The writing’s on the wall…

This story first appeared in my Going Local column in

The Bogotá Post in 2016

Since then the conflict map of Colombia has hardly changed.

For similar posts see: ‘

The curse of plan pistola

It´s the (narco) economy stupid’

Killed in the Darien Gap

ZeroZeroZero: cocaine rules

Driving through a town on the Colombian coast I see spray-painted on the white-washed wall house are the letters AGC, which stands for the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia. Oh no, here we go again, I think; just as one of the country’s long-standing armed-group acronyms, the FARC-EP, or Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia- Ejercito Popular, is being consigned to the dustbin of history (some might say ´recycle bin´), another one has popped up to fill the territorial void and that empty space on the wall that needs to be written on with the literary equivalent of a dog peeing on a lamppost: Here I am. Watch out.

Not that the AGC is that new. It has been around for several years, and descends from a much longer line of outlaw groups ‘al margen de la ley’, as they say in Colombia. But the AGC moniker seems to be spreading, and I recently saw it sprayed in towns all along the Caribbean coast.

This marking of territory seems particularly strong in Colombia’s tangled conflicts. Over the years I have seen hundreds by different armed groups, usually on walls and roadside structures but also on cars, trucks and vans daubed with (usually) ELN or FARC after being held up at a guerrilla reten, and once, many years back, the acronym AUC – Autodefensas Unidos de Colombia – painted in the blood of its victims.

Before that, rather naively, I often wondered why this graffiti would stick around for so long. ‘Why doesn’t the owner just paint over it?’ I asked a Colombian colleague as we bought an ice-cream at a shop with FARC –EP sprayed across the front. ‘Would you?’ he shot back. He had a point. It was well known in this town that the army would patrol by day, but the guerrillas owned the night. Meanwhile the paramilitary groups were waiting in the wings to swoop in for a massacre of any supposed FARC sympathisers. This was one good reason not to have FARC-EP written on your house. But could you take the risk to take it off?

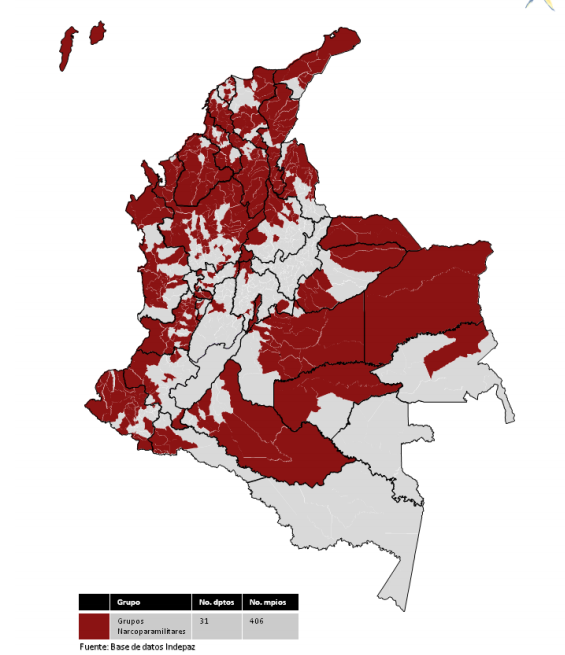

Shifting conflict boundaries

Source: Indepaz.

This brought home to me the problem facing communities in the conflict areas. There is rarely a ‘front line’ in the Colombian conflict, rather a patchwork of zones, like medieval fiefdoms lorded over by one militia or another, but with shifting boundaries and allegiances. For the settled population this poses a constant headache of who to pay off, who to proffer support, who to agree with, and whose initials to scrub off on your front wall. One mistake could be fatal.

There is also the irony that, while happy to spray-paint their presence on walls, in person the armed groups could be coy about who they actually were, and combatants could cross-dress as a ruse to see who really supports them. In one area I often passed through guerrillas would pretend to be paramilitaries, and vice-versa, and off the main roads you could stumble across a unit of Colombian army’s ‘irregular’ Contra-Guerrilla units looking like extras from Full Metal Jacket. For campesinos living here constantly being harassed for favours and information by people in camouflage with guns, it was a nightmare knowing what to say to who. This explains the general reluctance in rural Colombia for people to say anything at all.

And forget about political pigeon-holing. Readers of Isabella Allende might crave a simplified cold war scenario of swarthy freedom fighters fighting right-wing dictators, but in Colombia things are much more freewheeling with unholy alliances constantly forged and broken. In recent years the Colombian army have worked with ELN against the FARC, who themselves have forged practical and business alliances with the neo-paramilitary groups.

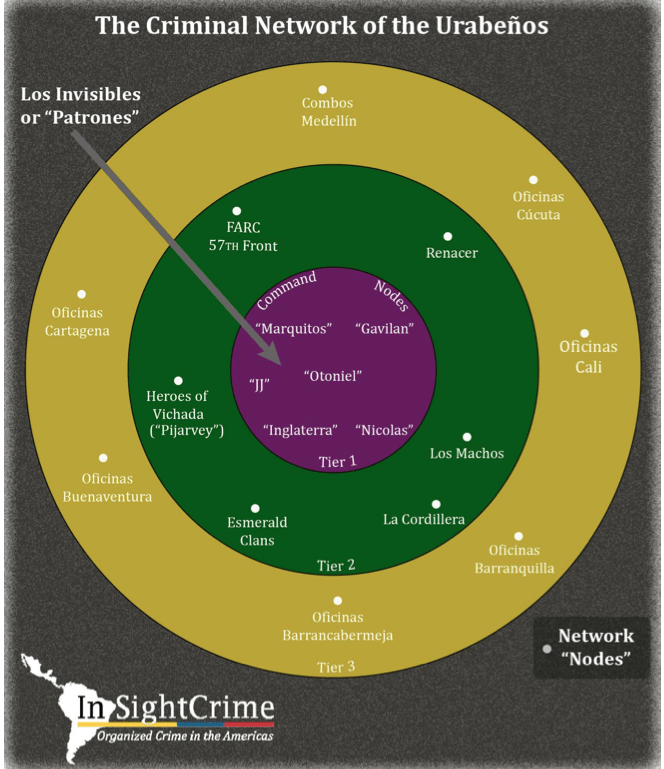

Same tiger new stripes

Perhaps this realpolitik is best summed up by the Marxist-Leninist EPL (Ejercito Popular de Liberacion), whose forces in the 1990s melted into the right-wing paramilitary groups such as the ACCU (Autodefensas Campesinas de Cordoba y Urabá), which itself grew into the nationwide para group AUC (Autodenfsas Unidos de Colombia), member of which supposedly laid down their guns in a peace process in 2004, but many reincarnated as the BACRIM (Bandas Criminales) in a nueva generacion of para-like gangs which after years of internecine wars formed the feared Urabeños which the Colombian government called the Clan Usuga (so as not to stigmatise people from the Uraba region of Colombia) then changed this to the Clan del Golfo (so as not to stigmatise the 20,000 Colombians with the name Usuga) but meanwhile the group itself rebranded as the AGC, Autodenfensas Gaitanistas de Colombia, invoking the name of the assassinated liberal leader Jorge Eliécer Gaitan, and now according to their website do social work helping `old people and mothers in the community’.

So hopefully that’s clear. But in case you were worried the original EPL was defunct, it has now popped up like a bad penny in the north-east of Colombia where it organises cocaine production in Norte de Santander. Meanwhile the AGC is trying to inhabit areas left by the FARC, and not just the physical spaces – vast areas of jungle and mountains where state presence is limited – but the political landscape and ‘fighting for social justice’ according to their communiques.

A second ‘demobilisation’?

In fact much of their literature parrots the left-wing guerrilla groups, and they end their communiques ´From the Mountains of Colombia’, the favoured sign-off of the FARC and ELN, and they are now organised into frentes, bloques and an Estado Mayor with uniformed troops complete with epaulettes. And of course the AGC wants its own peace process, something until now the government has (until now) roundly rejected and most Colombians would find hard to stomach based on the groups reputation for drug trafficking, extortion rackets, assassinating campesinos, land rights and community leaders, and the fact that many of the combatants already ‘demobilised’ once before.

This was the massive demobilisation of the AUC paramilitary forces in 2004, widely seen in hindsight as a sham with drug barons ‘buying’ posts as AUC commanders to win reduced sentences (while some of the genuine commanders were shipped off to jails in the US to muzzle their links to politicians), and groups of farmers paid to pose combatants and old rusty pistols and shotguns turned in while the real weapons were syphoned off back to the drug gangs.

Perhaps ironically the AGC blames this ´failed demobilisation’ from 12 years ago on their current existence: rank and file paramilitaries who laid down their guns were then ruthlessly killed off by death squads forcing the survivors into the arms of the drug gangs.

There is a grain of truth in this. The murder rate in Cordoba, the home of many ex-paramilitaries, went through the roof in the years after the AUC was disbanded in 2004. Dark forces were ‘killing of any living links between the paras and the politicians’, someone who lived in Monteria told me at the time. If this is true then maybe some former AUC were forced to take up arms again in a similar way that many FARC guerrillas joined the ranks to escape persecution, a survival strategy rather than a call to criminality.

Uncertain future.

This is a core claim by the current AGC: many demobilised paramilitaries were assassinated or unable to go back to their homes, the hidden reality being that the ‘state with its costly security apparatus are incapable to give the necessary protection… to the demobilised’. It is certainly an alarm call for the current peace process, and imminent demobilisation, of the FARC, many of whose guerrillas have already filtered into the ranks of the AGC rather than face the uncertain future of life with no guns.

– Ejercito del Pueblo, the ‘People’s Army’

Meanwhile the Colombian government refuses to accept them as anything but a criminal gang, insisting to call them Clan del Golfo after their cradle in the Gulf of Uraba, on Colombia’s Caribbean coast. This clearly riles the AGC who point out – perhaps counterproductively – that their ‘activities’ extend far beyond the coast, and they have used the initials AGC since 2008. ´We are weary of the creative titles…we are and will continue to be the Autodefensas Gaitanistas de Colombia’ they write in one editorial entitled ‘What’s in a Name?’.

It is unlikely the neo-paramilitary group will smell sweeter with the acronym AGC, but it might bestow a thin veneer of political objective to their existence. Which is of course why the government refuses to use it, added to a reluctance to besmirch the name of Eliécer Gaitan, one of Colombia’s most revered political fathers.

In Colombia though things can change. Recent rumours suggest the state is in secret talks with the AGC, Urabeños, Clan Usuga or Clan del Golfo, however you choose to call them. The first official sign might be wider recognition of the acronym AGC. For now, the writings on the wall.