The Pacific’s troubled Tumaco

By Steve Hide

A version of this article first appeared in The City Paper in 2016

For more stories on Colombia’s Pacific see these posts:

Two motorboats race down a twisting channel towards the sea, jockeying for the best line on the corners as their motors roar. I brace myself as our pilot swings into another tight turn, we nearly catch the larger craft in front, but it breaks out of the channel and skims off over the silver sea. For a hallucinatory moment I am in an episode of Miami Vice, complete with high-revving speedboats on a sun-dappled ocean.

Stuck in the Pacific

´Get out and push, quick, everyone out, the tide is falling´ says the boat driver, but no-one moves. Now the driver is paddling around in the sea trying to find the deeper water. He tries again; ‘If you don’t all get out and push we will be stuck here for at least six hours until the next tide.’

But my daydream is short-lived as our motorboat lurches to a very quick stop. The 200-horse outboard kicks up, screaming, and flicks arcs of salty mud skywards as the driver fumbles the off-switch. The sound of lapping water slowly invades the sudden silence, then comes the murmuring from the 20-odd passengers behind me in the cramped boat. Our west is filled by rolling grey Pacific. Our east is a line of green mangrove forest. Under us the hull is stuck fast on a hidden sandbank. We are well and truly encallado. Stranded. This never happens to Don Johnson.

This news galvanises the passengers. We all clamber out and start to rock the boat, trying to swing the prow. The boat ahead of us has avoided the shallows and is now a spot on the horizon. We are on our own now, our only race with time.

Standing up to my ankles in the Pacific Ocean, a good half mile from land, is a salient reminder that this long wild coastline is hardly connected by to the rest of the country, in fact by only two roads in a thousand kilometres of jungle, mangroves and beaches. It is not just physically cut off, but culturally, and maybe emotionally too. Two roads. Just two roads. Take a map and check it out.

Not surprisingly, this forgotten edge of the country feels a bit abandoned. Ramshackle settlements built on stilts over the water seem to owe their design to Dr Seuss more than any planner. Towns like El Charco and Guapi, where I started my journey, cling to the banks like malignant water-creatures waiting for the next tsunami to wash them off. Just inland the rivers are being ripped up by illegal gold-miners, the hills sown with coca, all guarded by guerrillas and drug gangs. It is not an easy area to get in, and it might be even trickier to get out. Transport up and down the coast is slow and aquatic, with a variety of boats, canoes and small coastal freighters that crisscross a labyrinth of estuaries, rivers, tidal flats and shallow sand-banked ocean.

Bound for Tumaco

Which brings me back to our current predicament. The tide is ebbing fast and a muddy spit forms nearby where a heron stands and watches our antics to free the boat. We push, we heave, and we slip in the mud. ‘Push, all together,’ shouts the captain, and we all lean into the task until, slowly, the boat starts to shift and we wiggle it into the deeper water.

Then it starts to float off, leaving us with the alarming prospect of being left behind, but after some splashing we are all back on board, everyone grinning and laughing and briefly bonded by our short thrill. The motor coughs then roars to life and we are on our away across the wide Bay of Tumaco, heading for the coastal city of the same name.

An hour later we arrive at the crowded wharf and straight into the heart of downtown Tumaco, crowded onto a low-lying island, known for knock-down tsunami waves every few decades and a hair-raising history of violence.

Not all that history is that historical. Over a period of just one week last year 17 people were violently killed in and around the city. How does that happen? I ask a man at my table in a lunchtime cevicheria. The place is very popular so we all share tables. People here are surprisingly open to talk about the conflict, I notice, and my lunch companion is no exception.

‘Ajustando cuentas, ´ hesays. Settling scores, that insidious little phrase which hints that some or all of the dead were somehow into something bad and in that case they had it coming to them, didn’t they? Except now they are not here to defend their reputation. Or maybe ´mala suerte, ´ bad luck, he says. Some of the victims had accidentally seen something they should not have – something illegal – and paid the price. Surely in that case they are victims of ´mala gente´ – bad people – not ´bad luck´, I suggest. He shrugs: ´Bad people are bad luck.’

With that in mind I head out onto the hectic streets. For a town facing metaphorical waves of violence and then, intermittently, actual ocean waves, Tumaco seems a remarkably happy place with an exuberance reminiscent of India or Africa, and quite the antidote to Bogota’s street-worn blues.

Most of downtown is a giant market but trade takes second place to more urgent business in the cafes where dominos, cards, money and cold beers are slapped down. Crowds gather at the tables where the games are hot and bottles of aguardiente make the round.

Tumaco is surrounded by sea and shaped by the tides and you only need to walk a few blocks in any straight line to hit the water, in fact you can smell the salt and fish long before you glimpse it through the maze of wooden poles propping up large parts of the waterfront.

Sea food (and eat it)

The large tidal range – much larger than the Atlantic coast – and expanse of semi-submerged mangrove forests combine to form a nutrient-rich haven for marine life, which becomes a bewildering array of fish and shellfish dishes such as jaiba crabs cooked in coconut – encocadas – and served with patacones, which are large slabs of fried plantain. Tapao is a stew made with fish, peppers and plantains.

Ceviche is seafood cooked then marinated in lemon juice, onions and coriander (ask for the `natural` or they’ll ruin it with a massive glug of ketchup), usually based on large wild prawns, served with – you guessed it – plantains. The ceviche mixto usually comes with piangua clams, small black and rich clams which are a staple protein in the coastal communities, but also a source of income for the piangueros – usually women and kids – who spend their lives rooting around in the mangrove swamps digging them up. On the streets you can buy large greasy chunks of smoked sting-ray, a favourite mid-morning snack.

The Pearl

I wander through Tumaco from one side of the island to another. The island population is mostly Afro-Colombians, but in other parts of the coast there are mestizos and zambos (people with Afro-Colombian and indigenous heritage) and every combination in between.

On the street I am mostly ignored but in cafes and shops people want to talk and just buying a drink requires ten minutes of friendly banter. My only surprise is turning a corner I bump into a platoon of wary-eyed soldiers edging down the street, a sudden reminder that I am in Tumaco, the most troubled town. The trouble is it just doesn’t feel like it.

Late in the afternoon I wander across the city to the long concrete bridge that links Tumaco Island to Isla Del Morro, a larger but more sparsely populated island with beaches and up-market hotels. Fishing boats race in from the sea to make the harbour channel before the falling tide, their nets flapping in the breeze, and kids drop fishing lines from the bridge itself to haul in tiddlers for the frying pan. Out towards the surf-line the clam-diggers cast giant shadows on the sandflats as they walk out with the tide.

Tumaco’s tin roofs fuse in the last light of day and for a brief moment the Pearl of the Pacific is revealed in a lustrous glow, another one of Colombia’s treasures we hardly know we have. And as with any pearl, it takes a bit of mud and grit to find it.

PRACTICAL STUFF

The whole Pacific Coast is dominated by illegal armed groups, so go at your own risk. If you do go, stick to the main routes, look and act like a tourist, be careful where you take pictures or pull out your phone. Stay in busy areas and on the coast. You will probably have a great time. Do not go upriver by boat further than the main towns (Guapi, El Charco, Mosquera, Salahonda). Inland areas are no-go.

Transport

Fly in: You can fly from Bogota with Satena, there are direct flights most days Bogota – Tumaco.

Satena also fly Cali – Guapi (you can fly in to Cali with a variety of airlines).

You can also access the Pacific by bus Cali – Buenaventura (3 hours) or Pasto – Tumaco (7 hours). the latter route can be dangerous, do not go at night. Buses and micros leave from the main bus stations regularly.

Once on the coast taking the ´lancha publica´ is easy, go to the public wharf (every town has one and everyone knows where it is) and pay cash for the ticket, they usually sell them in the kiosk or at a small table. Sometimes it pays to buy the ticket the night before on popular routes, as the boats fill up. Timetables depend on tides, so check departure times when you buy the ticket.

The boats are semi-open and get wet, and very cold in the rain, so bring a waterproof jacket and wrap your valuables in plastic bags. You will get a life-jacket.

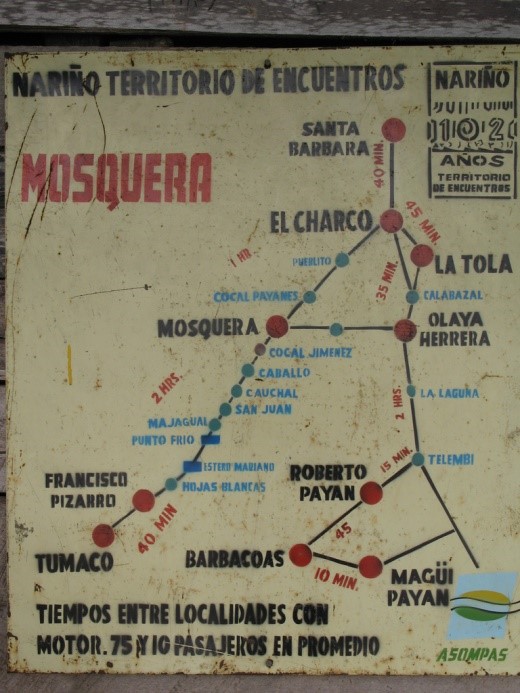

All the routes are scenic and combine sea, estuary, tidal flats, river and mangrove swamp. The route between Mosquera and El Charco, and El Charco and Guapi passes through the magnificent mangrove forests of Sanquianga National Park (officially closed but you can belt through on the lancha publica). You can snap pictures along the way.

The route Guapi -El Charco costs US$13 and takes 1.5 hours. The route El Charco – Tumaco costs US$ 26 and takes 5 hours. Normally you have to overnight in El Charco because of the tides.

Hotels: plenty of small OK hotels, no need to book. In Guapi the Hotel Rio Guapi is popular with NGO workers and tourists to Isla Gorgona, but there are other options on the same street, all about ten minutes walk from the public dock. El Charco has two or three basic hospedajes one block form the waterfront. Tumaco has a lot more options, the best around Plaza Colon. Expect to pay between US$10 and US$20 a night.

Food: cheap and plentiful, you can pig out on seafood to your hearts content. At night street stalls sell big chunks of fried fish. For the best ceviche go to the up-market cevicherias on stilts over the harbour on the entrance to Isla Del Morro, just after crossing the bridge. Make sure you ask for ´ceviche natural´to avoid the curse of the tomato ketchup. There are plenty of cheaper cevicherias down- town.