Sailing historic Cartagena

What better way to feel Colombia’s colonial seafaring history than a week sailing its tropical coastline? A look at the where and how to get on the water from the country’s most attractive city.

See PRACTICAL STUFF at the end of the post for advice and tips for navigators.

Posted April, 2024

Cartagena de Indias is the gem of Colombia’s coastal cities, sweat-drenched in history, mostly of the seafaring type, with the stone ramparts of the walled city testament to tempestuous times of Spanish noblemen, English pirates, slaves and treasure in a salty seat of colonial power. You can still smell the gunpowder.

Sailing out of the inner harbour from La Manga is a voyage through time. Even as you leave the old city walls behind, the skyscrapers of Bocagrande, like a modern Miami, are a backdrop to yet more stone fortifications built by generations of slaves of the Spanish empire to fend off French and English invaders.

I’m on board of Rush Slowly, a Dufour 450 ocean-going yacht, part of a small crew cruising a small part of Colombia’s tricky coast with our grizzled Captain Mauricio, or simply ‘Capi’.

He guides us out of the inner harbour between two narrow spits of land guarded by the 17th century fortes of Fuerte Manzanillo, an impressive stone building today set on lush tropical gardens, and the ruins of the Castillogrande.

We cross into the cooler air of the huge Outer Harbour, a deep-water haven of over 40 square miles where you can raise the sails and run downwind on the NE trade winds that sweep across the hot headlands. Still, it’s relatively sheltered compared to the steep Atlantic waves you’ll hit once in the open ocean. Make the most of it.

El Draque: Terror of the Main

The larger bay is sheltered by Isla de Tierra Bomba, a large green island with yet more forts, whose northern point delimits the harbour’s wider entrance, Boca Grande, the ‘big mouth’. Into this gape sailed the English captain Francis Drake in 1586, thirsting for the rich cargoes of the Spanish Main, as mainland Latin America was called at this time, and challenge Spanish hegemony over the Spanish Lake, as the Caribbean was then known.

The sea and land battled raged for three days, before the English forces took the city and occupied it for one month, all the while looting its treasures and ransoming its citizens. Drake’s bold attack stunned the Spanish empire, and he achieved bogeyman status – mothers still scold their kids with “behave, or El Draque will come for you”.

Interestingly, Drake is also credited with mixing the first Caribbean cocktail, El Draque, of white rum, lime, mint leaves and sugar, a prequel to the Mojito.

After suffering several pirate attacks, Cartagena’s Spanish governors went big with their harbour defences, including an underwater seawall blocking Boca Grande to big ships, and two doughty forts – San Fernando and San Felipe – guarding the narrower Boca Chica (Small Mouth) entrance at the south end of Tierra Bomba.

“The Spanish armed the forts with special cannons that fired chains into the rigging to de-mast any attacking ships,” explains Capi, and later I find the same squat cannons now perched in the Plaza de Bolivar inside the colonial walled city.

The Spanish Lake

The two forts are well preserved and form a bottleneck for any ships leaving or entering Cartagena’s ample anchorage, and today proudly fly Colombian flags.

In the colonial era, the port was the Caribbean home to the pride of the Spanish fleet, the Flota del Tierra Firme, that brought both settlers and merchandise from Spain and returned laden with treasures from the conquered empires of Mexico, central and south America, attracting a rollcall of pirates and privateers, and a cast of colonial heroes who defended the walled city.

Since Colombus, the Spanish had seen the Caribbean as their own private sea, the Spanish Lake, based on a pillage economy that saw hordes of gold silver and gems forcibly extracted from the indigenous populations – often with great cruelty – and shipped to Spain’s royal coffers.

Dutch, French and English ship harried the Spanish fleets and raided their rich seaports, either as ‘privateers’ backed by letters of marque – in which case they had to deliver some of their own booty to their own crown backers – outright pirates and freebooters. The smarter sea-captains also broke the Spanish trade embargoes bringing much-needed European trade goods to desperate colonists under strict Spanish embargoes.

This included the evil trade of African slaves, in which all European powers were deeply involved, and England’s national heroes such as Sir Francis Drake and Sir Walter Raleigh.

The centuries-long struggle for control the Spanish Lake was fought out against a backdrop of torture, massacres, and atrocities against civilians partly driven by the religious intolerance of the day – Catholic Spain would burn captured English seaman as protestant heretics, and the privateers would in return send their Catholic captives to the seabed in chains.

But more often people simply drowned on ships, driven onto rocks or the seabed by fierce hurricanes, or wrecked during armed confrontations.

The Holy Grail of Treasure Ships: Galleon San José.

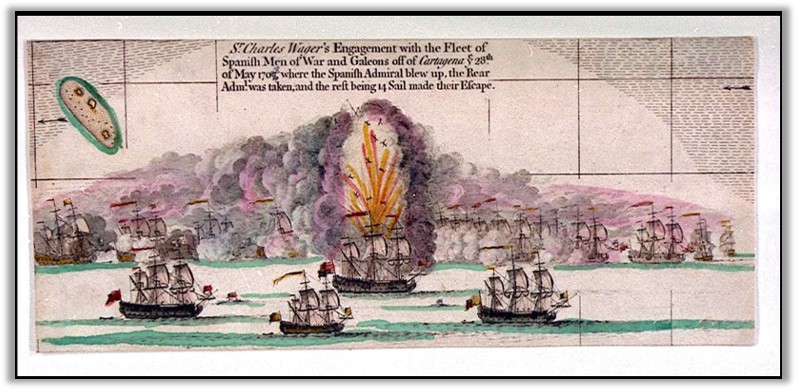

Close to Isla Tesoro, ‘Treasure Island’, 8 kilometers southwest of Tierra Bomba, lies the ‘Holy Grail’ of Spanish treasure ships, the Galleon San José, sunk fully laden with 600 lives lost after an attack by four British warships in 1708, in the Battle of Barú, known to the English as ‘Wager’s Action’, fought out against the backdrop of the Spanish War of Succession that pitched France and Spain against England, Holland and the Austrian Hapsburg monarchy.

The Spanish lost around 400 treasure ships during the colonial period, with a fair few around the Colombian coast, and many amateur treasure hunters, which explains why many wealthy landowners around Cartegena have clandestinely acquired colonial canons to decorate their driveways. At 600 meters deep (2,000 feet) the San José is beyond most huaqueros.

See my post here for the full story of the San José and the convoluted modern-day attempts to recover its estimated US$ 20 billion treasure of gold, silver and emeralds.

In 2023, Colombia vowed to recover riches from the wreck using modern submarine technology and, sailing out of Cartagena, we tail the ARC Caribe, a state-of-the-art research vessel operated by the Colombian Navy.

La Heroica

Strangely, the Caribbean’s bloody history is also punctuated by amazing acts of compassion. Drake, for example, could be a psychopathic punisher of the colonies, but at times charming and forgiving towards his sworn Spanish enemies.

And ironically, perhaps, the worst atrocity against Cartagena was committed by the Spanish themselves during Colombia’s independence struggle; royalist forces re-took the city in 1815 four year after it declared independence from Spain in 1811. After bombarding the city, and a months-long siege, thousands of the city folk died of hunger, and in the executions that followed. For its resistance to colonial powers the city is ever since known as La Heroica.

A good primer for this rich history – and a great to book to read before strolling the battlements of Cartagena – is the historical novel ‘Caribbean’ by James Michener .

Out to Sea

Heading out beyond the forts, we keep close to the edge of the shipping channel to avoid the huge container ships lumbering over the blue horizon. This is IALA-B buoyage, so the green cans are to starboard as you depart.

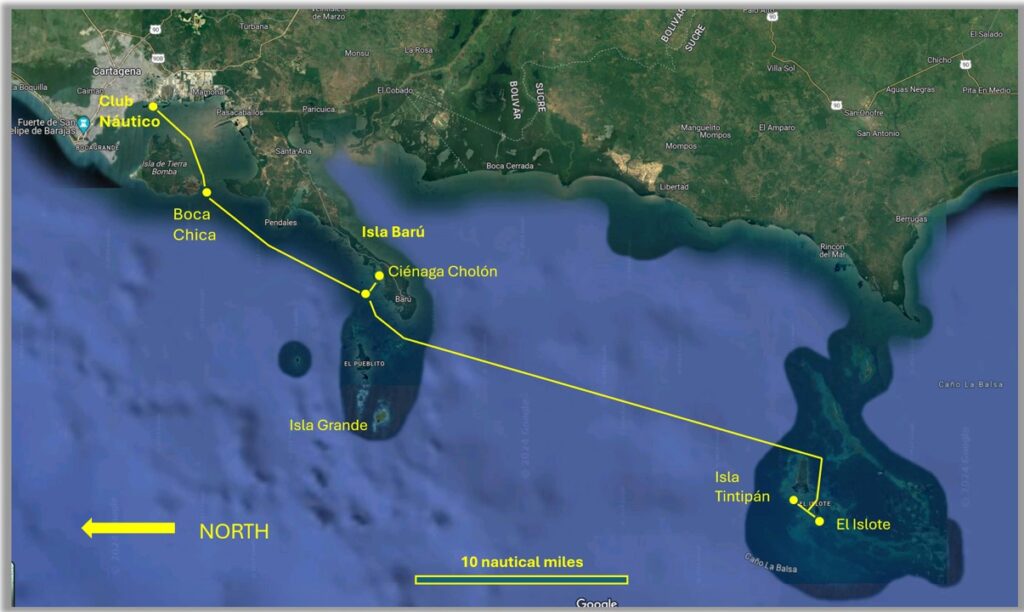

Once well past the forts, we leave the shipping channel behind and set course southwest along the peninsula of Isla Barú, a rocky coastline dotted with white sand beaches with green scrubby hills and few tourist resorts.

Now we feel the ocean’s full strength as the lively yacht rides two-meter waves driven by the trades. This NE wind blows constantly across the Atlantic, only slightly modified by the Caribbean islands in its path and blows at full strength along South America’s north coast before bending south around Colombia’s headlands.

According to The Concise Guide to Caribbean Weather by David (Davey?) Jones, the coastline regularly sees 35 knot winds and 5-meter (15 foot) swells. To complicate matters, the shift around Colombia’s curves condenses these waves into the steepest troughs, or “the washing machine” as Capi calls it, as our fibreglass yacht crashes and shakes on every foaming crest. For reason, world cruising guides rate crossing the southern Caribbean as ‘one of the top five toughest passages’ in any circumnavigation.

S.N.A.F.U.

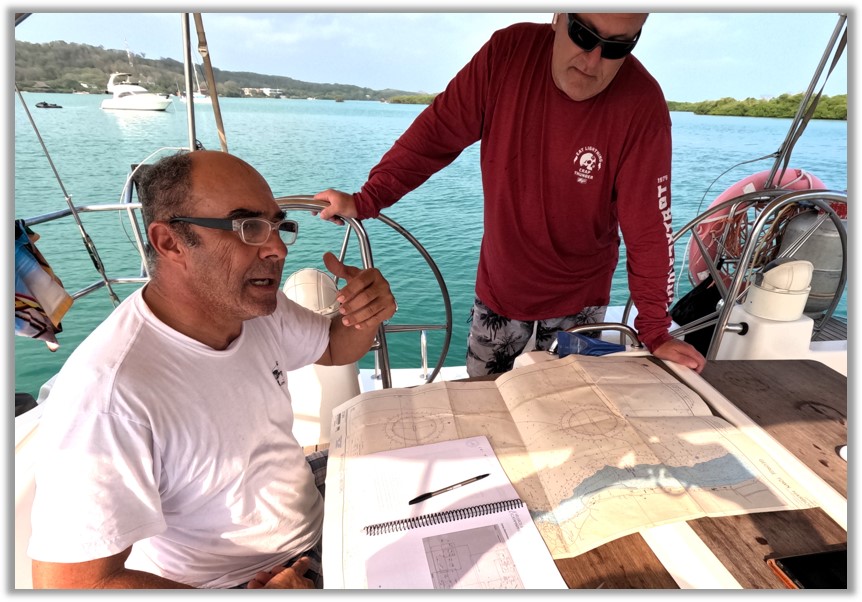

Rush Slowly is now running down a coral coast before 25 knots of wind with a rising sea. Our mainsail has two reefs, and the jib set to 50%, and our Capi is looking quite worried while fiddling with his cell phone. “My Navionics subscription has expired,” he laments, referring to the cell-phone app used by many sailors to guide their boats. The app keeps rejecting his credit card payments.

“We can use the plotter.” I suggest, referring to the inboard (and primary) electronic navigation tool carried by all modern boats. Cell phones are usually just a back-up. “The plotter was hit by lightning, waiting for repair,” replies Capi, still fiddling with his phone.

This is bad news. But there is more to come: the yacht’s VHF radio is never turned on (also kaput I suspect) and depth sounder on the blink. The last is particularly worrying, since knowing the water under your keel is especially important among coral reefs.

None of this surprises me in Colombia, a country where corners are cut and SNAFU (Situation Normal, All F****d Up) could be the national motto.

I try and see the bright side: “Oh well, nothing like a good old bit of traditional paper chart navigation,” I tell myself.

F.U.B.A.R.

Then we discover that Rush Slowly carries no local paper charts or pilot books and seems to be missing basic navigation tools such as parallel rulers.

Then, in an extra twist, it seems all the coastal buoys, channel markers and lights around the islands and reefs have disappeared …taken away by the marine authorities for “maintenance” some years back…and never replaced.

“There is talk of them coming back next year,” says Capi, but he doesn’t sound convinced. Our SNAFU is now risks becoming a FUBAR (F*****d Up Beyond All Repair). How could such a boat even put to sea? Particularly a training yacht with several newbie sailors ready to learn the ropes.

Even so, as we head out into the darkening ocean, I feel a perverse thrill: this is how Colombus and Drake did it. No charts, no apps, no plotter, no clocks. Just a bunch of sea sense. Though of course dozens of their ships sunk and thousands of sailor drowned.

Samsung to the Rescue

On the positive side, we do have a life-raft and Capi’s own Spot X emergency beacon as a last resort. And, of course, the Capi himself; a skipper-for-hire and freelance instructor and veteran of decades of Caribbean sailing, in every imaginable type of boat, from Trinidad to Panama to Mexico to Fort Lauderdale and every stop in between.

Then, miraculously, even out at sea there is 4G reception from the coast, and I can download Navionics on my own old phone, and, even more miraculously, when I tap to subscribe to the Caribbean charts – US$50 a year – the payment goes through. The next seven days the little Samsung will be our guide.

Cholón: Fun in the Sun

OK, to be clear, our week-long adventure down the coast of Colombia is more J K Jerome than Josh Slocum,and much of our sea miles are in sheltered bays where we can literally learn the ropes.

But as a training trip and ‘introduction to sailing’, including a thrilling night-time departure from Cartagena, in some high seas, it has enough adrenaline to keep us on our toes.

Our main anchorage and training ground is the beautiful Cienaga de Cholón, a half-moon bay protected by a ring of islets which break the Atlantic waves but allow in enough trade winds to sail some tight circuits.

It’s also the playground of dozens of tour boats and luxury motor cruisers that pound down the coastline from Cartagena brimming with rum, beer, bikinied chicas, and huge speakers pumping out reggaeton. After their pachanga most head back up the coast for sunset, leaving Cholón to the tranquillity of a few anchored yachts and swooping frigate birds.

A few islets dotted around the bay make perfect rounding marks for our practice course, with us heaving on ropes while Capi puffs on his e-cigarette and occasionally looks up from his book, squints at the rushing green water, and barks some salty command: “head her up now or we’ll end up in the mangroves”.

I’ve sailed before, and know my way around yachts, but want to learn some Spanish sailing lingo and see how they do it in Colombia. As forementioned there’s the relaxed attitude towards safety; even at night in a high seas no-one suggests donning one of the basic lifejackets stuffed in a locker somewhere.

The other surprise is a strong local tradition dictates that everyone is always barefoot on the boat. Which is fine until you dash to the foredeck to grab a flogging sail and smash your toes into the genoa track.

Sizing Up

Hanging out in Cholón is limited by the fact that Rush Slowy has no small boat or tender, not even a paddle board. And since we are at anchor for six nights, the only way off is swimming.

Not that it matters too much, given we have a ringside seat of the coming-and-goings of the luxury motorboats bringing mostly young females in bikinis – yelling and hollering – and shady-looking older guys.

“They’re just screwing, snorting and sleeping,” mutters Capi, at a large silver boat that’s strangely quiet and parked for three days by the mangroves.

The pretty bay is also ringed by boutique hotels, with some hide-away mansions built further up the scrubby hills. One seems outlandishly larger than the rest, almost made for giants.

“Built by a gringo living in the U.S.A,” explains Capi. “He sent the plans and some money to the builders here in Colombia, but it took ages to build, and the builders kept asking for more money, and more time.”

In fact, three times as long and three times as much money.

“When the America eventually showed up to inspect his dream house, he found out it was three times bigger than expected.” The building plan measurements were in feet, but in Colombian units are metric. The builders used meters instead of feet, producing a scaled-up mansion fit for giants!

Going Down the Tubes…

On day 3 of our trip, a ripple of gossip passes between the yachts anchored in Cholón: just outside the bay in the rougher ocean, a 40-foot luxury motorboat returning from the Islas Rosarios – part of the larger reef joined to Isla Barú – has sunk with 12 U.S. tourists and 2 crew were on board.

The boat was taking on water even as it left the islands, reports our deckhand, who is closely tied to the local boaters and constantly on his phone.

“Rumour is it had a broken tube. It filled up and sank very fast. The passengers and crew were rescued by other tour boats.” News reports later state the company hiring the boat lacked a proper licence, which the owners strongly deny. Too late for the boat though.

Capi and the deckhand then reel off the number to luxury yachts that have sunk from the “broken tube” problem, including a stunning historic wooden schooner and other multi-million-dollar vessels some of which have sunk at anchor in the yacht marina.

“The tubes are old and crystalise, then fail and the boat sinks,” explains Capi.

For the non-nautical, the “tubes” are part of the boat’s plumbing that attach to the through-hull fittings needed to allow water in (for engine cooling, for example) or out (the toilet flush). With good reason, most sailors fret over these holes through the hull, and ensure to fit the strongest valves (called ‘seacocks’) to lock them shut when not needed.

South to the San Bernardo Islands

After a bronco ride back to Cartagena – bucking the wind and waves – we do a quick turnaround in the Club Nautico, La Manga (the port’s main yacht harbour and where most foreign boats anchor off) and set off again at night for Cholón and the coral islands of San Bernado archipelago.

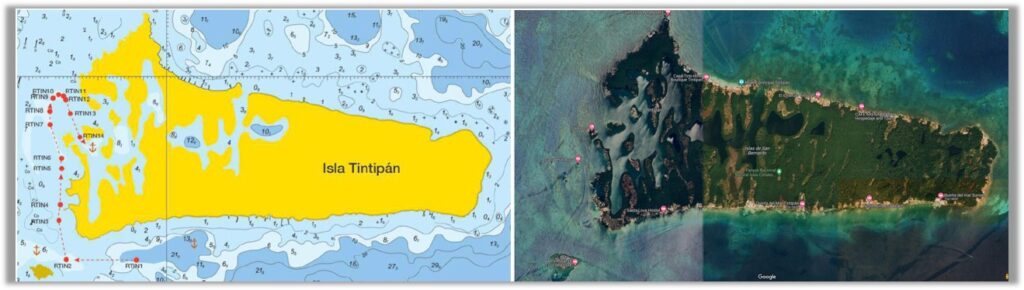

Leaving Cartagena at sunset, Capi helps us read the blinking green lights that mark the main channel. Then, in the open sea, we need the moonlight to steer down the large swells without broaching the yacht. Next day we reach Tintipán, a small island barely above water, a narrow green strip of land dotted with mangrove inlets and home to a string of Instagramable lodges perched directly on the reef, including the ‘eco water hostel’ the Casa en el Agua.

World’s Most Crowded Island

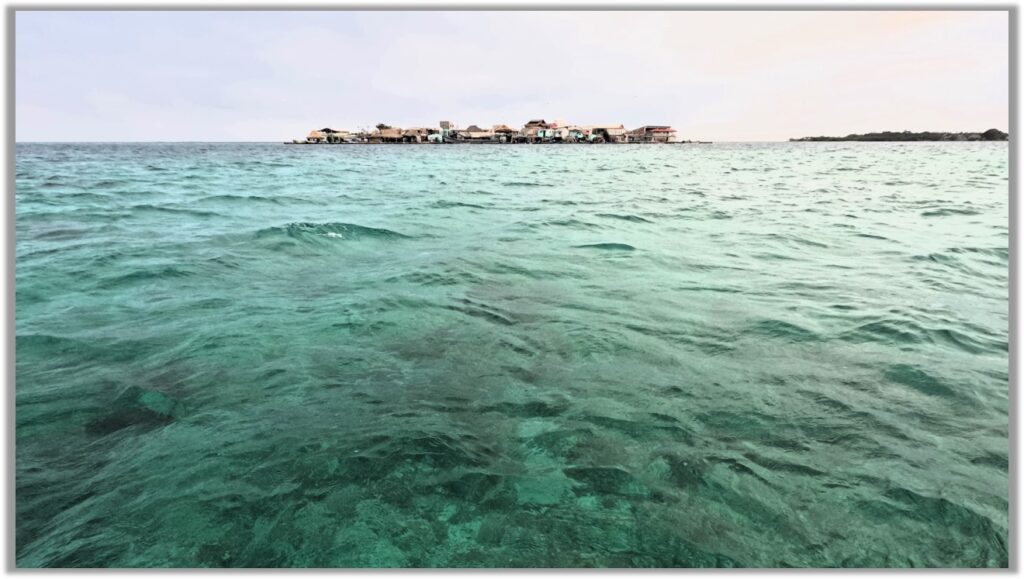

Half a nautical mile from Tintipán is the remarkable island Santa Cruz del Islote, usually simply referred to as ‘El Islote’, which is 1 hectare big (around 1/100th of a square kilometre) with around 850 inhabitants, claiming to be one of the most densely populated place on the planet.

The ocean here is full of life, we see dolphins and a turtle, and the water much clearer than Barú.

The question is why do these fishing families live crammed onto El Islote instead of settling on the much larger Tintipán? I ask as we stroll through the narrow streets of the crammed islet. Capi has the answer: “Tintipán is plagued by flies and mosquitoes, which for some reason don’t live on El Islote.”

The small community seems well looked after with a health post and small school, and the sea’s bounty literally on the doorstep; the wharf has some sea-washed fish pen with crabs, crayfish and some huge groupers waiting for the table.

Back on Rush Slowly we edge around the southwest corner of Tintipán and into the labyrinth of finger-like mangrove bays, where we anchor in a small cove with deep dark water where jellyfish pulse by, though the water is clear enough for us to spot them and swim clear.

The mangroves ringing the cove are home to oysters, bright orange sponges and a host of soft coral. Darting between the sun-dappled roots are schools of reef fish and baby barracudas.

Back in Cholón, we have more time to practice our knots and Spanish nautical lingo (see this useful list here):the good news is it is just as confusing as the English. For example, the rope to pull in sails is a “sheet” in English, and equally madly a “cabo” (cape or headland) in Spanish. We do more circuits around Cholón with some Man Overboard drills.

Death of a Swedish Sailor

That night, at anchor in Cholón and chewing on crayfish tails washed down with cold beer, talk turns to the mystery of Magnus Reslow, a sailor whose 30-foot yacht was washed up on the Colombian coast in February after the lone Swede left Santa Marta. A body was also found, but little data confirmed, hence the mystery as to how and why he died.

According to news sources, and some video interviews, Magnus was a plucky solo sailor navigating against all the odds in a very basic boat with a shoestring budget.

Clearly, he was a highly seasoned, with 30 years at sea, but he also embraced a nihilist philosophy, avoiding where possible modern navigation and using an old school atlas to chart his course. He gained worldwide attention in December 2023 after international news reports of he how he single-handedly fought off gangs of Colombian pirates who boarded his boat three times while passing the coast on his way to Panama.

The lurid descriptions of how the pirates attacked Magnus with sticks, even stabbed him, then stole everything off his yacht – even as he harried them with flare guns and grappled with them mano a mano – brought Magnus fame and some cash, via generous supporters and a Go-Fund-Me page.

History of Mishaps

The Santa Marta events seems follows a pattern in Magnus’s life at sea: mishaps in a broken boat with no engine, no electrics, poor navigation, drifting past his target port, needing rescue, followed by appeals for help and generous locals and seafaring community chipping in to get the lone sailor back to sea again.

A year before the pirate incident, in 2022, his boat Dhokus II was “found drifting off Aruba” after the Swedish sailor “requested assistance”. The disabled boat, with no working engine, was towed to port.

Back in 2015, Magnus had made headline after setting off from Sweden in an even smaller yacht with “no engine, no radio, no wind vane, and no navigational charts” before arriving a hero in the Canary Islands after “3 months lost at sea” during which he suffered 10-meter waves and several capsizes.

In another incident, in 2007, Magnus recounts an asthma attack where he “fell unconscious” before requesting rescue from Italian coastguards. His boat then capsized, ran aground, and was looted.

Pirates of Colombia?

Now in Colombia, the Swede’s pirate story, which ricocheted around the yachting world, was picked up by many cruising forums with many vowing “never to stop in Colombia”. Other yachties – while lamenting his demise – are sceptical that the solo Swede fought of three boatloads of ‘pirates’ who were, surprisingly for the region, unarmed.

While petty theft is common on yachts in Colombia, acts of piracy are rare. If we look at data from the Caribbean Safety and Security Net there have been five reports over 8 years, before Magnus’s ordeal:

- Taganga Bay, December 2023, an anchored yacht attacked and robbed of all valuables, crew pistol-whipped.

- Isla Tortugilla, May 2023, armed men assault an anchored yacht, ransack yacht, kidnap and interrogate crew (accuse them of drug smuggling) crew released unharmed.

- Isla Barú, March 2020, armed fishermen attack yacht and try to steal dinghy, injure crewman.

- Isla Barú, March 2017, armed men board yacht and steal safe and peanut butter.

- Taganga Bay, November 2015, five men with guns assault and rob valuables from yacht.

The common factors were that the yachts were anchored, attacked at night by armed men usually in paddled canoes, targeting small portable valuables, dinghies, and outboards. This points to opportunistic attacks by local criminals or fishermen, rather than organised ‘pirate gangs’. Magnus’s attack – in daylight, sailing at sea, and by unarmed pirates who at one point were “throwing glass bottles” – was clearly unusual.

Agreed, Colombia is a dangerous country with 13,500 homicides in 2023. But it’s probably worth to note that large criminal gangs in Colombia make vast profits from cocaine smuggling and would not make waves by attacking tourists in boats.

In other places, poor local fishermen would, on the other hand, be hungry for dinghies and motors and small stuff they could sell on. This correlates with the large number of thefts of dinghies and motors all over the Caribbean.

And Taganga, a sheltered bay, fishing village and seedy tourist hotspot close to Santa Marta, is notorious for its drugs, criminal gangs and wayward behaviour; the last place to recommend a yacht to anchor.

Out to Sea and Out of Luck

In February 2024, Magnus Reslow ran out of luck. According to an analysis by sailing journalist Jens Brambusch, who interviewed Magnus after the pirate attack, the Swede left Santa Marta alone on the 14th February with no working motor or self-steering, and was woefully prepared for the high seas and 30-knot winds along the coast. He left port without the proper sailing permit,the zarpe, after failing to pay his clearing agent there.

The wrecked yacht and sailor’s body were found 5 days later washed up on a beach close to Puerto Velero, 70 nautical miles downwind and down current from Santa Marta.

Before setting sail the Swede told the marina he was heading east to Taganga Bay, but instead sailed due north from Santa Marta, trying to get well offshore before running downwind on bearing line SW to Panama, with ample clearance of the dangerous currents around the Barranquilla headland.

Maybe not far enough offshore. By his own words, Magnus would often rest at sea by dropping sail and letting the boat drift. Such a strategy would be fatal while around the Barranquilla coast with the multiple jeopardy of high seas, fierce currents, a lee shore, and the outflow of the mighty Magdalena River which discharges tree trunks into the turbid ocean.

Perhaps the yacht was swept into danger while the tired sailor slept.

Still, the question lingers: was the Swede targeted again by criminals when he left Santa Marta the second time? In Colombia, you can never count out violent acts. But so far, the facts point to a simple shipwreck.

Magnus’s experience is a reminder of the dangers – human and natural – when sailing close to Tierra Firme of South America.

Back to La Heroica

Our last sail, back to Cartagena and the Club Nautico marina in La Manga, is a close haul against punchy waves back up the Barú peninsula.

After seven days up and down this coast, the waymarks are familiar; Punto Gigante, a rocky headland with nasty overfalls, Playa Blanca, the tourist beach I visited often in my younger days, and the two forts – San Fernando and San José – guarding the narrow Bocachica entrance to the outer harbour.

Following the green buoys through the outer, the channel is blocked by a huge cargo ship, turned sideways to wait its turn to manoeuvre into the dock. We skirt around its stern and duck into the inner harbour by Manzanillo Fort.

Then past the yachts anchored off La Manga; a motley fleet of battered cruising boats tending their wounds after an Atlantic crossing and tough sail through the ABCs (Aruba, Bonaire, Curaçao) before setting off again for Panama, the canal, and maybe the Pacific. Other boats have island-hopped down the Lesser Antilles from Puerto Rico, with each new port of call a testimony to the mad-scrabble conflicts of the Caribbean; a few hour’s sail will bring your from English, Spanish, French to Dutch-speaking islands, and back again. Many smaller islands are still ‘territories’ of their European colonizers.

Looking at these ocean-weary yachts, I realise my week with Rush Slowly has just covered a minute fraction of the Caribbean. Still, I ‘ve dipped my toes in the Spanish Lake and will surely come back for more.

PRACTICAL STUFF

Cartagena City

Cartagena is a year-round destination, but avoid the busy and booked out in December – January and the week before Easter (Semana Santa in Colombia). The old walled city –has plenty of boutique hotels, but you pay a premium for this zone. Boca Grande, with its skyscrapers, is more modern luxury. Cheaper accommodation can be found in Getsemani, La Manga, Crespo zones.

The plazas, churches, colonial architecture, and museums of the Old Walled City form part of a UNESCO heritage site. A good plan is to visit museums in the morning and afternoon (most close at 6pm) then walk the historic battlement walls at night. Museo de Oro Zenú, Museo Naval del Caribe, along with Museo Histórico de Cartagena de Indias, in the old Inquisition Palace in Plaza Bolívar. Ensure to visit the wonderful Castillo San Felipe, 17th century fort.

Also to leave time to just wander the streets, which come alive after dark and are safe to walk if you stick to the well-lit areas.

Safety and Security

The city is a major tourist destination for both Colombian and foreign tourists (and an overload of Cruise Liners) and locals are well adept at fleecing visitors.

My advice is:

- Avoid the city beaches, there are much better places to swim outside the city.

- Don’t walk after dark outside the Walled City, and even there take care.

- Never carry unnecessary valuables. Keep cell phone well hidden.

- If using taxis, get to know the city pricing zones, there is an QR code at the airport or check this recent blog from Cartagena Explorer.

- Avoid buying from street vendors, even food and snacks, it’s always a hassle, and might by bad quality food. Never buy drinks on the beach, you will be overcharged. There are plenty of small shops selling beers etc.

- Most traveller complaints stem from price-gouging and aggression related to over or ‘extra’ payments from local businesses; for this reason organised tours or ‘all inclusive’ deals organised by the hotel etc might be good option, especially if your Spanish doesn’t extend to “vete a la mierda, hijeputa estafador”.

Boat Trips to the Islands

There is a wide variety of boating day trips to the nearby islands, using speedboats, sailing boats (catamarans), larger slow ferries and overnight stays on islands. Speed boat tours start from the Muelle La Bodeguita, a short walk from the Torre del Reloj (clock tower). and often include stops at islands and beaches, snorkelling, lunch and drinks for around US$70 or less.

Cheaper tours just visit popular beaches on Isla Barú, such as Playa Blanca. Pricier tours take in the Islas Rosario. Slower budget travellers can also explore Isla Barú by road, with local taxis or motos, and stay in the village of Barú at the tip of the peninsula.

For more remote islands, and clearer water for snorkelling, visit to the more remote Islas San Bernado require an overnight stay, there are lodges in Tintipán and Múcura island, and the famous Casa en el Agua perched on the reef, which has a daily speed boat run to Cartagena (2 to 3 hours). The fascinating community of El Islote has its own Hostel Santa Cruz del Islote, for an unusual cultural experience.

Note that the San Bernado archipelago is more easily visited by boat from the small town of Tolú, a three-hour bus ride south from Cartagena. Close to Tolú are the lovely beaches of Rincón del Mar, and Punto Seco, with many lodges and restaurants, for a taste of the coast without going to sea.

If you taking speedboats, the seas can be rough, particularly on the return leg, and passengers have suffered injuries from the bouncing boat; if you have a fragile back then take a bigger or slower boat (catamaran) or sit at the back of any speedboat.

You can hire a private speedboat or luxury yacht from US$500 a day to US$20,000.

Cartagena is the base for yacht trips to Panama’s beautiful San Blas Islands with many larger charter yachts selling the week-long package trip to backpackers wanting an alternative way to travel between Colombia and Panama (or vice versa). Check out Blue Sailing for more details.

Yacht bums with sailing experience can catch rides on yachts eitherm free, as paid crew (depending on experience and qualifications) or as paying passengers fro short legs, starting in Cartagena or Santa Marta. Note that many yachts need extra crew to work the mooring lines while they pass through the Panama Canal. Webistes like FindaCrew and Crewbay can link staff to boats. Some yachts are seeking ‘yacht sitters’ to live on the craft in the marina for days or weeks.

My trip on Rush Slowly was part of a week’s Inshore Sailing Skipper course done by Veleros Colombia, you can find details on their website. Overall sail training costs in Colombia are much higher than UK or the US, but you will get a lower price for couples (shared cabins) and last-minute discounts.

Navigating the Coast

- For some positive reviews of cruising Colombian waters check out this Yachting World story.

- Colombia is south of the hurricane belt (June to November) except for Isla San Andrés and Providencia islands (owned by Colombia but off the Nicaraguan coast. Some info on the Hurricane Iota which struck Provicencia in 2020 on my blogsite here.

- For yachting safety and security updates check in with Caribbean Safety and Security Net.

- If you are an international cruiser arriving in Colombia, Noonsite has chapter on Colombia yacht clearance, and the zarpe, but as it states “laws in Colombia are ever changing”.

- The Navionics Caribbean Chart covers the Colombian coastline, though errors have been reported; keep a close lookout, watch the depth sounder, and use polarised sunglasses to detect the shallows and reefs. Savvy Navvy does not cover Colombia at present (April 2024).

- Note most of the navigation buoys marked on the chart were physically missing in April 2024, and no timeline for when they will be reinstalled.

- Some good general advice but dated (2001) from Caribbean Compass on Cruising the Coast of Colombia.

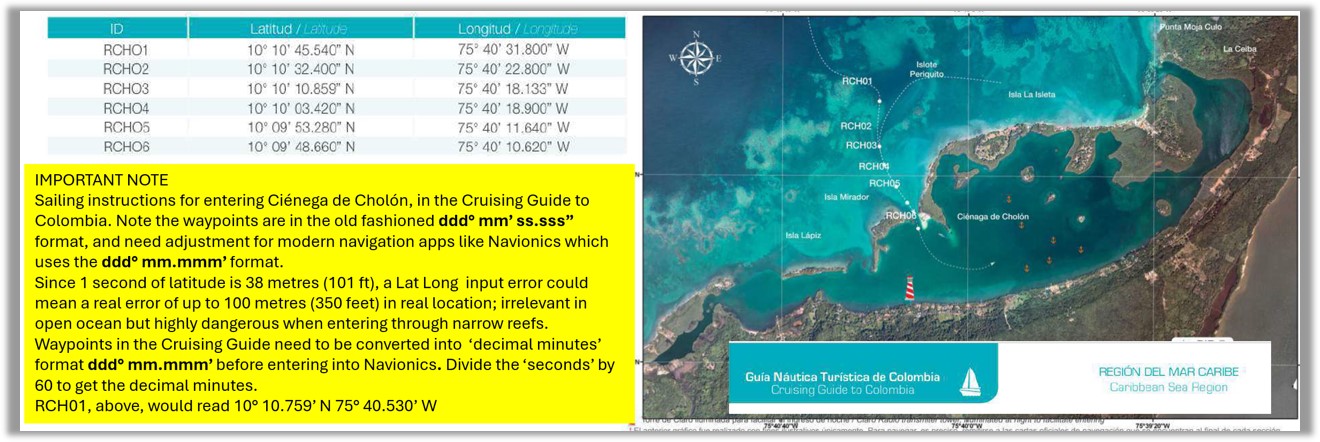

- More detailed sailing instructions and waypoints for tricky entrances from Sailing the Caribbean Coast of Colombia Part Two: Cartagena and the Southern Islands, by Constance Elson, from 2021, also on Caribbean Compass. You can download a longer pdf here.

- Officially, Colombian maritime navigation is managed by DIMAR , which published a very detailed (464 pages) bilingual Guía Náutica Turística de Colombia from 2017. You can find a free online PDF copy here unfortunately I have not found where to buy the physical book (which has many chart pages), there might still be copies in the marinas in Cartagena or Santa Marta.

- Note that the Guía Náutica Turística de Colombia uses dd mm ss (degrees minutes seconds) for its waypoint, while Navionics and most other navigation nowadays uses dd mm.mm format (degrees minutes decimal minutes). The difference is small but could create a location error of 100 meters or more, dangerous around reefs. Ensure to convert dd mm ss to decimal minutes if using the Guia waypoints. The Caribbean Compass docs mentioned above do use the dd mm.mm format.

Happy Sailing!