Will Colombia cull its cocaine hippos?

Colombia could now be home to 200 wild hippos, according to a scientific report which also proposes controlled hunting of the African mammals which originally escaped from drug baron Pablo Escobar’s ranch in the 1990s.

This story also appeared in The Bogota Post in April 2023.

See related posts: Pablo Escobar’s Hacienda Naples; The Giant Sloth Slaughter

At current breeding rates, Colombia’s hippos could exceed 1,000 in another decade. The renegade semi aquatic mammals need urgent reduction, says a report on the management, control and eradication of Hippopotamus amphibius co-written by the Humboldt Institute and National University.

According to El Espectador, “Scientists recognize the negative impacts they can have on the ecosystems they have been colonizing… invasive species are one of the main drivers of biodiversity loss not only in the country, but in the world.”

Culling is just one potential control method. Confinement and moving them overseas has also been mooted with recent announcements of hippo relocation to places like India and Mexico.

Imported intentionally and illegally

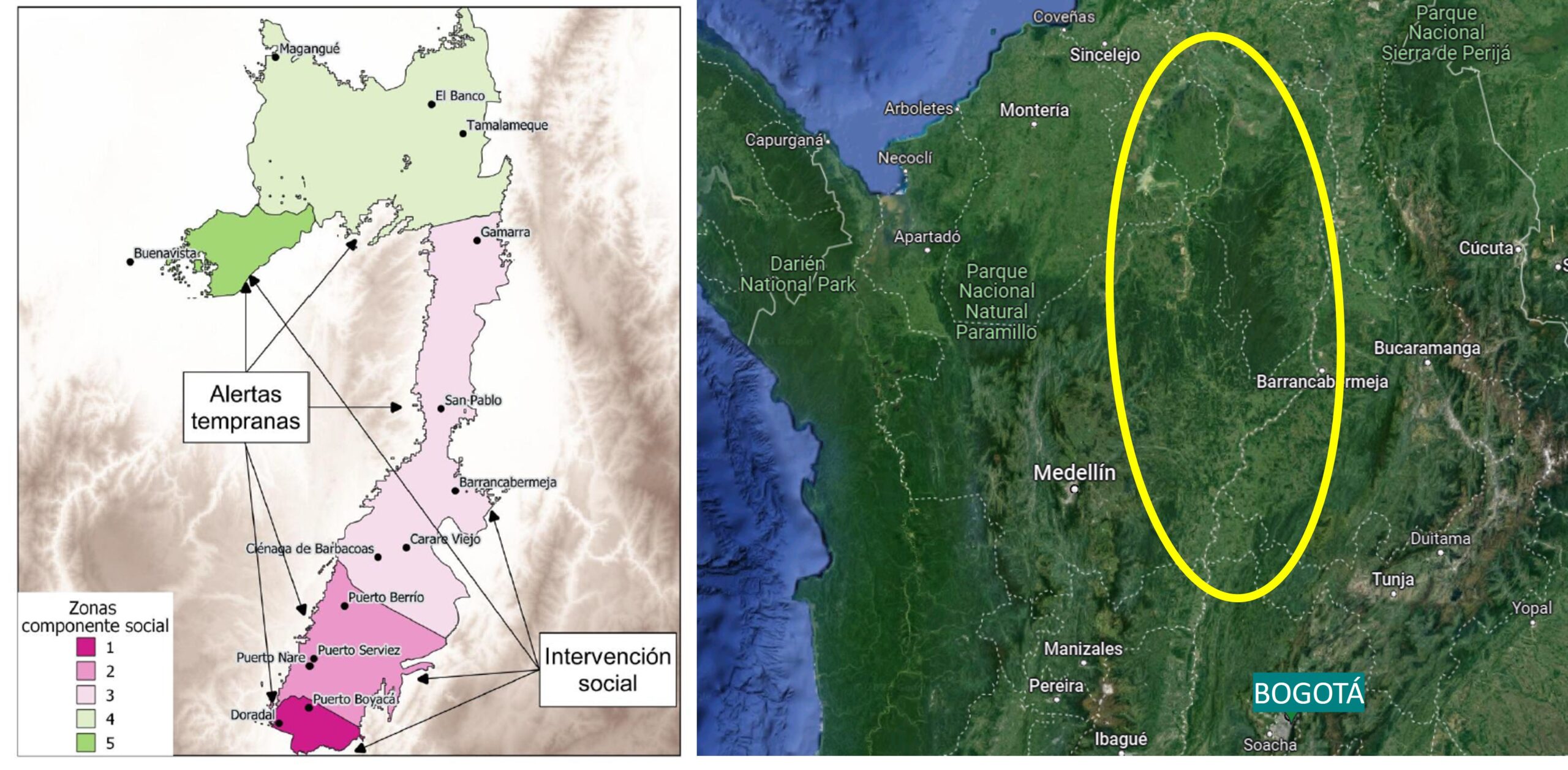

Meanwhile Colombia’s cocaine hippos march on in the “ideal conditions” of the Magdalena River. The 170-page study, which is yet to be validated by the Ministry of the Environment, details the expansion of hippos into seven population groups around Nare, Berrío, Yondó and the Momposian zones of the lowland Colombia, an area covering 100 kilometers of river and swamps.

According to the report, the hippos are descended from three breeding pairs introduced to Colombia “in an illegal and intentional manner in the 1980s” by Escobar and kept at his ranch Hacienda Nápoles, where some captive hippos are still on display today. Their wild cousins escaped soon after Escobar’s death in 1993 when the ranch fell into ruin.

Last year, a survey registered 169 free-living hippos though it’s a sub-count: an upper estimate suggests as many as 215 individuals could be out there. The majority are calves and young adults looking for new territories.

The largest group – around 117 at the last tally – still wallows in lakes and rivers close to Nápoles in Puerto Triunfo, Antioquia, the area most affected by the hippo invasion. Just last week a hippo was killed and two people injured when their car struck the massive mammal on a main road in nearby Doradal.

“This painful accident reaffirms the importance of urgently carrying out the translocation of hippos to India and Mexico,” said the Antioquia’s governor after the accident, asking for government support for the plan which could reduce the local hippo population by 70 beasts.

Competition for resources

Crashing into them is just one of many social and environmental problems connected to the invaders. Competition for resources, displacement, disease transmission, contribution of large amounts of fecal matter that overloads river systems, soil compaction, are some of the other impacts we’re seeing.

Hippos eat land vegetation – up to 50 kilograms a day – but poop it out in the water. This raises nitrate levels, causing algal blooms and killing fish. Their large bulk can erode riverbanks and destroy the local environment, according to the report. That said, it’s not clear how much worse this is compared to widespread cattle farming in the region.

Another potential impact is on existing native semi-aquatic mammals such as manatees, otters and capybaras, though these were heavily under threat even before hippos. Then there’s human-hippo interactions with wild hippos wandering through towns and villages around Puerto Triunfo and reports of confrontations with fishermen and farmers.

It’s not as fun as it sounds: Hippos are aggressive and territorial and officially the deadliest large mammal – they kill on average 500 people in Africa every year – and can attack boats and canoes and people on land, and have been known to attack humans, cattle and horses around the River Magdalena.

The demise of Pepe

Despite these dangers though, many Colombians welcome them, and the report admits hippo support among local folk who see the animal outlaws as “Pablo’s pets” and tokens of the “opulence and prestige” that the notorious cartel leader formerly brought to the zone, along with danger and destruction.

Even the odd rogue hippo has its fans. In 2007 local environment authorities were stuck with the case of a male hippo called Pepe which attacked canoes and broke farm fences close to Puerto Berrio.

Plans were made to trap it and transfer it to a zoo in Costa Rica but permits fell through so after continued aggression by the hippo, it was shot by trained hunters in 2009.

Then controversy erupted after photos circulated of army troops posing with the dead Pepe, who was still clearly popular with some of the local population. This sparked a court ruling protecting other hippos from being hunted.

Pepe’s historical case highlights the tightrope currently walked by environmental agencies in the Magdalena Valley: addressing the hippo problem in ways acceptable to a human population often campaigning to “leave them in peace”.

Of course, some local people like hippos for other reasons. According to the report, some have ended up grilled on the barbecue and baby hippos have vanished into the exotic pet trade or even been adopted as pets by local families.

One clear conclusion of the Humboldt Institute and National University study is that Colombia needs less hippos. And this is done best by “controlled hunting, translocation and confinement.” Previous attempts to sterilize hippos were not seen as a realistic way forward.

And as we’ve seen with the case of Pepe, flying hippos overseas is also a difficult option. If they can’t transfer one hippo, how will they manage seventy? India and Mexico might want hippos, but can Colombia deliver?

Confinement could mean creation of a “hippo game park” or large cages somehow controlling them with physical barriers to keep them in which is very challenging given their size, strength and ability to walk underwater.

Rights for hippos

What’s left? Culling Colombia’s cocaine hippos either through hunting or possibly poisoning them, activities which are bound to create controversy, court cases and international scrutiny. The Ministry of the Environment has yet to pronounce on the Humboldt Institute and National University study but will likely find itself in a legal battle as soon as it does.

Crucial to any hippo control is the court ruling in 2022 that hippos are “invasive species” in Colombia, but already that legal framework is being challenged at State Council level by private citizens arguing that animal welfare regulations should supersede any kill or contain orders.

According to this challenge hippos are “sensitive exotic vertebrate beings” and “their welfare must be observed in any management plan”. That probably excludes killing them.

And by some legal twist, Colombia’s cocaine hippos are “protected persons” under US law after a nutty ruling in an Ohio courthouse in 2021, though it has no legal bearing on Colombia.

More human-hippo accidents, such as last week’s crash in Doradal, could swing the pendulum. Following news of the dead hippo and injured humans, the Attorney General’s Office reminded the State Council that “keeping Hipopotamus amphibius on the list of invasive species in Colombia is crucial to address the environmental crisis generated and protect the life of the community.”

Still, a strong sector of the public will hold out for the hippos. It will be a long road to eradication. For now, at least, Colombia’s hippos can rest easy in the Magdalena River.