themselves to the big cartels and get their slice of the cocaine pie. Local gangs will need to prove themselves in cruel and inventive ways, leading to crime waves in urban areas.

3: Respect for tourists is eroded by sex pests, paedophiles, and homicidal gringos. Gangs, particularly in Medellin and Bogotá, increasingly see foreigner visitors as targets. Avoid risky behaviour.

None of this should put you off coming to Colombia in 2024; the country has lots to offer, and most visitors have a great stay. But I hope this post has shown, there are still plenty of risks out there and as long as the world consumes cocaine there will never be peace in this corner of Latin America. Stay safe.