Mavecure: hike the sacred mountain of the Orinoco.

In the remote east of Colombia, where vast jungles swathe the ancient landscapes of the Guaiana Shield, lie holy granite hills rising above steaming green foliage where intrepid travelers can now plant their feet on surely one the most remarkaple corners of the planet. I’ve put some travel details at the end.

Posted in October 2024. See related posts: Rafting the Guejar Canyon, Adventures in Gorgeous Guaviare, and Venezuela’s Incredible Orinoco River Delta.

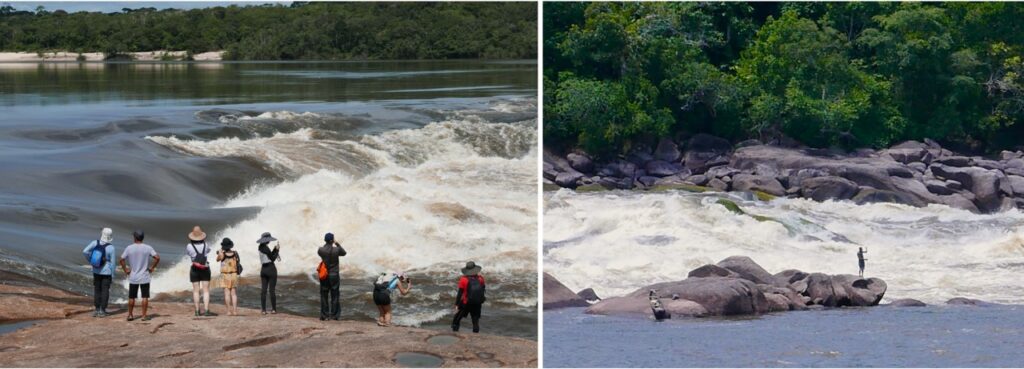

Mavecure is so amazing, I’m not sure where to start. Perhaps with the incredible geography of tea-stained rivers and sinking your feet into the ancient white sands of Gondwana. Or the charming local guides, from a panoply of indigenous tribes, teaching us how to fire a blow darts or leading us over dense jungle trails. Or the raudales, fierce river rapids that dwarf the fishermen below casting their lines into the eddies of the upper Orinoco where the grey-pink flanks of river dolphins gently break the swirl.

Ancient Landscapes of Guainía

So let’s start at the beginning, 1.5 billion years ago when the hot magma bubbled just below the Earth’s surface to crystalise into granite intrusions that, literally, stood the test of time as softer crust washed away leaving a series of steep domed hills dotted over flat jungles among vast rivers.

Climbing Mavecure’s stone ramparts to look out over these ancient landscapes has fast become Colombia’s most remarkable attractions, and with good reason: in my 45 years of travels, I can honestly say the five-day adventure tour in Guainía, the country’s easternmost department, takes top prize for excitement and value for money. There is never a dull moment.

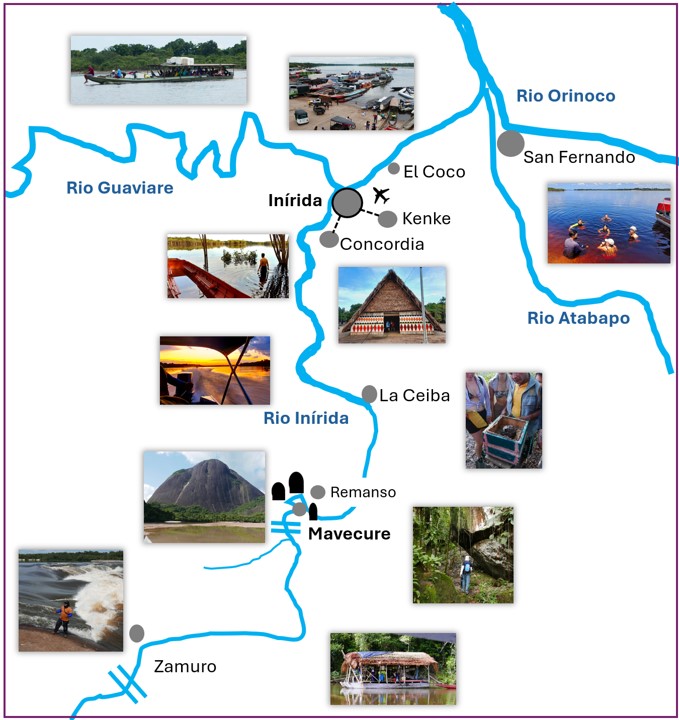

And it’s wild. Guainía has just 50,000 folk spread over 75,000 square kilometres, and less than 20kms of tarmac road, and that’s mostly to the airport. That’s a population like Braintree in Essex (or Waxahachie, Texas) in an area the size of Scotland. And most of those folk are in Inírida, the gold-rush town perched on the muddy confluence of the Rio Guaviare, one of Colombia’s largest rivers rising in the Andes close to Bogotá, and the Rio Inírida itself, a wild waterway descending over many rapids from the deep heart of the northern Amazon basin.

Uncontacted Tribes

Did I say Amazon? Yep, Guainía sits astride both the Orinoco, which flows into the Atlantic in Venezuela – see my post on Delta Amacuro – and the Rio Negro, a principal tributary of the Amazon. There’s a dirt track linking the two watersheds with a tractor and trailer taking passengers overnight to connect the two halves of the region.

This vast region is just begging to be explored but is generally off limits. Apart from the complicated jungle borders between Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela, there are a host of human dangers from the range of clandestine activities from smuggling, human trafficking to widespread illegal mining of gold and a range of rare earth metals such as cobalt and coltan bring riches to the region but also guerrillas, armed gangs and shoot-outs at Inírida’s corner bars where miners, middlemen and goodtime girls down whiskey paid for in gold dust.

And then there’s the uncontacted tribes still lurking in the deeper jungle.

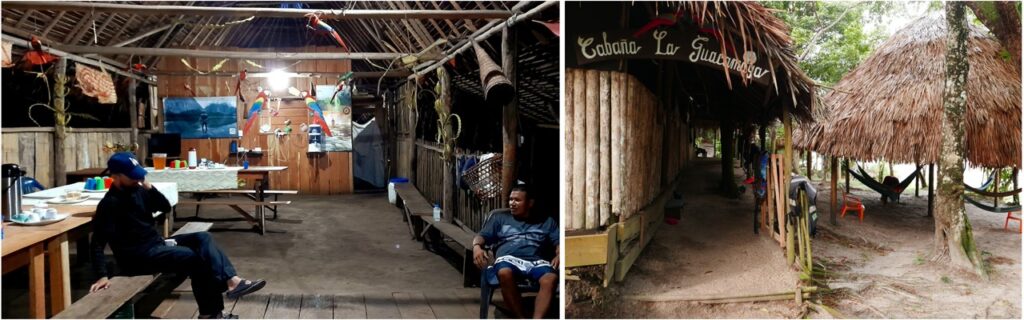

“We went six hours upriver to find some palm leaves for the roof, and met a tribe whose language no of us could understand,” explains Betty, the host of the small tourist settlement at Mavecure. This language barrier was remarkable considering that the Mavecure folk, like most assimilated communities in Guainía, are a mix of many ethnic groups – Puinave, Curipacos, Sikuani, among others – and the palm leaves team would share diverse tongues. But not these wild forest folk.

“They were painted, and armed with bows and arrows, and made it clear they would kill us if we didn’t leave. We headed downriver.”

Into the Unkown

Encountering this unencountered indigenous group relatively close to Mavecure was mystifying for Betty. Guainía’s far-flung indigenous populations were converted to Christianity by Sophie Muller – a New York Times journalist turned missionary – in the 1940s. You can read her remarkable story here. Somehow since then communities like Curipaco have shifted their ancestral heritage with adaptation to the modern world.

“We don’t know where they’re from, or what they’re doing here”, said Betty. “But we decided to collect palm leaves somewhere else!”

Talking to Betty, and the various guides over the five days, from a variety of ethnic groups, I’m struck by how much is still unknown out here.

And also somehow interconnected. Like most intruders I see the vast jungle as inhospitable barrier marking the remotest triple frontier of South America, and the wild rivers and their rapids are the only watery byways in which to penetrate this hinterland, and only just.

But for young indigenous guide Dreyk, who walks us to a sunset over the Rio Inírida, the jungle is a nurturing garden with countless tracks through which the initiated can travel long distances to connect communities whose peoples and lives are so far beyond the Bogotá’s city streets that my mind boggles.

The international ‘borders’ of Brazil, Colombia and Venezuela – alien lines on a map where on the ground few white men have ever walked – are a laughing irrelevance to a people whose waypoints link ancient trails under a thick canopy long hidden from outsiders.

A Hidden Network

“I’ll walk 20 days to visit my family in Vaupes,” explains Dreyk, telling us how he stays in small villages along the way. Vaupes is the large even remoter Colombian department south of Guainía, and also intertwined with Brazil. Like many indigenous in the region, Dreyk comes from a rich interchange of ethnic groups from across the Amazon and Orinoco region, creating kinship ties across tribes which has played a key part in ending territorial violence that could see someone clubbed to death for fishing in the wrong spot.

It’s a theme I hear repeated time again over the five days: cultural mixing reinforced by marriage, sometimes guided by a complex system of totems, other times just two people falling in love, has opened networks largely invisible to outsiders.

Of course, I only have their word for it: I’m only visiting their domain for five days. But my mind has been opened. And the possibilities seem endless.

“Dreyk, I want to walk to Vaupes! I don’t care how long it takes. When can we go?,” I beg.

He laughs. “Your body wouldn’t take it. The heat, the bugs, the long walks.”

Later, Betty gives me another good reason not to go too off grid: the armed groups, mostly remnants of Colombia’s guerrillas, won’t take kindly to wanderers. Even on the Rio Inírida close to Mavecure I see clandestine gold dredges, and several locals make it clear to me that this is still an area controlled by ‘alternative forces’.

A Flexible Plan…

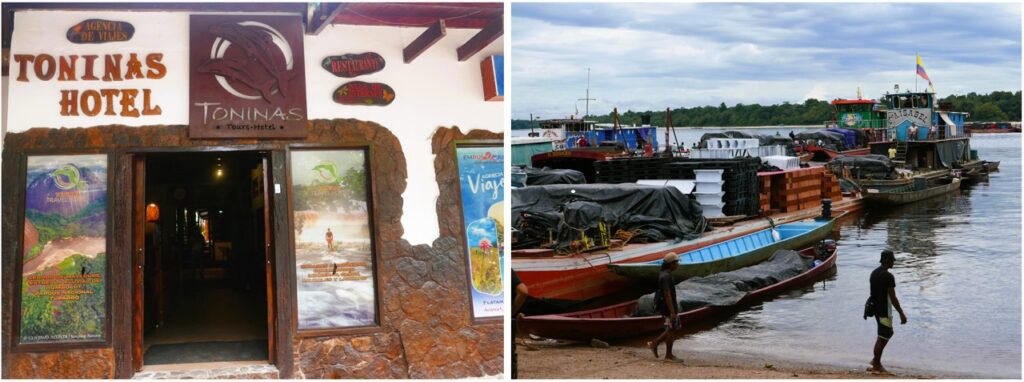

On the tourist trail, though, we are very welcome. A quaint hotel in Inírida, Hotel Las Toninas, has pioneered adventure tourism by stitching together various grass-roots experiences created by various indigenous communities keen to show off their cultures and scenery.

With a small fleet of fast boats, a network of lodges, hotels, guides and locals trained in tourism and food, and a variety of tour packages from three to eight days, Las Toninas has cornered the market, but to good effect. It all works brilliantly.

Don’t expect everything to go exactly as planned.

“You’re heading straight to Mavecure,” says Mauricio, the jovial owner of Las Toninas, as he greets at Inírada’s dilapidated airport. We were expecting to spend the first night in town and mellow with a visits to nearby communities. But what the hell, straight to the action.

Mavecure is two hours upriver, a thrilling voyage by fibreglass launch, with a thrumming 150 horse outboard, setting off from Inírida’s busy riverport. The river narrows and we pass small beaches of fine quartz sand, often the landing points for small villages. It’s October, and the last days of the wet season so the river is dropping until the heavy rains return next May.

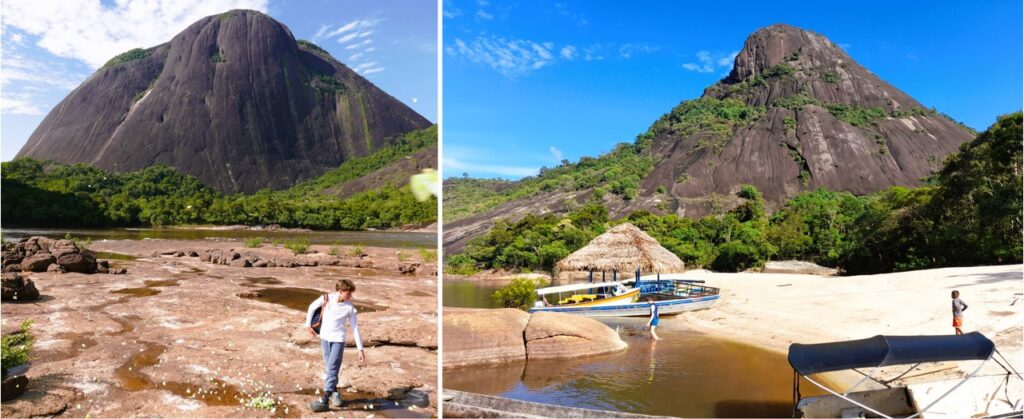

Then, in the distance, the looming triumvirate of grey monoliths above the plain, the first in view is Cerro El Pajarito, called ‘little bird’, though it’s anything but small, in fact a massive smooth lump of grey granite dome rising 750 metres above the plain. Behind it is the distinct Cerro Mono – monkey hill – and on the opposite riverbank the smaller but more rugged Cerro Mavecure itself, the one we will climb for the best view in Colombia.

Ascending the Sacred Hill

Next morning that’s exactly what we do, rising at four a.m. to grope our way out of our comfortable beds and mosquito nets to get in the launches for a short dash down the river to the trail head.

A string of torchlights bobbing up the darkened hill let us know another hiking group beat us there, but no matter, we get there with the grey dawn and group up for a pep talk with our guides.

“Use the rope and avoid where the rocks are wet,” is the main instruction. The steep granite flanks give good grip, but the long slope is unforgiving. Any fall would be fatal. Thick ropes are fixed over the steeper sections, and there are wooden ladders to scale vertical gullies on the upper sections.

But driven by adrenaline, and a desire to peak before sunrise, we are at the top within 90 minutes. Arriving at the rounded summit is heart-stopping; the hulking Pajarito and Mono to the north, a birds-eye view over jungles towards Brazil to the south, and the dark Inírida snaking its way under thunderclouds towards the Orinoco to the east. There are no guard rails and the grey convex hilltop tips alarmingly to sheer sides and precipitous drop to the jungle far below.

Then a local musician – known as the El Picaflor del Guainía – has chosen this time and place to record his latest video, so are treated to a musica llanera with its lilting harp accompaniment. But ragged rainclouds are coming in from the east, so we scurry down the granite slopes before the first heavy drops plop onto the foliage.

Back at the camp for a hearty breakfast, the storm breaks, but only for three hours. It’s the only rain we’ll get in five days.

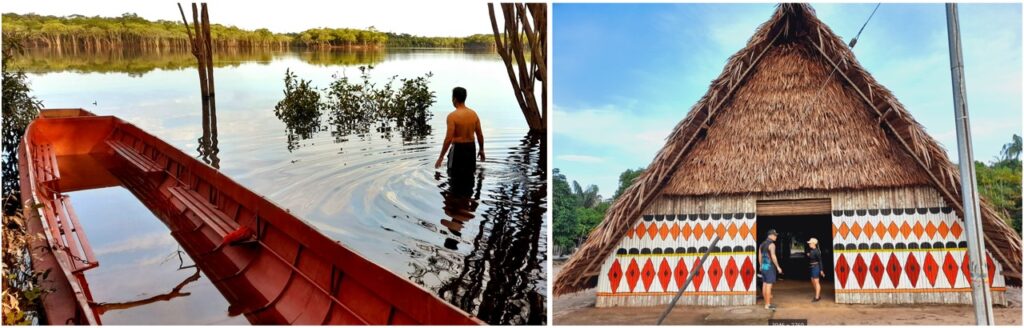

That afternoon we take another river trip with elegant aluminium speedboats, called voladores or ‘flyers’, to a nearby tributary where we can swim in the dark translucent water.

Dinosaur District…

It looks like tea, because basically it is: water deeply stained from the tannin released by jungle leaves dropping in the rivers. It all looks prehistoric; an orange river against white sand against green jungle with blue sky and grey stone hills behind. You expect a dinosaur to come lumbering out the bushes.

This is classic Guaina Shield, a geological zone covering eastern Colombia, most of Venezuela, the Guyanas, Surinam and a large chunk of northern Brazil. This worn, aged, region, sculpted from the time of the dawn of life on earth, still feels connected to an ancient supercontinent which spawned Africa and Australia. You could be in either.

There’s plenty more do in Mavecure. In late afternoon, when the shadows are falling, we trek for three hours until dusk around the back of Pajarito. The hike starts on the sandy tracks leading from the village of Remanso, but soon our guide is leading us into thick jungle. He is swinging his machete, occasionally whacking it against a tree trunk, and stomping hard in his rubber boots. The vibrations will send away any fer-de-lance vipers that sit perfectly camouflaged in the leaf litter.

Next morning, we are back in the boats again heading to another highlight of the tour: the Raudales de Zamuro, surging rapids. This is another two hours upriver, taking us deeper into Guainía, past some gold dredges where young fit men wave to us.

Catfish and Dolphins

Gold extraction here is illegal, but everyone has a hand in it – including our guide John who cheerfully admits to being a buceador – diver – whose unenviable job is to descend 10 metres to the gloomy riverbed for 4 hours at a time holding a massive suction hose to the suck sand deposits to the surface. These are then washed over a fabric coated frame where gold particles naturally sink and catch in the tapete, or carpet. The carpet is then cleaned to yield maybe ounces of gold, sold on through dodgy middlemen to infiltrate ‘clean’ gold markets and get certified into the world’s bank reserves. Everyone coins it so no-one really complains.

John’s main fear are the giant catfish that lurk on the riverbed and bite unsuspecting divers. I guess this is fair play given that several dugout canoes are fishing for the same beasts below the rapids.

We stop for a swim, and are briefly joined by toninas, the pink-grey river dolphins that are fishing the same eddies. The dolphins are shy, barely breaking the surface and keeping their distance, and are better swimming companions than a nibbly catfish.

That night we are back in Inírida, the main (and only) town, in the relative luxury of the Tonina’s Hotel. We’ve seen the dolphins on every river trip so far, so the tour company has earned its moniker.

Blow Dart Practice

There’s more to come: around Inírida we visit several indigenous communities, including a memorable lesson in poisonous blow darts. And for the finale, another long river trip, this time down the Rio Guaviare to the confluence of the Orinoco and Atabapo rivers in Venezuela. Here again is the remarkable meeting of the translucent orange waters rising in the Guiana Shield and the muddy river washing down from the Andes.

Our last morning, we wake at 5am, then walk from the hotel door to Concordia, a mixed community but mostly Cubeo, and from there on the Laguna de Las Brujas, a large lake lying in woodland next to the Rio Inírida.

We stroll in under an hour from the main town of Colombia’s fifth-largest department to a pristine wilderness. And back again in time to catch the 10 am flight to Bogotá. It’s a perfect end to a perfect tour.

PRACTICAL STUFF

- Book direct with Toninas travel, the four night – five-day Camino de Los Raudales is the best. You can find departure dates on the website. The 2024 cost was US$400, exceptionally good value. You’ll pay a lot more if you book through an external agency.

- Tours are designed to fit with the arrival and departure of the daily Satena flight from Bogotá to Inírida. These will need booking in advance, as flight fill fast. Return costs vary but start from US$200.

- Bring lightweight clothes with long trousers and shirts, swimwear, towel, hat, sunblock, mosquito repellent, waterproof bag, good boots with good grip, torch, raincoat, water bottle.

- The five-day trip includes two nights in Inírida (in hotel room) and two nights in Mavecure (in shared bunk house with mosquito nets). All food, snacks, clean water, coffee, and meals (mostly fish) and transport is included. Bring cash for tips, extra snacks and beers.

- October to April is the drier season, though it can rain any time of year.

- Expect some tough walks, three hours maximum, wear boots and long trousers for these because of bugs and stingy plants.

- The climb up Mavecure is challenging but even older folk managed it, there’s no rush. Bring gardening gloves to avoid rope burn.