Loco for lichens

by Steve Hide

A version of this article appeared in The City Paper in 2017

For similar posts see

– The Giant Sloth Slaughter

–Do you have an Altitude problem?

In the herbarium of Bogotá’s Universidad Distrital, lichenologist Dr Bibiana Moncada opens a red envelope to reveal a leafy lichen, the one that happens to incorporate her name, Sticta viviana.

‘This specimen is the holotype,’ she says, meaning that the delicate weave of lettuce-like fronds she in her hand is the first specimen of the species to be collected and identified. It is not the only new species she has found, in fact she has classified dozens, many within a short distance of Bogotá.

We both agree that one task of a lichen expert is inventing names for all the new ones, and one thrill is having one named after you, though with a modesty typical of this scientific community Dr Bibiana’s had her name proposed by her colleagues, just as in turn she has put her own mentors’ monikers for her own discoveries.

The Distrital’s herbarium hold’s 20,000 samples from hundreds of species, but it is the tray of red envelopes – the holotypes – that I watch wondering: ‘this is numero uno, the first one known to humankind’.

It was a similar awe that first drew Dr Bibiana into the world of lichens as a student in the 1990s at the Universidad Nacional: ‘When I looked closely at lichens they were fascinating and beautiful, but also so unknown.’

Part of their mystery lies in the fact that while recognised as organisms and identified by species, lichens are actually a collaboration of fungi, algae and nitrogen-fixing bacteria, three classes of simple life forms that somehow somewhere decided ‘together we’re better’ and formed mini-ecosystems which, while looking superficially like mosses, are not plant life.

‘Lichens are fungi that learned to farm,’ explains Dr Bibiana. Fungi cannot photosynthesise so rely on sucking up nutrients, which kind of limits their scope of habitats (such as the debris of the forest floor). Algae are cells that can photosynthesize but lack the structure of plants, so mostly float about in water.

But put them together and hey presto you have a fungus that can feed on the goodness produced by the photosynthesizing algae – its own embedded snack pack – and an alga cell supported by the stronger fungi fibres that can literally get out of the pond. The cyano-bacteria get invited to the party for their ability to capture nitrogen from the air, a handy trick since nitrogen compounds are the building blocks of the fungi structure.

And what a structure. You have probably walk past a million lichens in your lifetime and never given them a second glance. But get close up and you will be amazed, like the first time you snorkel over a coral reef.

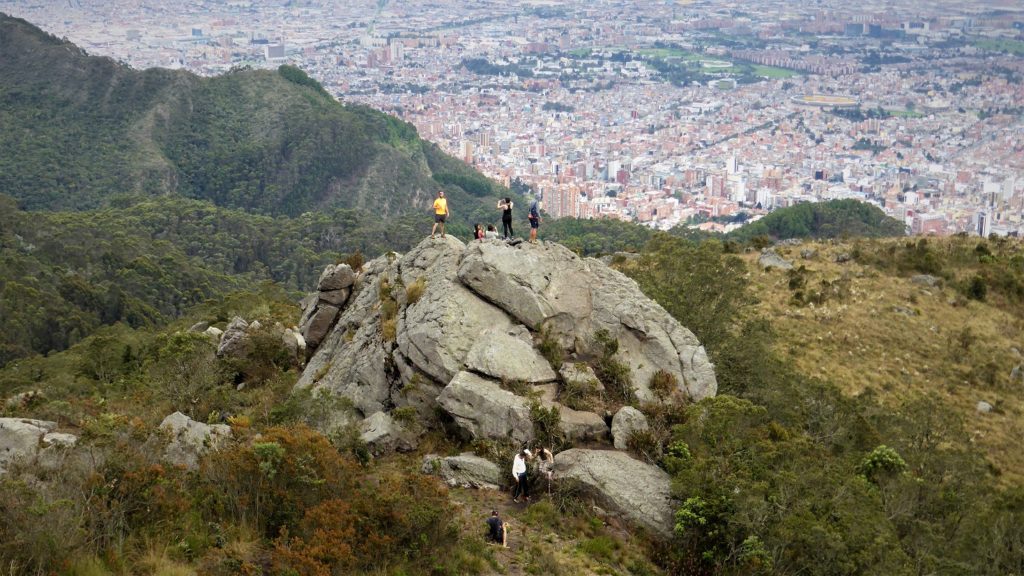

On a walk in the Cerros Orientales of Bogotá I take a magnifying glass and am soon enraptured by the myriad of colours and forms that lichens take from gun-metal grey lettuce-like leaves, to miniature forests of bulbous stalks, like little Shrek’s ears, to orange crusts coating rocks to the old-man’s-beard filaments coating the tree branches and making the woods magical.

It is a question that mentally pitches us into the primordial soup and, like cosmology, leaves us pondering life, the universe and everything. It also perhaps explains the almost religious passion that scientists share for lichens (a biologist friend in London throws his hands in the air and shouted ‘hallelujah’ when I casually mentioned the L word) and some of the extreme lengths taken to study them.

And all the time thinking: how did little critters ever first get together to make all this?

Such as sticking lichens on the outside of the International Space Station for 18 months to see how they get on in a pure vacuum with extreme heat and cold and ultraviolet and cosmic radiation. They not only survive but come back to earth and carry on growing.

Not surprisingly on tierra firma lichens have evolved to live in the cold arctic, hottest deserts and everywhere in between. Some individual specimens are over 10,000 years old.

Paradoxically, though, these extremophiles can also be highly sensitive to chemical pollution for example from car fumes which quickly stunts them or kills them outright.

‘Lichens lack the waxy coating that protects plant leaves, so any airborne pollutants are quickly absorbed by the chlorophyll at cellular level,’ explains Dr Bibiana. This means they make excellent bio-indicators to air contamination, a strand of research that her students have been doing in Bogota and Medellin to correlate lichen colonisation with traffic and air quality data.

You can use lichens to find the perfect home, she says: ‘When you decide where to live in a city, look for lichens,’ says the lichenologist. ‘The more there are, and the healthier they are, the better quality of life you will have.’

It is out of the city, though, that lichens thrive best and form an important part of ecosystems, colonising just about any natural surface, often living trees which they help by trapping water in their spongy bodies, and fixing nitrogen.

They are also a food source for animals and have been used throughout history by humans as clothes dyes and in traditional medicine where their natural antibiotic properties have been long recognised. The wispy Usnea lichens, for example, make excellent wound dressings.

Use of lichens by the indigenous people of Colombia has yet to be properly studied, says Dr Bibiana, though she is aware that until recently in parts of Boyacá lichens were used to dye ruanas.

Better understood is how the variation of lichen species can unravel long-term changes in the Colombian environment, such as the rising of the Andes over eons of tectonic change leaving biological islands of highland paramo with distinct species. This is Dr Bibiana’s speciality and one that drawn her team to the mountains around Bogotá, Guasca and Sumapaz, and to photograph and collect samples that form the collections in the Distrital and Nacional universities.

It is this work that is putting Colombia firmly on the world stage in terms of lichenology, and takes Dr Bibiana all over Latin America and to places such as New Zealand and Hawaii to study them. One of her finds, Lobariella sipmanii (which she named after an influential Dutch lichenologist) was featured in the UK’s Guardian newspaper for its ‘delicate beauty’ and how its discovery, and others similar, represents strides in collaboration across continents.

Whereas in times past taxonomy – the naming and classifying of species – was a lonely and tedious task undertaken by individual scholars, the trend now is for experts from across the world to work together and joint-publish scientific papers bringing new species to light.L. sipmanii was first described in a paper with 102 authors from 35 countries. Colombian lichenologists – there are around 20 – are firmly plugged into that worldwide network.

Classification of lichens used to rely on the physical characteristics and differences, often seen under a microscope (of which there are several in the Distrital lab) but nowadays the process is assisted by molecular DNA tests. But it still takes a good eye to spot an unusual and maybe new species, and a knack which Dr Bibiana has clearly acquired: just from re-examining existing samples in herbariums she found 40 new species of Sticta lichens, and 25 new types of Lobariella. Of the 18,000 lichens so far found worldwide, 5% are from Colombia and that number is sure to rise.

So far Colombian lichenologists have focused their studies on the Andes near to Bogotá, with good reason because the paramos are ‘evolutionary hotspots’, but also because they happen to be close to the universities where the Colombian Lichenologist Group is most active.

This leaves large swathes of Colombia relatively unstudied, though that is slowing changing with lichenologists looking at new zones such as the Choco, the Caribbean and Huila.

‘We estimate that there are 2,000 new species out there,’ says Dr Bibiana with a radiant smile. Somehow, I suspect Colombia’s lichen lovers will find more.

Find your own lichens

Resources: if you want to spot lichens in the Bogota hills there are some excellent photo field-guides made by Dr Bibiana Moncada and her team with the collaboration of the Field Museum in Chigaco. These can be downloaded for free at the for free here for free here .

Here you can use the search facility to find:

- Lichens of the Colombian Páramo – an overview of lichen commonly found above 3000 metres in the Andes around Bogotá.

- Líquenes de las cuencas de los ríos Fucha y Arzobispo, Bogotá D.C. – a more detailed look at specimens found along the rivers Fucha and Arzobisbo that run from the eastern hills into Bogotá.

- Líquenes epífitos de Quercus humboldtii – a remarkable collection of photos of the 50 species of lichens that live on just one Colombian tree, the roble.