Is Bogotá safe? 2023

“I’m visiting Latin America. Is Bogotá safe?”: the question pops up regularly on social media.

Colombia’s capital is a mega-city of nine million people and spread over 1,600 kilometres squared (600 square miles) with extremes of poor and rich. Parts of the city are very dangerous, others much less. According to recent data, Bogotá is safer than most other cities in Colombia (including Medellín) – but is still a large gritty city with plenty of crime.

Your safety also depends on who you are. A long-term settler? A backpacker? A digital nomad? A fluent Spanish speaker? With friends or with a family? A drummer with the Foo Fighters? Lifestyle factors can affect your personal security as much as the city around you.

I’ve analysed publicly available crime data from 2022, which represents recent trends, and mapped this against Bogotá’s districts and areas of the city where overseas visitors and tourists stay. I’ve also done an update for 2023.

July 2023. Related posts:

- Burundanga: it’s bad and it’s back. A deep dive into drugging.

- Killed in the Darien Gap. A tourist murdered by armed groups.

- Colombia’s cocaine conflicts, 2023. Notes from the frontline of the conflict.

Contact Colombia Corners by email to colombiacorners@gmail.com

How to measure insecurity?

Like most cities, Bogotá is a mix of residential barrios, business districts, industrial zones and some green areas, all with their own level of threats, and all evolving in different ways. I’ve visited Bogotá regularly since 1994 and lived permanently in the city since 2011 and visit many areas of the city where I travel on foot, by car, and by local bus, and never been personally robbed or attacked.

That’s partly down to luck: crime is common here, I have witnessed armed robberies, many friends have been victims of crimes, and I follow social media and local news with daily alerts of murders and crime.

But how bad is it? In cities like Bogotá, crimes are underreported since many locals don’t trust the police. For this reason, I will start with HOMICIDE RATES (‘unlawful death purposefully inflicted’ measured per 100,000 of a population), which are the most accurately reported crime statistics in the city.

Killing statistics

OK, you say, but many murders in Colombia are dog-eat-dog killings between gangs, or conflict-related, or politically motivated that don’t directly target the average citizen, or tourist or visitor to Colombia. True: many killings are targeted, and armed groups and gangs tend to avoid collateral damage.

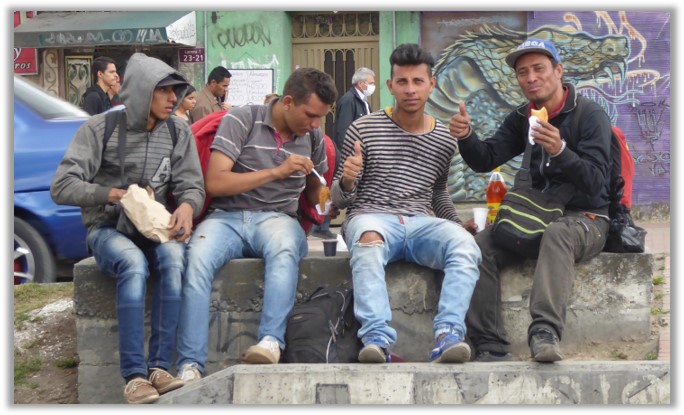

The fact is though, that in Colombia criminal gangs exert strong territorial control in all cities and many large towns, often through complex network of associates and smaller gangs, down to street level with pickpockets, muggers, thieves etc all forming part of a larger mass. Even beggars, homeless, car parkers, recyclers and informal street sellers are coerced into relationships with gangs (though often as an act of survival). Unfortunately, some police and state security forces are also corrupted into criminal collaboration.

So let’s assume that homicides, even if targeted and committed between gangs, are one way to measure criminality and therefore overall insecurity.

Homicide rates: Colombia compared with the Rest of the World

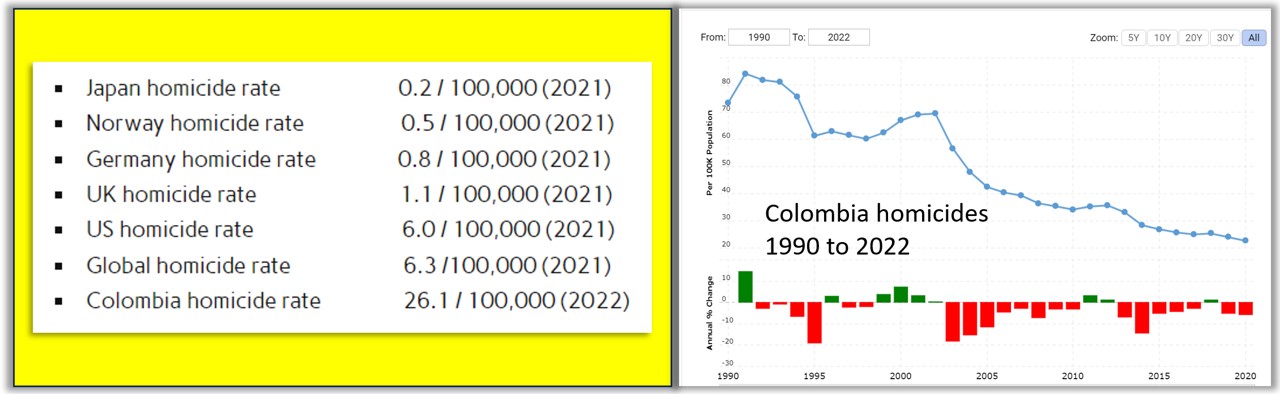

According to Insight Crime, Colombia recorded 13,442 homicides in 2022, that’s an average of 36 per day, and a rate of 26.1 per 100,000 population for the year. This is down from 26.8 per 100,000 in 2021. It’s worth noting that a thirty-year trend of decreasing homicides in Colombia from a peak of 80 per 100,000 in 1991, so the country is slowly improving.

Compared to the rest of Latin America, Colombia is on a par with Mexico, Ecuador, and Belize, and safer than Venezuela and Honduras. But worse than another 14 Latin-American countries.

As the table and graphs above show, Colombia is still a dangerous country compared to the rest of the world, and particularly Europe. In terms of homicides, we can say Colombia is: 4 x more dangerous than the US; 22 x riskier than the UK; 30 x more insecure than Germany. But Colombia is big, larger than France and Spain combined, and corners of the country, particularly rural towns in departmentos like Boyacá, can go years without a single murder.

Bogotá insecurity compared to other Colombian cities.

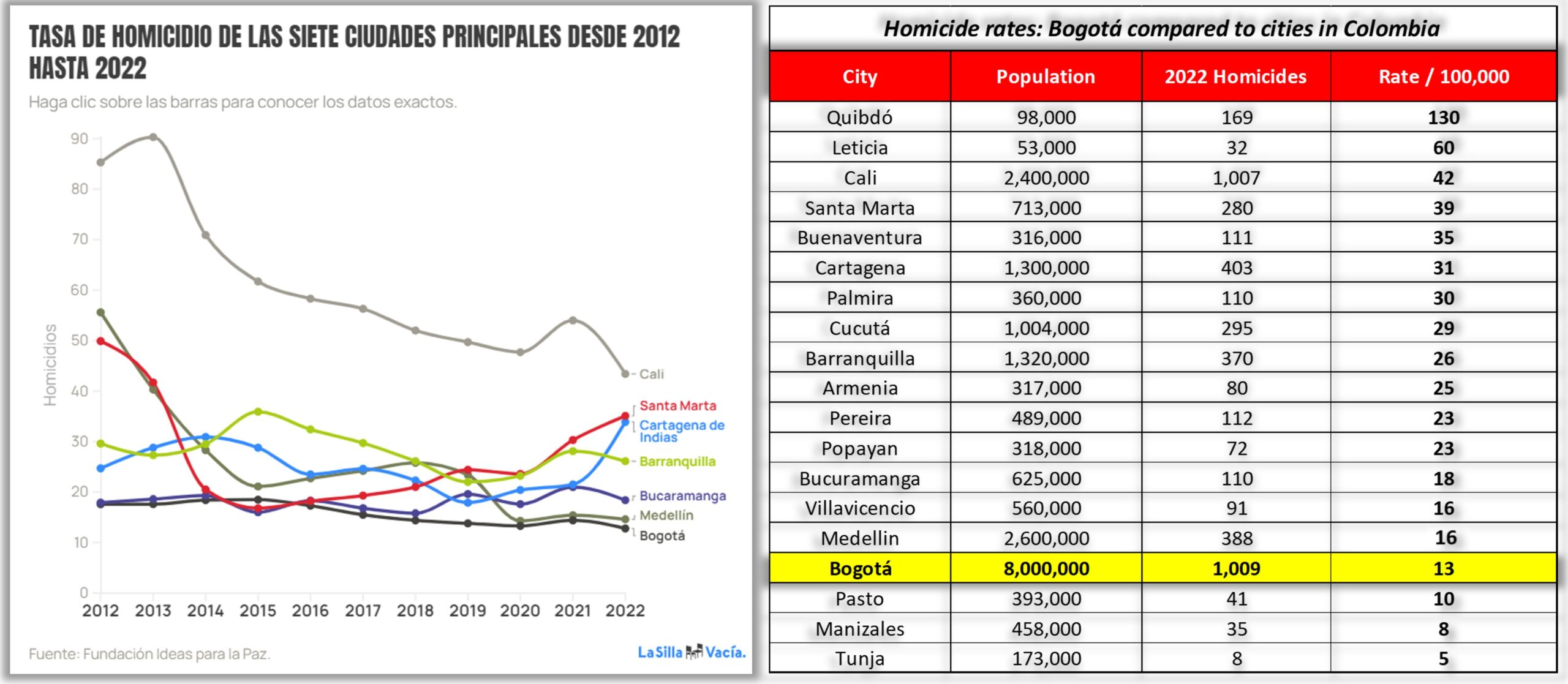

Perhaps, surprisingly, Bogotá’s homicide rate of 13 murders/pop. 100,000 in 2022 is way down the list in terms of homicide rates, and half the national average (26 homicides/100,000).

In fact, Bogotá fares slightly better than Medellin (16 homicides/100k) and the stable smaller cities like Pereira (23 homicides/100k) and Armenia (25 homicides/100k). Manizales, Pasto and Tunja are the only local capitals with a lower murder rate.

Bogotá relatively low homicide rate is unusual for a capital mega-city. There are several reasons for this:

- Because of its geographical location, Bogotá is not a major hub for cocaine and arms trafficking, in comparison to border or port cities (Buenaventura, Barranquilla, Cartagena, Cúcuta, Leticia, Santa Marta).

- The rural areas adjoining the capital city (Cundinamarca, Boyacá) are generally pacified with no regular presence of organised armed groups, in contrast with cities like Cali and, Popayan which are close to rural conflict areas.

- Bogotá has less residue from the powerful cocaine cartels that plagued Medellín and Cali in the 1990s (and still have their tentacles in those cities today).

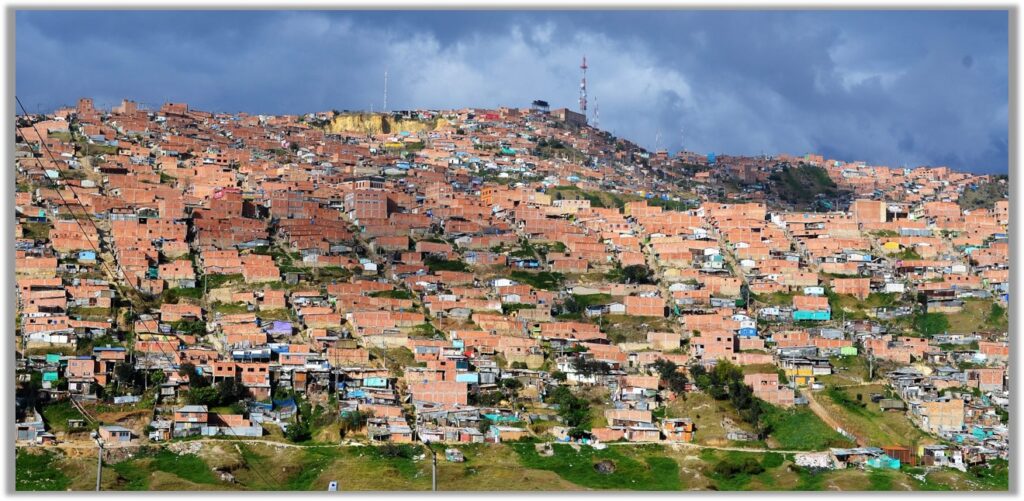

As a reflection of this, Bogotá is a huge receptor of people ‘internally displaced’ within Colombia, that’s to say families fleeing violence in other towns and rural areas.

Bogotá insecurity compared to US and world cities.

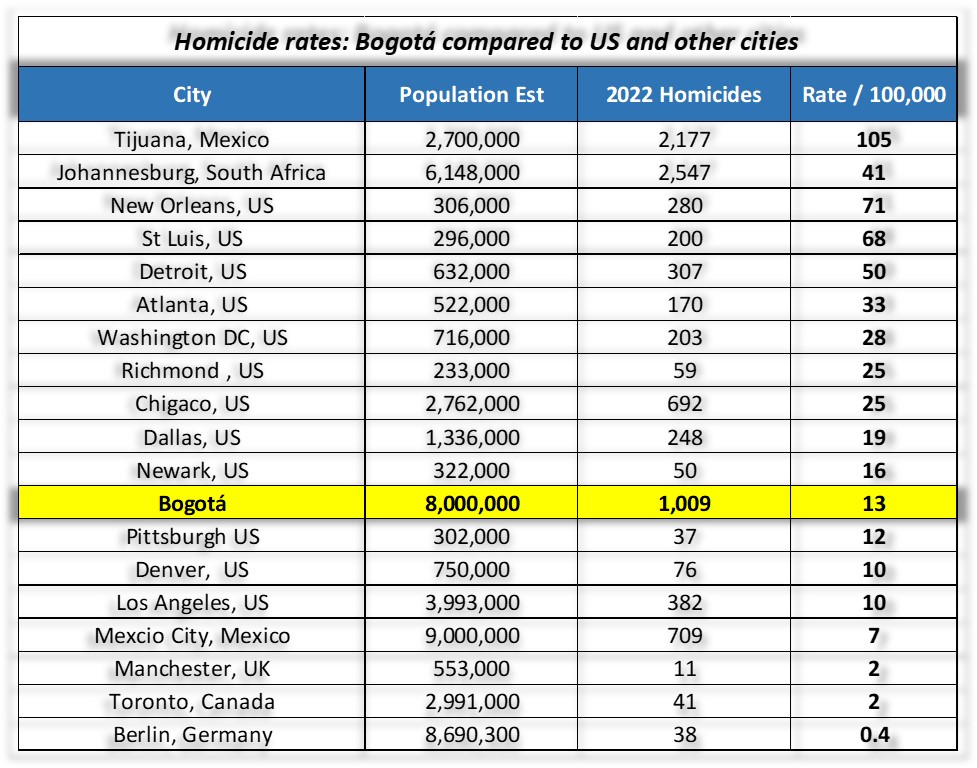

In terms of homicide rates, Bogotá is safer than many US cities and other worldwide mega-cities, though compares badly to European capitals. Your own perceptions of safety here may depend on where you travelled from: a visitor from Chicago or New Orleans be less nervous in Bogotá than, say, someone from Geneva or Berlin.

The Risk Mosaic

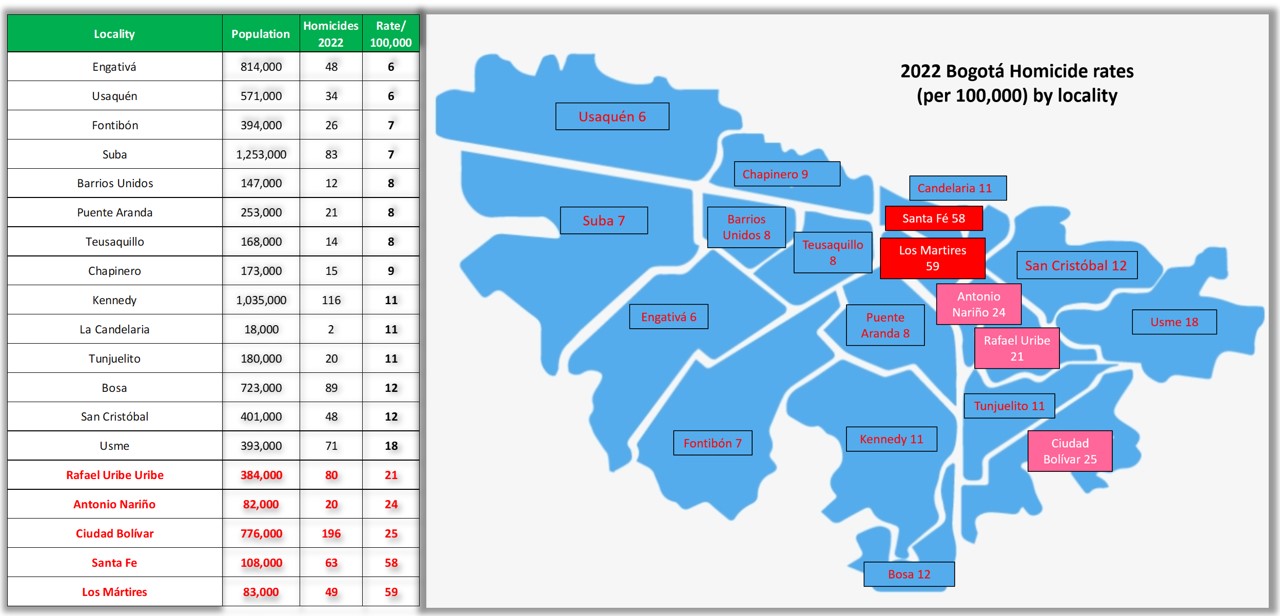

The map and table below show Bogotá’s districts with 2022 homicide numbers and rates. Local authorities usually just publish actual homicide numbers, I’ve calculated the rate/100,000 to account for the widely varying populations (some areas have 1 million, others less than 20,000) for a clearer picture.

The results are surprising; even gritty zones like Kennedy (12 homicides/100,000) and Bosa (11) are under the city average (13) when population numbers are considered. As expected, the most dangerous barrios are central and south, for example Ciudad Bolivar (25) which sprawls over the mountains south of the city (If you want to visit this are see my post Day trip to Ciudad Bolivar).

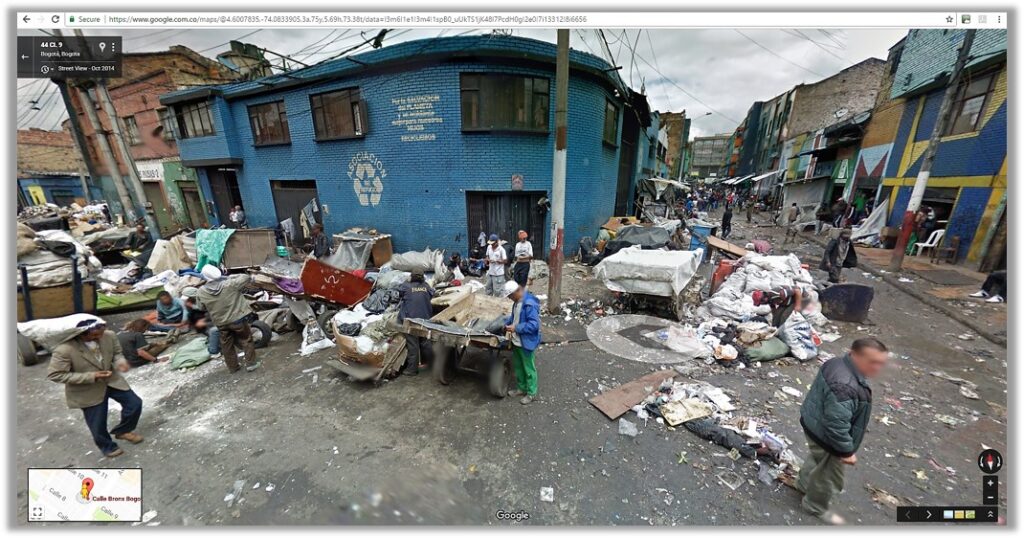

By far the most dangerous are the two small city-centre districts of Santa Fé (58) and Los Martires (59) two barrios which frame Colombia’s historic centre – Plaza Bolívar, the Capitolio Nacional and Casa de Nariño – but became inner-city sumps and the hub of the city’s drugs trade, prostitution and gangs, with for years had no-go zones like El Bronx and El Cartucho filled with homeless looking for their next bazuco fix. Various police operations have shut down hotspots like El Bronx, but gangs still flourish in the area. A recent tourist video of these areas appeared on Youtube: the ‘Bogotá they don’t want you to see’.

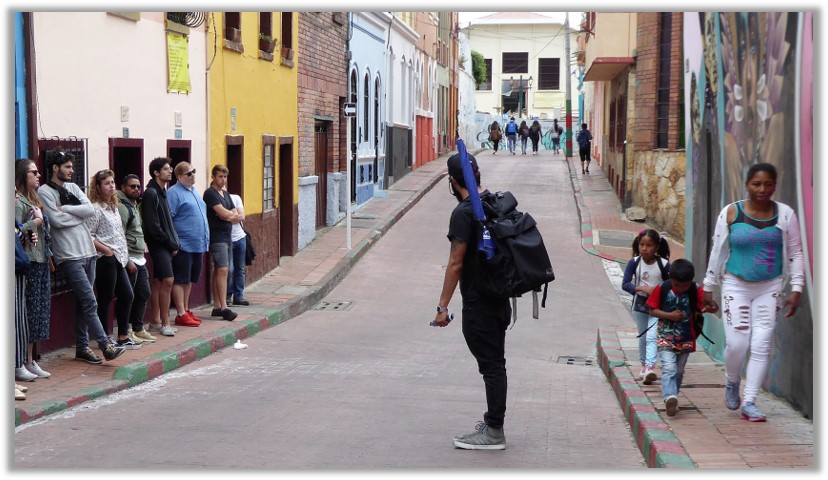

These dangerous districts are close to La Candelaria, another downtown barrio popular with tourists, and straddle main transport routes through the city (Avenida Caracas, Avenida 30-NQS and the eastern end of Avenida 26-El Dorado). La Candelaria is reasonably safe these days, or if you want to visit the zone, a good way is with the Graffiti Art Tour.

So where is safest in Bogotá?

Data shows that the north of the city is less dangerous, in terms of homicides, with upscale districts such as Usaquén (6 homicides/100,000) most popular for wealthier citizens, businessmen and diplomats. Middle class barrios like Chapinero (9), Barrios Unidos (8) and Teusaquillo (8) are more edgy but cheaper and popular with travellers and digital nomads.

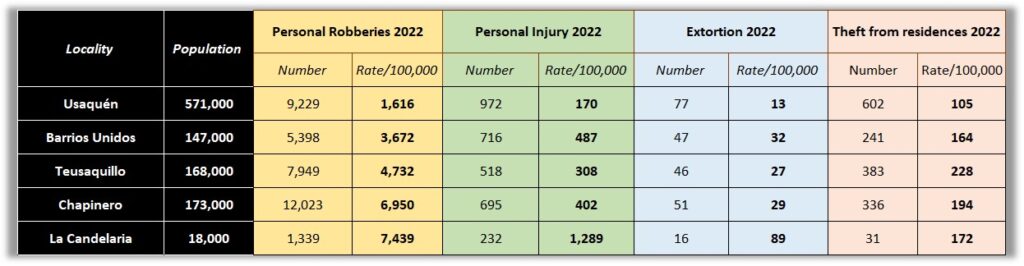

Homicides, though, don’t tell the full story; robbery, kidnapping and extortion are other violent crimes tracked by Bogotá’s Secretaría Distrital de Seguridad, Convivencia y Justicia (for some reason they don’t include rape and sexual violence in their on-line database). Mapping theft and robbery is more complicated because in the poorer barrios, victims are much less likely to report crimes, skewing the figures towards the northern areas. For this reason I’ve only plotted rates for some barrios, and only some crimes.

La Candelaria in the city centre has a very high rate of personal robberies (mugging and pickpockets), injury (probably related to physical attacks during a mugging), thefts and extortion. Chapinero also has a high level of mugging.

Usaquén, in the north of the city, is safest according to the data. This wealthy part of the city has many (armed) security guards and buildings and shops are well physically protected, and streets lit at night. Teusaquillo is a hotspot for house break-ins, which could be explained by its many smaller residential buildings that lack the resources for guards or good security systems.

Bogotá v Medellín

It makes sense to compare Colombia’s two major cities, and main receptors of longer-term visitors and migrants. Bogotá has a slighty lower murder rates than Medellín with both cities reducing in recent years.

In terms of street crime, Medellín is safer, with personal robbery and injury rates well below the Bogotá average, at 1,077 roberies/100,000 in 2022, and 180 personal injuries. This is as good as, or better, than Bogotá’s most upmarket Usaquén district.

So in terms of street crime, Medellín is safer than most of Bogotá, and most pople in the city feel more secure. However, the higher homicide rate does reflect more entrenched organised crime gangs, a hangover from Pablo Escobar’s grip on the city.

These mega-bandas are now known as the Oficina de Envigado and La Terraza, with many micro-gangs under their umbrella, which increases extortion and forced displacement in the city. These gangs also control and limit street crime as part of their territorial control. Conflict between gangs, or sudden efforts by city authorities to combat certain gangs, could quickly create a rise in insecurity. Bogotá’s criminal landscape is one of smaller groups constantly in conflict, with Venezuelan gangs like Tren de Aragua getting a strong foothold in the city in recent years, but yet to dominate the city.

One worrying statistic for Medellin in 2022 is that out of 388 murders, 9 were of foreign tourists (of which 5 were with druggings), reflecting the city’s reputation for activities such as sex tourism and high-risk hook-ups. which has created a spate of druggings. Similar drugging cases were recorded in Bogotá but without deaths. The last recorded expat death in Bogotá was a Chinese businessman in Barrio Modelia in 2021.

Crimes spree in 2023

January-June figures for 2023 show a 6% reduction in homicides in Colombia for the first 6 months of the year – but an increase in Bogotá, which went from 476 in 2022 to 529 in 2023 for murders during the same period. Robberies and other crimes also increased across the city, though Barrio Unidos saw higher peaks (from 3 murders in 2022 to 17 in 2023).

The rise in murders are from gang fights, such as the grim discovery in May 2023 of a ‘chop house’ in Chapinero where Tren de Aragua gang killed and dismembered some rivalssay city authorities. But all crime is rising, including reported cases of extortion, robberies and muggings, added to which are constant new media reports of daring daylight attacks my masked gunmen in cars in the north of the city during rush hour traffic.

Crime numbers reduced again in June, amid police claims of operations tackling gangs like Tren de Aragua, but it’s unlikely Bogotá will end 2023 with lower figures than 2022.

Choosing where to stay in Bogotá.

Of course, there are many variations within Bogotá’s districts: Chapinero, for example, covers a large swathe of the city and has some shady areas (around Avenida Caracas for example) and more secure zones (Chico, Rosales, Zona G)

Overall, the data shows a trend already known to long-term residents of the city:

- Usaquén has least crime – if you can afford to live there. Long term migrants and families will aim for this area. Northern areas of Chapinero (Chico, Rosales) are similar.

- Middle-class districts like Teusaquillo, south part of Chapinero and Barrios Unidos have low homicide rates but persistent street crime. Many long-term visitors, exchange students, digital nomads and teachers choose these areas. Note: 2023 figures are showing a marked increase in all crimes in Barrios Unidos, so that area is best to avoid for now.

- La Candelaria has a slightly higher homicide rate and much higher levels of robbery and personal assault, but is also the vibrant city centre, and has backpacker hostels, and is popular with budget travellers.

Of course some visitors to Bogotá go off the tourist trail and stay quite happily in the south of the city or in satellite towns like Soacha.

Weapons of choice

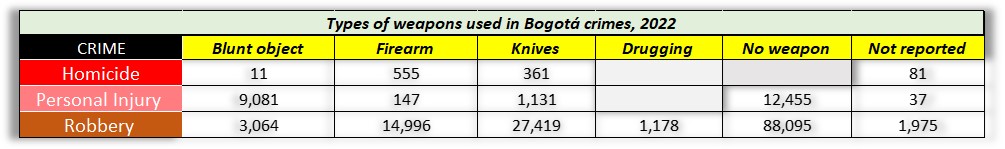

How are these crimes committed? The following table shows 2022 data for homicides, personal attacks and robberies.

As expected, knives and guns make up most of the homicide weapons, whereas most personal injuries are committed with no weapon (therefore fists or kicks) and blunt objects, suggesting many of these crimes are domestic or related to street scuffles (ie football hooligans).

Robbers commonly use firearms (15,000 cases) and knives (27,500) to threaten, and weapons seem widely available on the street; just in the first five months of 2023, police confiscated 70,000 knives and 417 firearms in Bogotá, mostly during routine stops at Transmilenio stations.

The high level of robberies where ‘no weapon’ is used (88,000) covers non-confrontational crimes common in Bogotá: pickpockets and sneak thieves stealing bags in restaurants. But could also include ‘snatch and grab’ attacks (motorbikers grabbing your cell phone in the street) where no weapon is reported though the attackers are likely armed.

‘Drugging’ refers to the common practice in Colombia (and in many parts of the world now) of attackers putting something in your drink, often scopolamine (known locally as burundanga) extracted from plants, or pharmaceutical drugs like Xanax.

Risks from drugging attacks are very high, including severe medical problems, sexual assault, rape and death from an overdose. I have written a post on drugging in Colombia called ´Burundanga; it’s back and it’s bad’. Anyone travelling to Colombia is strongly advised to read up on this risk.

The motorbike menace

Organised gangs commonly use motorbikes to commit crimes, following a long tradition started by the drug cartels and paramilitaries to use motorbike-mounted assassins to kill their targets, apparently first taught to cartel sicarios by ex-Israeli forces.

Gangs still use motorbikes for assassinations in all parts of the country, but also for street robberies in Bogotá. The robbers usually cruise the streets looking for targets – someone talking on their expensive phone – then choose their moment to mount the pavement with the bike passenger quickly snatching the phone and riding off.

Sometimes the bike passenger dismounts, threatens the victims with a gun or knife, while the motorbike circles nearby. These attacks are often in busy areas, in daylight, and can be swift and violent as the attackers are racing to get away fast. Recent variations are robbing car drivers in traffic queues, stealing other motorbikes, and mobs of motorbikes carjacking one vehicle.

Because of the mobility of these gangs, these attacks are common all over the city and can happen in the ‘safer’ areas up north, where luxury cars are more likely to be targets.

Levels of motorbike crime in Bogotá tend to come in waves as gangs rise up, then are dismantled by specialised police units.

Facing the threat

The above data shows a high level of armed robberies against individuals (around 115 per day across the city) with a relatively low homicide rate (around 3 per day, and many of those are gang related or targeted assassinations, so not cases of street attacks).

This points to the fact that people living in Bogotá are usually submissive in the face of robberies or other threats, usually complying with the attackers and quickly handing over valuables. ‘If attacked, don’t resist’, seems to be conventional wisdom in the city.

Perhaps this comes from a constant reminder – repeated on the news channels and social media – that criminals have guns and knives and will use them. As I write this, my neighbour is mourning her cousin who was stabbed to death last week; he confronted a bicycle thief outside a restaurant and was killed for his trouble.

The same week I witnessed an armed robbery in Teusaquillo when a motorbike rider pulled a gun on some pedestrians and took their phones and wallets. When one was slow to hand over his phone, the attacker fired several shots in the air. The victim quickly complied.

It is worth to note that Colombia has a low level of ‘civilian’ gun ownership, with an estimated 16 guns/100 persons in Colombia (compared to 120 guns/100 persons in the US). Of course, that many of those Colombian guns are in the hands of criminals who will use them with bad intent. This also means that robbers don’t expect their victims to fight back.

Of course, you do have some people turn the tables, such as a high-profile case of a doctor in the north of the city who was carrying a handgun (unusual in Colombia) and shot dead three muggers (they had tried to stab him first).

In other cases a bus passenger disarmed a robber, taking the attacker’s own knife and killing him on the spot and a cyclist targeted by four robbers pulled out a gun and shot one dead.

Such cases are rare though. Unless you’re packing heat, it’s best to hand over your wallet or bike.

Don’t give papaya!

‘No da papaya’ is a local way of saying ‘don’t make yourself a target’. And if you are a target, get out of it alive. Here’s some tips I’ve picked up from living in Bogotá for 12 years.

- Treat your barrio like a village. Shop on the corner, get to know the local characters, hear the gossip. If you are living in a block of flats, join the residents’ Whatsapp group (more local info).

- Know the crime hot spots in your local area. Where I live there is a river (where a cyclist was murdered for his bike), and a main road (Avenida Caracas) where a few abandoned houses have become ollas, or a local drug hangouts. I plan my walking routes to avoid these areas.

- Know where local emergency services are, the local police CAI (Comandos de Atención Inmediata), nearest hospital with ‘UCI’ (intensive care unit, there are many around the city).

- Have contact numbers for your nearest consulate, and register with your embassy (if they provide that service)

- Always carry ‘flash cash’, like 100,000 pesos which can be handed over quickly if you are held up.

- Be nice to beggars. Share a bit of food, recycling materials or spare change, and in return they will look out for you, and let you know the story on the street.

- If you are mugged, if you can’t easily escape (unlikely) then never resist, even in a crowded area, don’t count on anyone helping you (they will after the event, but not during). Street robbers are often young, highly stressed and under gang pressure to ‘get results’. Shooting you dead might be a good career move for them, so don’t give them the incentive.

- Carry your phone even if you risk losing it to a robber. If you are mugged, they will expect you to have a phone. Not having one could put you in mortal danger. I carry a cheap one.

Read my post here on homeless people in Bogotá.

How to avoid drugging: see my separate post Burundanga: it’s bad and it’s back with safety advice. Drugging is resurging in Colombia, the US Embassy recently posted a warning, so take precautions. Here’s a list.

- Avoid sex tourist area (mostly in Medellin and Cartagena) and infamous bars where foreigners congregate to pick up women (ask other travellers and hotel staff for latest info in your area).

- Avoid ‘gringo parties’ and ‘gringo nights’, these are often magnets for druggers.

- Use dating apps with great caution and choose neutral public spaces for first encounters.

- Go out at night with a buddy or some friends to watch your back.

- Never accept food, drinks or cigarettes from strangers.

- Buy drinks you can open yourself (beers, mixer cans Keep your alcohol and drug consumption to the minimum to have fun). Always watch your drink.

- Carry cash rather than cards, but keep it hidden.

- If you do use cards, use one debit with low account balance, or pre-paid card.

- Avoid flashy watches or jewelry.

- Consider leaving your phone at home (like the old days).

- Take platform taxis (Uber, Cabify).

- On the street, be wary of people asking directions or trying to give you a leaflet. Politely decline (no gracias).

- Never accept food, drinks or cigarettes from strangers.

- Avoid overfriendly strangers, particularly those in pairs.

Travel on local transport: I use buses and Transmilenio regularly, see my Bogotá bus blog here. Carry small change for the buskers (often migrants) so you don’t have to get your wallet out. Avoid peak hours weekdays (6.30am to 8.30 am and 4pm – 8pm). In 2023 there has been a spate of armed robberies on night buses arriving or leaving Bogotá. Taking a daytime bus will reduce this risk.

Taxis: use taxi or platform apps and avoid taking cabs in the street.Organised gangs use taxis to kidnap and rob passengers (‘Paseo Millionario’), drug passengers (or transport people drugged in bars). Another scam is for the taxi to ‘break down’ and the passenger (you) gets out to push…the taxi motor miraculously starts, and the car drives off with all your luggage…

Police scams: many of these, with police (fake or real)asking for your documents (only carry photocopies), searching you for ‘fake money’ (they swap your real money for their fake money). Another scam is a motorbike near-misses you crossing a street, the driver falls down, limps a bit, demands ‘justice’. Policeman (friend of motorbike guy) quickly arrives to insist you pay a ‘cash compensation’. Many variations on these themes, in these cases demand to talk to Policia de Turismo and if possible demand consular assistance.

Mass protests: avoid mass protests, even if you agree with the cause. They are always infiltrated by criminals (usually paid by political interests) to disrupt, which often involves robbing peaceful protesters’ phones and cameras.

Political threats: political party offices can become targets for bombings during election times, this has happened several times over the years close to where I live in Teusaquillo, where many parties have their temporary or permanent bases. These are small bombs that blow out windows and usually planted to ‘send a message’ (and sometimes ‘false flag’ attacks). Avoid to live or stay close to possible targets, and avoid walking past them during tense time such as election.

Extortion: extortion and ‘protection rackets’ plague much of Colombia, with organised crime gangs charging ‘rents’ from any commercial activity and killing anyone who doesn’t comply, even with specialised police forces dedicated to extortion (GAULA, Grupos de Acción Unificada por la Libertad Personal). Many victims are fearful to denounce, so data is scarce, but Bogotá is thought to have much lower extortion rates than the rest of the country because gang structures are generally weaker in the capital city, and police more likely to act. Around 1,300 cases were reported in 2022, spread fairly evenly around the city. Unless you start a local (and visible) business, you are unlikely to face an extortion demand, though your family and friends could be affected.

Kidnapping: Bogotá reported 11 kidnappings in 2022, of these 3 were in Chapinero. This low number reflects some underreporting (ransoms paid and the crime never denounced) but also the fact that kidnapping is not a crime of choice for gangs these days, it attracts too much attention from some specialised police units (the GAULA). Many cases are within extended families (custody battles) or business related. The exception is ‘kidnapping’ related to drugging cases where the victims is detained while drugged, or the ´express kidnappings’ where taxi passengers are detained by armed gangs and forced to hand over cash. Since these are not cases where a ransom is demanded, these crimes are counted under personal robberies.

Bike robberies: almost 7,000 bike thefts were reported in Bogotá in 2022, around 20 a day, and third of these by armed attacked (guns or knives). Attackers often target very expensive sports bikes and also take bags, phones or wallets. Engativá, Suba y Chapinero are three districts with high cases.

These attacks can be violent and several cyclists have been murdered for their bikes in recent years: a bike crime wave followed the covid pandemic and a demand for stolen bikes for delivery riders.

Attacks often happen in the early morning and late at night, or in daytime in remote stretches of cycle routes and underpasses and bridges. Because of the risk, in some areas of the city, cyclists prefer to use busier main roads rather than dedicated ciclorutas.

To reduce the risk, unless you are a serious sports biker, best to use an old bike to move around the city (you can buy good second-hand bikes from reputable bike shops or on Facebook groups) and wear scruffy bike gear.

Site security: staying safe at home

I don’t have figures for home invasions, though these are not reported much in local media. More common are motorbike gangs attacking people on the entrance to their building or garage, or car-jacking as the car is parked, particlarly at night when the driver gets out to open the garage door.

Choosing where to stay and the level of security depends a lot on your budget. Large residential buildings in wealthy areas have electronic entrance (face recognition or fingerprints), guards monitoring CCTV and automotatic garage doors. Residential flats blocks in middle class areas often lack guards, but might have CCTV systems and panic alarms. Check these details if renting a flat or AirBnB, and also the street access – the local ambience, street lighting, nearby risks (shady parks, bridges or underpasses).

Also be aware that in cheap hotels, hostels, shared houses and AirBnBs anyone can have copies of keys to your room, and the owners/managers will rarely respond to thefts. A digital safe where you can store valuables when you are out is a minimum security requirement.

Key control – or lack of it – can also put you at risk of assault or sexual violence in your own flat or room, if in a shared space. Rent rooms with a strong bolt on the inside of the door (‘pasador‘), and insist one is installed if it’s lacking. Most flats and private rooms already have them fitted, you should be suspicious if they don’t. Some travellers carry portable door alarms, or a simple door wedge that can delay anyone trying to enter your room at night (maybe giving time to react and escape).

Likewise most flats close to the ground floor have bars on the windows, but check for fire or smoke alarms and escape routes. Usually it’s best to avoid 1st (ground) or 2nd floor flats in Bogotá, and 3rd floor and above are more secure.

if you are renting a flat, join the residents’ whatsapp group and play your part in keeping the building safe, ie close the building doors and gates securely and report incidents of suspicious activities.

Where to get safety advice

It’s important to get updated security advice as you travel through a country, or if you settle in Bogotá. Embassy advice pages and warning to travellers is a good start, though tend to overstate risks.

On-line travel guides forums, ie Trip Adviser Colombia forum, you can filter down to Bogotá topics.

- Facebook groups (ie Expats in Bogota, Expats in Colombia, there are many more.

- Local news media (in Spanish) and English-speaking sources such as podcast Colombia Calling and Colombia Reports.

Other websites with Bogotá safety advice include:

I’ve highlighted the importance of getting good travel advice in the sad story Killed in the Darien Gap about a tourist who took a wrong turn.

Getting to know the city

If you plan to spend some time in the city, or if you are a curious traveller, there are plenty of guided tours to get to know the city without taking risks. There are many options these days and your hotel/hostal can advised, or you can find on-line. Here’s a few examples:

- Bogotá Bike Tours; 5 hour trips around the city center with many stops and explanations about the city.

- Bogotá Graffiti Tour; walking tour closet o city center with visits to graffiti landmarks and social history of the city. Also see my post Street Art in Bogotá.

For visits to some of the ‘down south’ barrios check out :

- Breaking Borders tours around Barrio Egipto, a hillside community south of the city center.

- For trips to Ciudad Bolivar, see my post on the visit Day trip to Ciudad Bolivar here. Tours can be organised with Ruta de La Esperanza , a foundation run by former gang member Andretti. This tour requires a fascinating trip in the Transmicable, which runs from Transmilenio portal El Tunal.

If you are the victim of crime

- If you are still in danger or injured, you should immediately contact local authorities by dialing “123” from any Colombian telephone for police and emergency services.

- Life-saving emergency medical treatment is free, so don’t hesitate to call an ambulance or get to your local hospital with emergency services.

- In the case of a serious attack or injury, you should contact your embassy or consular services, they can pressure authorities to assist and investigate.

- The US Embassy manages a Victims of Crime in Colombia website with useful data and you can send crime reports (in English) to acsbogota@state.gov.

- For British nationals there is a phone number for urgent consular help: +57 601 326 8300, selecting the option for consular services.

- Denounce the crime in person at the local police station or CAI, but they will likely refer you to the Fiscalía, the local criminal investigation department.

- You can also make a presential report to the Fiscalía at their key centers (often called ´URIs´), the police should give you the nearest location.

- For less serious crimes (or insurance reports) you can make a denuncia virtual via the Fiscalia web-page.

Cases of sexual violence

Patients with any suspicion of suffering sexual attack (male or female) should – in theory – get Post Exposure Prophylaxis (‘PEP’) treatment which tests and cures (or prevents) sexually transmitted diseases and HIV-AIDS. Rape victims especially need this to happen fast (within 72 hours of the attack) as drugs can be given within this window to stop any HIV infection. The actual drugging victim may be too disorientated to insist on this, but if you are supporting a friend or family in hospital do ask the doctors.

Nowadays in Colombia, Post Exposure Prophylaxis should be given immediately and without question to sexual attack victims – and not dependent on any ´crime report´ – but don’t always count on every health center to do this (the larger hospitals in large cities are a better bet). Push for PEP, and if necessary, find a private clinic or doctor to get it done…

The US Embassy has a list of recommended clinics and hospitals for emergency attention.