Tierradentro: journey to the heartland

by Steve Hide

A version of this story appeared in The City Paper in 2015

For posts on similar road journeys see

– Armero on my mind

– Boyacá backroads to El Cocuy

I am on a journey to Tierradentro, an archeological site of underground burial chambers scattered over a swathe of steep green Andes. These painted caverns were dug by a long-forgotten people into the volcanic rock on ridges and small plateaus on some of the most spectacular Colombian mountain scenery. But Tierradentro, literally the inner land, has a much richer back-story than just a tomb with a view. It sits deep in the contested mountain reserves of the Colombia´s Paez Indians and still pulses with the resistance that took root 500 years ago when the conquistadors first stumbled their horses over its rocky riverbeds in their search for riches. And driving there across the mountains from Cali is going to be huge fun. But which way to go? Maps show several routes west to east across the Central Cordillera. Maybe the internet can help.

A tomb with a view. The scenery of Tierradentro, literally the ‘inner land’.

Driving into danger…

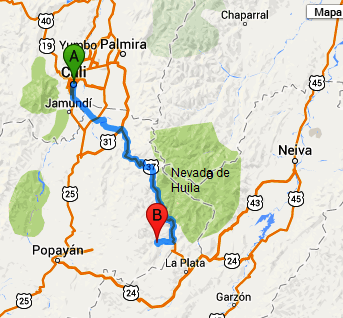

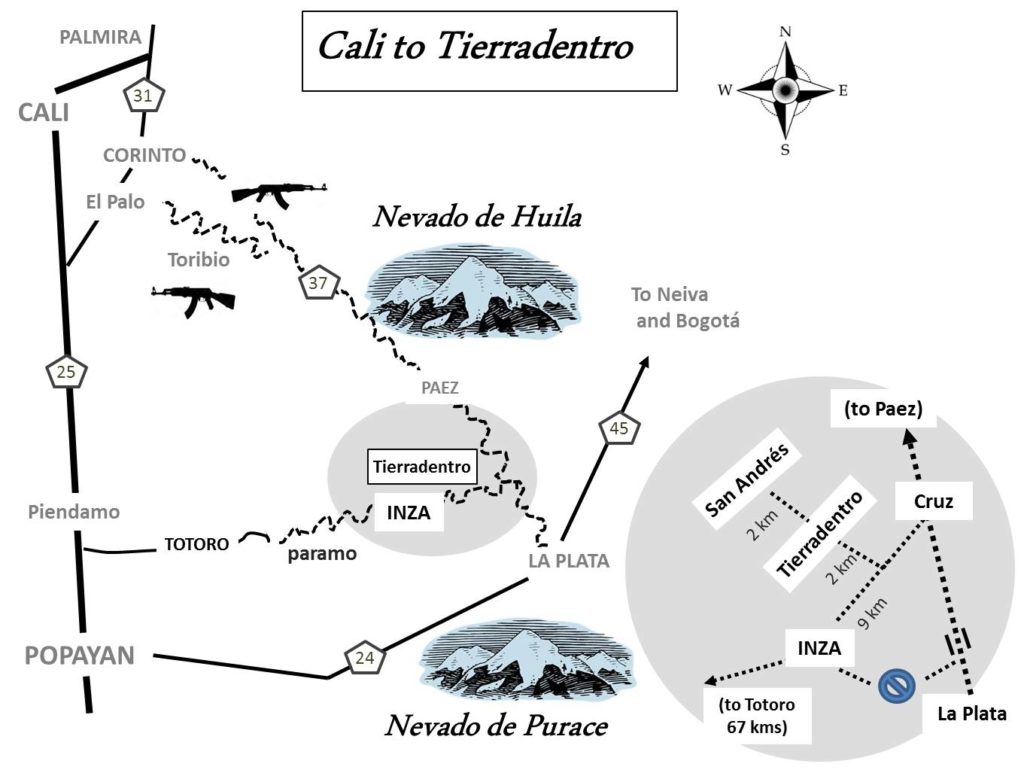

A quick google throws up several websites with digital maps, with ´LasDistancia.com´ also giving a 28-step detailed set of instructions: ´Turn Left at Carrera 3´ etc all the way along Route 37, a mountain road which runs east along the skirts of the volcano Nevado de Huila, past the towns of Toribio and Paez, all the way to the Tierradentro, in total ‘202 kms and 4 hours 40 minutes drive´. I double check on INVIAS, the Colombian road authority website website with its Viajero Seguro(Safe Traveler) maps. It shows the same route along Route 37 . So we set off early next morning driving east across the misty Cauca valley. The closing mountain range, silhouetted by the rising sun, rises over the misty cane fields like a giant cardboard cutout. What can go wrong?

We sit down in a small café. The owner gives us coffee, corn-bread and eggs all served with a big smile. A local strolls across the road to the cafe. He is in green shorts, a short woollen poncho and a camouflage cap with a Che Guevara sticker. I get the feeling he is coming to see us. ‘Do you like Che Guevara?,’ I ask him as way of opening the conversation and also to assess if his cap logo is a fashion statement or something more political (because with El Che it can go either way). ´Yes, I like him, very much,´ he replies. I explain our planned route and he shakes his head. ´You cannot travel this way through the mountains, the road is very long and slow. You will find it… inconvenient. Best to take a different way.´

We stop at El Palo, a small town on the edge of the cordillera and gateway to Route 37, that should take us into the mountains close to a town called Toribio. The local road-signs are spray-painted with ´FARC-EP …present´, the calling card of Colombia´s largest guerrilla group. This doesn’t look good. A soldier is standing on the street corner street. We ask him how to get to the turn-off. ´Don´t know, ask a local,´ he says. He seems a little nervous. We see a foot patrol moving up the street, equally alert.

A file of soldiers pass by the café, but our new friend does not even glance up. Then woomph there is a loud explosion from the hillside behind. ´Are they blasting the road,’ I ask, hoping it might just be dynamite to clear rocks. ´No, ´ he says calmly. ´There is fighting´. He suggests another route that runs across the mountains from further south down the main road towards the city of Popayan.

So we finish breakfast and drive off south the road running parallel to Andes, with the mountains now seeming more impenetrable than ever, passing army checkpoints, armoured cars and more ´FARC present´ graffiti. Our carefully-printed Google maps flutter uselessly on the dashboard.

´Bloody Google,´ I moan. ‘You would think they would know better than to send us into a war zone.’ We are stuck on the main highway now, battling double-over-taking buses and thundering trucks all hell-bent to get to Popayan before us. Several times we are forced onto the berm and nearly into the ditch. I begin to ponder if this mad traffic, clearly a known risk, is more or less dangerous than the known unknowns of the mountain route (landslides, blockages, crumbling roads), and where do the army and guerrillas fit in on the risk scale? Are they unknowns that we think we know? Or knowns that we don’t know? Or even unknowns that we don´t even think we know? Mentally I am entering deep Donald Rumsfeld territory.

The high mountain road

Our luck changes an hour later with a road-sign marking a small road east into the mountains to ´Totoro, Inza and Tierradentro´. This was both welcome and unexpected as this route had yet to be highlighted on the internet maps, but a large touristy sign for the ´Parque Arqueologico´ looks promising. A perfect tarmac road climbs steadily to Totoro, a small town in full flush of Saturday market which takes on an almost medieval aspect with pigs roasting on the spit and local staggering around the streets after their lunchtime tipple. No-one pays us any mind – they are too drunk to notice – and we drive slowly through the merry throng, then up and out into the high meadows and Andean moorland that forms the roof of the cordillera.

The next three hours is on a road as lonely and beautiful as any I have seen in Colombia as we pass field of wild flowers with grazing horses and tin-roof farmsteads, kids scampering in the yard. There is just one small village along the way – Gabriel Lopez – three cars and a potato truck. In places the road is new and engineered to perfection, only marred by the ´FARC-EP´ graffiti, the guerrillas spraying their presence like randy tomcats on the concrete road snaking into their territory.

At around 3,500 metres high we enter a wild paramo plain covered in stunted trees and frailejones plants and then down curve after curve of perfect concrete road. Since there are no other cars, I can swing wide on approach, ride the camber down, cut across the inside curve, gently slow on the gears ready for the next curve as the waterfalls tumble down the rain-forest cliffs to the valley below. Never mind ancient tombs, this is car heaven.

But soon we are back down to earth, or rather sticky mud, and plugging our way through boulder-strewn landslides. Then as we approach Inza we heavy machinery clearing the road, the crews wave and smile as we pass.

The lush valley of Tierradentro

Now we can see the town sprawled on a hillside overlooking a vast green landscape of valleys, buttes, cliffs and peaks, with a ribbon of dirt road connecting villages and, somewhere down there, the archaeological park.

The park surrounds a visitor center and museum set in a lush valley half an hour´s drive from Inza. The tombs are scattered over nearby hillsides, which means walking or horseback, and you can wander over the trails as you please in your own time, crossing the small streams that wind through wooded hills, trees boughs laden with bromeliads and orchids and host to squadrons of chirping birds that dart around your head like extras from Bambi. There are hardly any other tourists and, best of all, no gift shop.

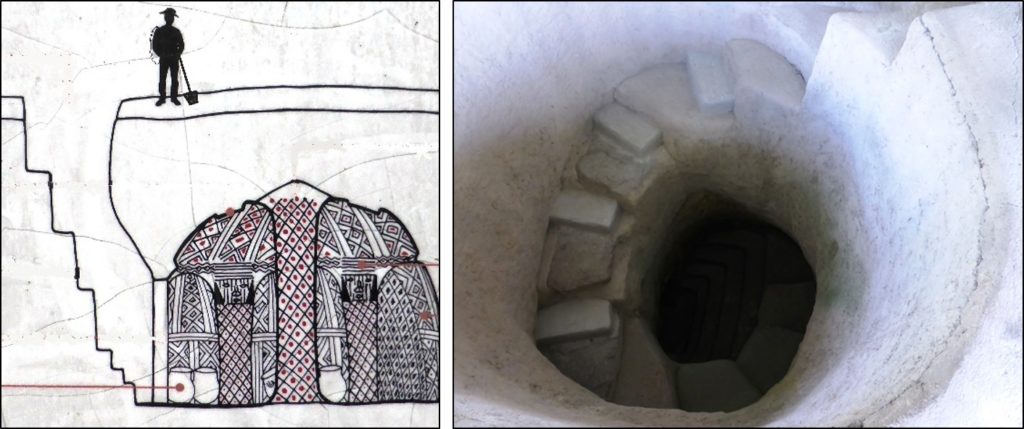

We walk up a steep track to the Altos de Segovia, where the best-preserved tombs are said to be. The site is a series of tin-roofed huts on a small grassy plateau. The tombs lie beneath. Two very laid-back Paez guard with a large bunch of keys, opens the trapdoors that lead down into the bowels of the earth. It looks dark down there. ´Don´t worry,´ says the guard, ´the lights will come on automatically.´

The burial chambers are as you might expect: dank gloomy and claustrophobic, with arches and pillars, some with simple carvings and geometric paintings. It is the steps down that catch my attention, hewn from the rock with the abandoned flair of a Dr Seuss cartoon. There are no handrails and a good drop into the chamber if you miss your footing. ´Has anyone ever fallen into the tomb?´ I shout up to the guard. ´Only when we throw them in head first,´ he laughs. This is the kind of tour guide I can relate to.

That night we stroll up the hill to the village of San Andres, a small settlement with an historic church and a few restaurants and guest houses. There are no other tourists in view and the restaurant closes early. I ask the owner why the lack of visitors – it is a bank holiday weekend – but he does not seem too bothered. ´A few people come every day but not that many. It will get busier at the end of the year´.

Back at the guest lodge the manager is equally sanguine about lack of people rushing to Tierradentro. ´It is not really on any main routes,´ he suggests. He can say that again. I ask him about the route 37 further north, through Paez and Toribio back to Cali. He frowns. ‘This is a very dangerous road. The armed groups there are muy bravos´. Very fierce. Two mountainbikers were murdered there earlier in the year, and two tourists traveling through Colombia had their large motorbikes stolen and were left to walk out.

I ask him about the FARC graffiti on the road we took from Totoro to Inza. ´The guerrillas there are not too interested in bothering tourists along that road, though they did burn four bulldozers of the road-building company for not paying the vacuna.’. The vacuna is literally ´vaccination´, money charged by the FARC to companies working in their territory.

A troubled land

In recent years there has been friction between the indigenous Paez people and campesinos (peasants) in the area, he explains. ´The Paez are reclaiming their ancestral land and in some cases burning the farms of the campesinos. It´s a bit hard on the peasants since they have been farming the area for many generations, it´s not like they just showed up yesterday.´

NOTE 2019: this article was written in 2014 before the peace process with the FARC. However, the Paez people are still facing discrimination, land grabs and attacks from illegal armed groups and state forces. The archaeological site and main access routes should be safe for visitors. But the region still remains tense and if you plan to travel deeper into the mountains check carefully in Tierradentro on the current situation.

And sitting up in the mountain heights in the fortress-like mountains are the FARC’s 6th Front. But if the FARC ever had any noble intentions to defend indigenous rights it soon got subsumed in the day-to-day business of extortion and drug running through the strategic mountain passes that link Colombia’s vast interior with the Pacific coast. The war on drugs brings the modern Colombian army into the mix. Game on.

´The guerrillas like to think they are helping the Indians,´ says our host. ´Maybe for a while they did. But that´s changed, and it´s not easy to ask people with guns to pack up and leave.´. Making it more complicated is the fact that most of the FARC in the area are actually Paez indians, so the guerrilla movement has ended up dividing the host community, a fracture line willingly exploited by a Colombian state also trying to win hearts and minds through the barrel of a gun.

To achieve some balance, the Paez traditional leaders have an equally tough track record of chasing the Colombian army out their territory as they do towards the guerrillas, with video footage put online in recent years of stick-wielding community guards rounding on armed soldiers.

Our hostel manager sums it up nicely: ‘remember the guerrilla movement has been fighting the state for 50 years, but the Paez have been resisting everyone for 500 years´.

The next day this local conflict explodes onto the pages of the world press: a policeman has been shot in Torobio, fighting escalates in the high mountains, culminating in the murder of two Paez community guards by the FARC 6th Front. The Paez community is in uproar, demands demilitarisation of their territory, capture the FARC guerrillas responsible (their own teenage sons) and condemn them under their own community-based legal code to decades in jail. The FARC, clearly stung by what they see as betrayal, issues a communique on its website by declaring its parallel goals to that parallel those of the indigenous (state resistance), but then declares some Paez civilian leaders as ´legitimate military targets´ and in at least one version of the threat ends up ends with an absurd insult you might hear in a school playground: ´we are not playing with you toads any more´.

I reflect on all this driving back over the lonely road to Totoro. Unless someone told you, it would be hard to guess at the turmoil in this part of the country. Like with the tombs buried below, there is always something new to be uncovered in Colombia, and not always something you might want to find. I breathe a small sigh of relief when back on the main road. Even the trucks seem friendlier now.

Practical information

Tierradentro itself can be considered safe to visit, but do check local news reports first for conflict in the area around, and pick your route carefully….! Most travelers reach Tierradentro from Bogota or Popayan via La Plata. The we took from Cali is less travelled, but here the details:

Total distance 216 kms. In November 2014, journey can take 5 to 7 hours depending on road conditions (and delays for roadworks). When new Totora – Inza road is paved (work ongoing) the route will be very fast.

· From Cali take the main highway Route 25 south (towards Popayan).

· 117kms south of Cali (about 15kms N of Popayan), turn east onto the paved road to Totoro, Inza and Tierradentro. The junction is well signposted. You can buy fuel and food in Totoro and Inza.

· Kilometre markings from the main road are:

Km 22, town of Totoro (good paved road)

Km 40, village of Gabriel Lopez (mixed paved road and dirt road)

Km 50, Paramo de Las Guanacas (good paved road, highest point of road).

Km 89 town of Inza (roadworks, landslides, road can get blocked).

Km 98 T-junction, turn left (north) here. Well signposted. Good dirt road.

Km 100 Tierradentro archeological site. Hostels and restuarants here.

Km 102 San Andres, village with historic church and more hostels etc.

Entrance to the Archeological Park is 20,000 COP for two days, including museums. There are plenty of small cheap hotels and hostels within walking distance of the site. Bring sun and rain protection, good walking shoes. Most people allow two days to enjoy the sites without being rushed.