Sunken treasure: the Galleon San José

by Steve Hide

A versions of this article first appeared in The City Paper in 2017

Climbing up a vertical mineshaft with 60 kilos of tin and silver ore in a cloth bag on my back was the first and last time I laboured in a mine, albeit briefly, and then only as part of a tourist challenge in Cerro Rico, the Potosi silver mountain of Bolivia.

The game was to match the Bolivian teenage miners who scrabbled for precious metals in this crumbling centuries-old labyrinth of tunnels and caverns that once provided more than half of the silver in the Spanish empire, and whose very name conjures riches beyond count. For the Chinese of the day ‘Potosi’ was their word for Shangri-La, a fabled land of riches. Today in Spain peoples still say ‘vale un Potosí’; ‘it’s worth a mint´.

Of course none of us could beat the young miners in the ore-carrying contest. But the test stays sharp in my memory, along with the suffocating smell of ore dust and dynamite and the little carved niches lit by flickering candlelight where miners still worship a small statue of El Tío, a little devil who has looked over the generations of Quechua and African slaves worked literally to death is these hellish depths.

Spain’s colonial riches came at huge human costs. Some historians estimate that more than 8 million slaves died in the colonial process of mining, extracting and transporting the precious metals of Potosi, seen by many as a diabolical machine that consumed humans and belched out shiny ingots for the insatiable European superpower.

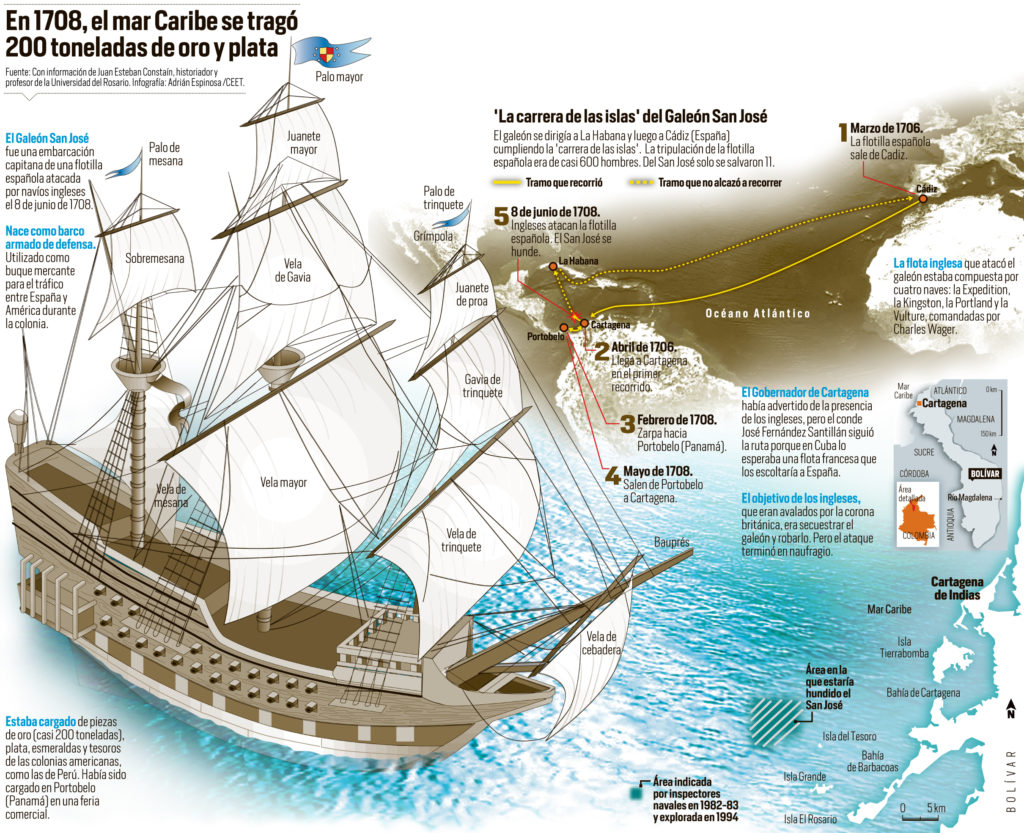

The silver bars and coins stamped with ´PTSI’ (which some say is the origin of the $ sign) would have been transported up the Pacific coast to Panama City, then carried on mule trains across the narrow Central America isthmus to the Atlantic port of Portobelo, to be loaded again on the mighty treasure fleets sailing for Spain.

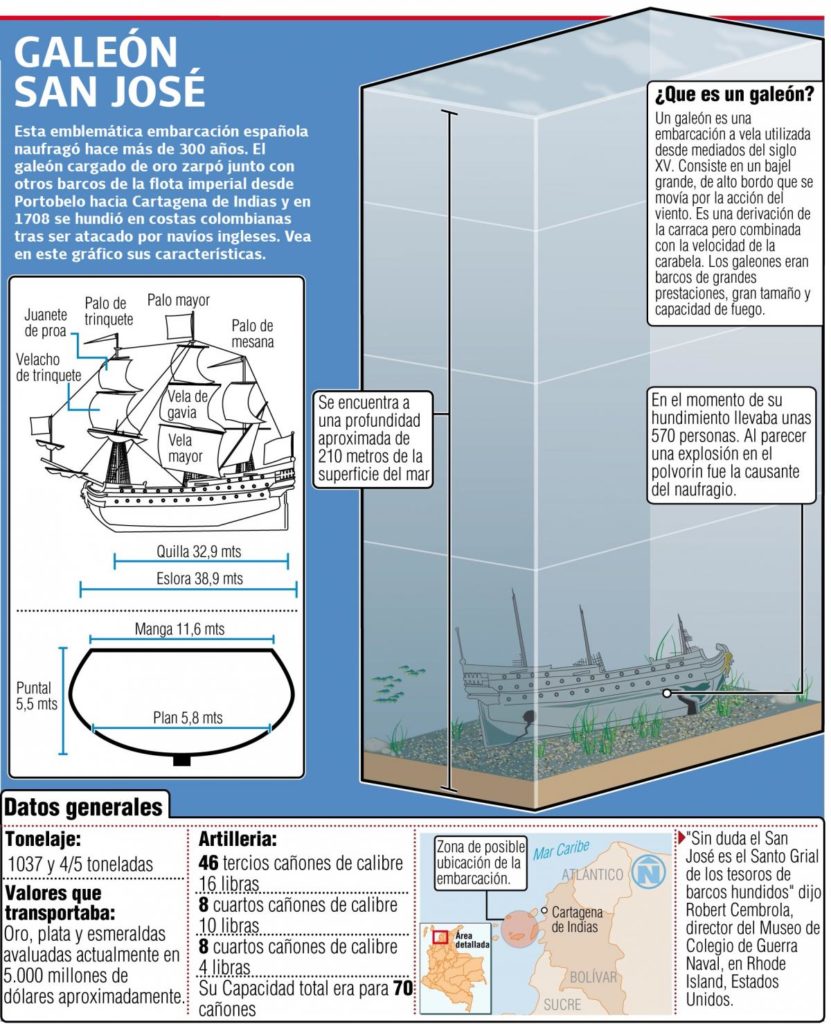

Some boats never made it, such as the Galeon San Jose, which was blown up and sunk by a British warship a few miles short of Cartagena’s fortified harbour in 1708. The sinking was a disaster for the Spanish crown eagerly awaiting its first treasure fleet in six years, but also a human tragedy as six hundred crew and passengers who drowned when the laden ship foundered ‘in less time than you can say a prayer’.

The precious cargo went to the seabed. But what exactly? No-one knows for sure. Some say colonial taxes of 11 million gold doubloons each weighing 8 grams. Other historians talk of nine million Reales de a Ocho ‘pieces of eight’, a 27-gram silver coin minted in Potosi. Others talk of 200 tonnes of gold and silver bars, pearls, emeralds and jewellery, much of it packed in the private chests that belonged to the 300 wealthy passengers.

Treasure hunters on the horizon

So over the years the San Jose has become a kind of underwater Potosi, legendary and far away, tainted by tragedy and fortune. Why, it even gets a mention in Love in the Time of Cholera along with Marquez’s own attempt at a cargo list: ‘300 chests of silver…110 chests of pearls, 110 chests of emeralds… and 30 million gold coins’.

And there the story might end. Except that in 1979 a US company Sea Search Armada agreed with the Colombian government to find and excavate coastal wrecks for a 50% ‘ownership’ of the ships and contents.

Recovering sunken cargos was nothing new. The Spanish even tried it with their own galleons back in the 1700s. But the boom in diving technology, sonar and commercial submarines in the 1970s made deep-sea recovery more practical, though still a dangerous, expensive and frequently fruitless endeavour.

During the next three years SSA spent US$10 million of investors’ money in archive searches and sending a boat and submarine to search for the San Jose off the coast of Colombia. It seems like a lot of money, but by then the estimated value of the cargo was set at a fabulous US$10 billion. Who wouldn’t buy in?

And then it seems SSA hit the jackpot. In 1982 they filed a report to their Colombian counterparts. In this were coordinates giving the ‘immediate vicinity’ of a wreck they claimed to be the San Jose in Colombian territorial waters at a depth of 300 metres, along with details of ‘piles of timber and debris consistent with objects’. The SSA team immediately started making plans for the salvage.

Instead the US company got locked out of Cartagena harbour and locked in to three decades of court wrangling over the rights to the wreck. Immediately after being advised of the ship’s location, the government of Colombia ‘changed the rules of its agreement with SSA…offering only a 5% finder’s fee,’ said SSA, who instead turned to the law courts to fight for their original 50% stake and the right to salvage the wreck.

Robbing the pirates?

Somewhere in the Colombian government – perhaps even at presidential level – a lightbulb came on as someone realised that giving up 50% of US$10 billion dollars to a foreign company was not clever. The Colombian hierarchy had caught the same treasure fever infecting SSA and its investors. Officials were scrambled to thwart SSA by creating new laws then trying to apply them retroactively to cut their partner out of the deal.

But nothing good comes from something taken. Somewhere in the dark depths of Cerro Rico old El Tio was smiling. Over three decades the Colombian courts consistently backed SSA’s claims and rejected their own government’s, much to the fury of successive administrations who had to ignore their own courts and instead threatened any salvage attempts in Colombian waters with naval action.

For the frustrated folk at SSA it seemed the gold they were chasing was that pot at the end of the rainbow: the closer you get, the further it gets away. Then in 2015 their pot disappeared altogether when Colombia’s President Santos ordered another search for the wreck and then tweeted to the world: “GREAT news. We have found the San José galleon.” And guess what: the Colombian-lead search team ‘found’ the wreck nowhere near the SSA’s coordinates of 1982, and in deeper water (600 metres down, according to some).

Or so they say. The problem is that government will not reveal the new coordinates so no-one knows how close the wreck is to the SSA site, and given the margin of error for less accurate mapping in 1982 – before GPS systems were widely used – if in fact SSA were on the target.

What is clear from the Colombian navy and scientists who searched the new wreck site is it is the San Jose, as the markings on the cannons clearly show. Also clear is that Colombia wants the Spanish warship for itself. The culture minister recently told El Tiempo: ‘The galleon was found in our territory. It’s ours.’

Spain may not agree. In July the Spanish foreign minister reminded Colombia that the San Jose was a ‘ship of the state with sovereign immunity and classified as an undersea grave’. The Colombian foreign minister shot back: ‘Everything found in Colombian territory is Colombian.’

This position reflects Colombian laws pushed through in recent years that shipwrecks and their cargos found on the Colombian coast are the property of Colombia, based on the UN’s Law of the Sea. This makes sense from the point of view of a country whose coastline is full of foreign wrecks whose original owners might want them back. But UNESCO conventions on Underwater Cultural Heritage – which Colombia has not signed up to – gives some weight to the original ‘flag’ owners – in this case Spain – particularly in the case of warships.

Even outside of the UNESCO rules there are many legal precedents of nations retaining rights to their sunken vessels even in foreign waters, in fact Spain has successfully won cases against US-based treasure-hunting companies forced by US courts to return artefacts to Spain.

Patrimony? Or dirty money?

But would Spain contest the San Jose wreck in international courts? Probably not, judging from the recent editorial line of Spain’s El Pais which recommended ‘giving up’ the San Jose to Colombia. Behind the stricken galleon, it argued, was a ‘disappeared political structure of Catholic monarchs whose reign included Cartagena as much as Cadiz’. Colombians have as much right to the wreck as Spain.

Spain’s action, or inaction, on a claim to the San Jose might though depend on what future plans Colombia has for the wreck and cargo. Soon after his 2015 tweet President Santos declared that ‘the wreck is patrimony for all Colombians, to protect it should be the national goal’. He went on to announce plans for an international ‘dream team’ of archaeologists to supervise the excavation, cataloguing and preservation of the remains and the construction of a museum to house the artefacts in Cartagena.

This overlooks the likelihood that many artefacts originated in countries like Peru, Bolivia and even China (whose ceramics formed part of the cargo) but rather than suggesting, for example, that Inca artefacts might go back to Peru, the Colombian government has so far stated that ‘all goes to Colombia’ and the country has a team of lawyers on standby in the US to ‘defend against all possible scenarios’.

Another issue is which parts of the ship and cargo are ‘heritage’ – wherever their origin – and what constitutes ‘treasure’. The treasure would be uncut emeralds and gold ingots, for example and man-made items such as jewellery would be cultural patrimony to be preserved by the nation. But will the minted coins like those from Potosi be declared ‘treasure’ or ‘heritage’?

It is a key question in a cargo like the San Jose’s, particularly because Colombia has semi-privatised the wreck salvage and preservation by inviting companies to bid. This is because Colombia lacks the expertise for such technical work at 600 metres depths which, according the Culture Minister is ‘like going to the moon’.

But a private partner also means private investors who by Colombia’s recent laws can reclaim ‘up to 50%’ of the treasure. OK, some of this will repay the costly extraction and preservation work, but depending on the treasure trove could bring a huge profit to investors.

This sets the stage for some serious international wrangles: countries like Peru and Bolivia will be rightly furious if coins minted in their former colonial mines are sold off to profit private investors. Somewhere deep in the Potosi mine El Tio is smiling now, and rubbing his hands.

Billion dollar questions

So far the government has refused to say which company will partner with the Colombia, who the investors are and how much percentage they will get. On top of this is the billion-dollar question what items will be declared ‘treasure’ up for grabs, and since Colombia is writing its own rule books there is a fertile ground for the corruption, diversion and the plain theft of national assets which so often plagues Colombia.

President Santos may right now have the best intentions for the country and his tub-thumping over ‘Colombian patrimony for Colombia’ plays well to the home crowd. But in the wake of scandals such as Isagen, Oderbrecht and Reficar most Colombians will rightly doubt whether the money raised from the San Jose will truly benefit the country, rather than the usual Estrato-6 elite with political muscle to buy in and cash out.

Possibly the galleon will do more harm than good. Colombia’s uncompromising stance, like a child clutching its toys and shouting ‘all mine’, plays badly on the world stage when the country needs post-conflict friends and neighbours. And at home the population will quickly sour of if they suspect vast sums are siphoned off to the elite.

And the 600 human souls lost in the sinking seem largely forgotten. As their last physical connection to the realm of the living, the San Jose wreck is a grave site with all the sacredness that carries, a fact quickly forgotten in this rush for riches.

So what to do?

The UNESCO convention says the best way to preserve a wreck is to leave it be. Given the polemical history of the San Jose, the fact it is a grave site, and the probable conflicts arising from its recovery, this is surely the best option. Under the sea with the fishes it belongs to everyone and no-one.

But if Colombia does drag it up, can it counter the curse of El Tio? Perhaps.

A good start would be to clarify where the wreck is and compare the coordinates with those of SSA. If the US company was clearly off target then ‘adios’. But if they were close then compensation is in order, perhaps on a sliding scale of 1% of the treasure value for each 100 metres within a kilometre of the actual wreck.

Then agree the cultural heritage belongs to all humanity and not just Colombia. Of course Colombia should have the final say on what goes where, and parts of the ship and its workings and day-to-day items should stay integrated and on display in Cartagena. But why not give some significant artefacts back to their countries of origin? Handing back some items will gain good will and turn out cheaper than fighting legal battles in international courts.

The hardest challenge will be to reign in the voracious appetites of the investors already with the glint of gold fever in their eyes. Treasure hunting is such a risky business that offering a percentage share is the only practical way to get the job done. But the Galleon San Jose is already found, and so far untouched by looters, reducing the risks. The private percentage should also come down.

In some ways this colonial ship is a test for modern Colombia, and a tough one. In recent years the government has acted decisively to protect its interests – and those of the country – and bring some fascinating history to light. The San Jose Museum in Cartagena will be a jewel in a crown.

But from its position of strength the government now needs to be fair both at home and abroad. Otherwise El Tio, the little devil deep in the Potosi mines, will get the last laugh.