Venezuelans on the road in Colombia

Venezuelans on the road: migrants seek freedom and food.

posted in February 2019

Colombia’s roads are full of Venezuelans. Like the Okie’s trekking west after the dust-bowl disaster of the Great Depression in the 1920s, these impoverished migrants are fleeing a man-made crisis, in this case the economic collapse of their home country.

Back home, hyper inflation – 1,000,000% – has rendered Venezuela’s currency, the bolivar, worthless. Venezuelans have lost their life savings.

Now they trade their worldly possessions to get basics to survive, or to travel to Colombia, the nearest country. For many the motive to leave home is hunger and lack of medical supplies in Venezuela, where children are dying from lack of basic supplies. In Venezuela itself the illegal government is shored up by state forces and irregular armed gangs that murder and maim. The general population is living in fear and danger. For some escaping to Colombia is their only chance to survive.

But Colombia is no paradise for them. Sure, there are things in the shops, but there is no work and little money. But Colombia is no paradise for them. Sure, there are things in the shops, but there is no work and little money.

See my related post Venezuelans in Bogotá

In 2018 I visited to the border areas with donated food, soap and clothes in my car. I talked to many migrants, gave many rides to the next town. Here are some photos and stories of their desperate situation, some of it previously appeared in background information published in The Bogotá Post as part of its extensive coverage of the crisis.

How you can help desperate migrants

Please share this post. The world needs to know about the suffering in Venezuela, and the plight of the migrants.

While researching the Venezuelan crisis, and contributing to the stories in The Bogotá Post, above, I encountered a migrant family in Riohacha whose story is covered here. In late 2018 I set up a fund here:

GoFundMe page ‘Desperate Family Needs Our Help’.

We have raised money for them, but very sadly Rosangela, the mother of Geomar Junior, died in January 2018, from medical complications. I am still raising money for Geomar Junior and his dad, so please contribute if you can, or share via social media.

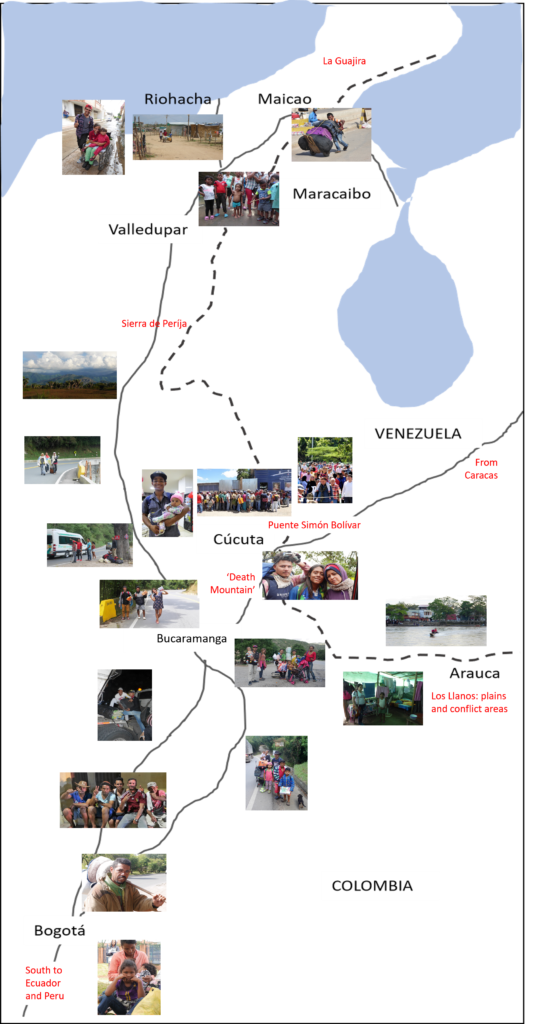

The Route

Thousands of migrants are on the road in Colombia. Many are heading south to Bogotá and on to Ecuador and Peru.

Migrants typically enter leave Venezuela close to the Colombian border towns of Maicao, Valledupar, Cúcuta or Arauca.

But with political tension rising many official border posts are closed, so migrants are more often crossing in remote areas, such as the sea route to La Guajira, or the mountains of Sierra de Períja, or across the the rivers of the Llanos, the eastern plains.

Many migrants stay close to the borders to keep in touch with family – old one and young ones – back in Venezuela. This has lead to much crowding and crisis in the Colombian border cities.

Others move away to find opportunities in other parts.

Cúcuta to Bogotá is 650 kms, or 16 hours by car, over mountains. Or ten days walking.

Maicao to Bogotá is 1,100 kms and 20 hours by car, over flatter roads but in extreme tropical heat.

In September 2018 I visited Arauca, Cúcuta, Maicao and Riohacha as part of an assessment for a health NGO. And in October 2018 I drove the whole route from Bogotá to Riohacha, meeting many migrants along the way.

I was staggered by the vast numbers of Venezuelans both trying to settle, and those moving to find some chance of work and income. On an average journey of one hour I would pass hundreds of migrants, often in small groups, some walking, some hoping for rides. And many families with children.

Many people I talked to had come from stable jobs and homes in Venezuela. They were not used to begging or life on the road.

I was also amazed by the generosity of the Colombian who help their neighbours. While some politicians and right-wing evangelical churches have tried to whip up animosity towards the migrants, many Colombian continue to help them. Perhaps they remember that in decades of conflict in Colombia, Venezuela took in millions of displaced Colombians.

The Crossing

Colombia and Venezuela 2,200 kilometres of porous borders crossing deserts, mountains, swamps and jungles. There are only a handful of official crossings and some are now closed. But there are thousands of unofficial ones, called ‘trochas’ – tracks.

Neither country has ever controlled the frontier which has for decades been a smuggler’s paradise for contraband, drugs, arms and petrol. Now the main traffic is human.

The border areas are conflict zones controlled by ruthless armed gangs who in some cases extort the migrants. Crossing is not easy. Many migrants disappear.

Colombia has little choice but to let them in, as much of the border is defined by geographical barriers, such as the Sierra de Perija, rugged hills which the migrants cross on foot, or the swampy plains of the Llanos in Arauca.

More than 1.2 million Venezuelans are thought to have entered Colombia in recent years. Many more move on to Ecuador and Peru. Many more flit back and forth across the border looking for food and medicine that is non-existent in their homeland.

The search

Once in Colombia, most Venezuelans are ‘informal migrants’. Very few have passports, which are hard to get in Venezuela and available only to the wealthy. So far the international community has condemned the ‘illegal’ Maduro regime in Caracas, and criticised the violent human rights abuses there, but refuses to recognise Venezuelans fleeing as ‘refugees’.

This paradox leaves Venezuelans are vulnerable to abuse, exploitation, slave labour and forced return to Venezuela, where they are even more at risk. Many migrants join ‘la rebusca’, the search for a means to survive. Many beg, sell sweets, rely on the help from small NGOs, the church, and the kindness of Colombians. Many humble Colombians do help the Venezuelans with food, clothes and cash. Truckies give rides. As John Steinbeck wrote about the Okies in his classic book The Grapes of Wrath: ‘when you’re on the road, it’s the poor that will help you’.

The journey